Sir Clive Sinclair is one of the two most directly influential people in my life who I never met. He created the UK’s first mass-market home computers, among other inventions. I found the ZX81 and ZX Spectrum endlessly fascinating and taught myself to code (BASIC and Z80, in case you’re interested), leading to a degree in computer science and a lifelong love of coding.

The other is Nobel laureate Geoffrey Hinton, often called the “godfather of AI”. His 1986 paper, “Learning representations by back-propagating errors”, with David Rumelhart and Ronald Williams, started my fascination with AI and neural networks. My university project in 1991 was a neural network system based on that paper; my classmates thought I was crazy but it led directly to my career in data and AI, which has lasted for more than 30 years now.

Professor Hinton’s seminal paper cites only four papers, and one of those is “Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition”, written by the same three authors. It is a self-citation.

At Times Higher Education we sometimes hear that we should remove all self-citations when measuring research quality for universities globally. But that is far too simplistic an approach.

The question is: was that self-citation from Hinton, Rumelhart and Williams a reasonable citation? I would argue it was. Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Neils Bohr, Richard Feynman, James Watson and Francis Crick, and Stephen Hawking all self-cited too; again, given their groundbreaking discoveries, it’s difficult to argue that these aren’t reasonable citations. In fact, high rates of self-citation are typically associated with unusually influential authors who have published widely, according to a recent paper.

Of course, this isn’t to say that all self-citations are worthy. There are definitely some opportunistic self-citations in research papers; equally, there are examples of groups of authors citing each other solely for the purpose of increasing their number of citations. There is evidence of attempts to game bibliometric data in parts of the world, usually for personal rather than institutional gain.

So how can we address situations where there is inappropriate behaviour, while recognising the complexity of the world of academic publishing?

In our assessments we remain vigilant and frequently review our metrics to discourage perverse incentives and to avoid rewarding bad practice where we can. Our partners at Elsevier review the quality of journals and will suspend journals where malpractice is suspected, such as pay-to-publish publications; the research in these journals is not considered in any of our research metrics.

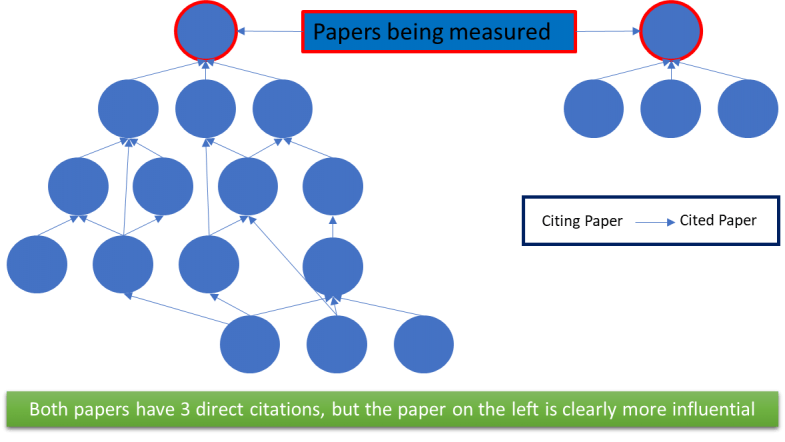

As a key part of this, two years ago our principal data scientist, Billy Wong, created a measure we call Research Influence. This doesn’t just look at direct citations, but how the papers that cite a paper are cited themselves, and recursively onwards. There is a combinatorial complexity to this, so Billy utilised a version of the PageRank iterative algorithm (used originally by Google search) to identify influential papers, and at the same time weed out papers that had no influence in their respective fields.

The diagram below illustrates this, with both papers being measured having three direct citations, but the paper on the left clearly being more influential in its field.

We have conducted analysis on a sample of papers to test the validity of this research influence approach and we can see that well-respected papers score highly; also, groups of authors who cite each other, but are not cited by others, have papers with very low research influence scores. And to reinforce my original point, some very influential research papers are cited by the authors themselves in subsequent work.

We are always conducting research and analysis to find ways to improve our rankings. For instance, we are currently reviewing our research quality metrics to determine whether we can present a more balanced view by adjusting their weights. We also continually look at finding ways to identify and rectify issues in data we receive, such as our recent work on detecting a voting syndicate in our reputation survey. Without this ongoing work, we realise our rankings would become unfit for purpose, and be nowhere in the thoughts of universities, students, academics, governments and employers.

And where would I be without Sir Clive and Nobel laureate Hinton? I dread to think.

David Watkins is managing director of data at Times Higher Education.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?