I nervously paced on the mildewed green carpet, my body involuntarily quivering and my tummy feeling like it was trying to escape. My first client was about to arrive. The seemingly endless Scottish rain was leaking though the window seams in my dank Leith basement flat, and mould crept across the ceiling. “What the hell am I doing?” I thought. But it happened, and it paid for my food that night: the best meal I’d eaten in a while. It paid for a few days’ meals, actually.

So one client became two, three, four. And between my encounters with them, I read books and wrote my university assignments.

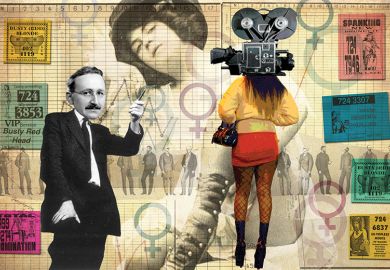

My story is not special or unique. A large and apparently growing number of students in the UK are turning to sex work. Gaining accurate figures is impossible. Studies suggest that between 5 per cent and 10 per cent of the student population may be involved in sex work, but the real number is almost certainly higher, since sex workers often do not wish to disclose what they do. Student sex workers in particular have a very justified fear not only of stigma, marginalisation and verbal and physical abuse, but also of university expulsion, deportation (if they are international students) and possible criminalisation – all of which would undermine the very future that they are studying and working so hard to gain.

The red umbrella is the international symbol for sex workers’ rights, and the umbrella is wide. A student sex worker may be a 19-year-old offering sex for cash. But they may also be a 43-year-old single mother on benefits with two young children, studying part-time to be a social worker and offering erotic massages in her spare room. They could be a 24-year-old man of Turkish background who struggles with international fees and sells sex from the streets on weekends. Or they may be a young trans woman early in her transition who, because of stigma or a lack of confidence, cannot get a public-facing job and so does sex-cam work in the evenings.

In my case, I escorted in between a six-hour-a-week mainstream job, which eventually became full-time. Balancing study with any work can be exhausting, and I understand how sex work, with its relatively short hours and potential high pay, can be appealing to many students, who simply must work, yet struggle to manage both a mainstream job and intensive study. As my own mainstream work increased, my sex work decreased, although with job insecurity and a fixed-term contract I remained reluctant to lose my client base entirely. I gained my BSc and stopped escorting when I was offered a PhD. I had hoped to continue in academia after that – but, with no secure employment since completing the doctorate in June, I have returned to escorting.

It is hard to know whether my open association with sex work and the sex work community damages my future in academia, although it probably does. The stigma is structured so that it is more acceptable to say “I was a sex worker” but have “moved on” and am “doing better”. The general attitude in universities is that we just don’t talk about such things – like a parody of dinner with parents, the unapproving undertones hidden in the silence.

There was much criticism in September when the Sex Workers’ Outreach Project distributed material at the University of Brighton’s freshers’ fair. Apparently, recognising that student sex work occurs and taking steps to ensure that those involved have enough basic information to stay safe and healthy is a radical and disreputable act, and the university launched an investigation. Academia often talks about being “diverse” and “open”, but these are empty words. When confronted with raw, genuine diversity, universities tend to shun it, and close ranks around accepted norms.

Offering sexual services alone and indoors is legal in the UK, but soliciting in public is not. Brothels are also illegal, and the law states that “if more than one person is available in a premises for paid sex, then that is a brothel”. So two independent, voluntary sex workers who share a flat for increased safety and reduced isolation can be arrested for brothel-keeping. All moral judgement aside, it simply makes sense to ensure that students are aware of this – and of where non-judgemental help and support can be found. Yet a survey led by Swansea University, published in 2015, reported that university staff were themselves unclear about the law, and ignorant of where to refer students to.

I am often asked if I enjoy or hate escorting (because we adore dichotomies). I enjoy it more than I used to, but that is because many privileges have conspired to provide me with good clients and good working conditions. I like the opera or a fine dinner as much as the next person. That said, I would still rather be sat reading and writing with a cat on my lap most of the time. But who among us always enjoys their jobs, and wouldn’t rather not need to work?

The key point is that enjoyment or otherwise is irrelevant to whether sex workers should enjoy rights, safety and acknowledgement that their labour is a form of work. And if they were serious about inclusivity and community, universities would be in the vanguard of demanding it – for their students and for everyone else.

Adi MacArtney has a PhD in atmosphere-crust coupling and carbon sequestration on early Mars from the University of Glasgow. She was briefly a lecturer at the University of St Andrews, and taught the mechatronics-robotics summer schools at the University of Glasgow.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: More than empty words

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?