In his classic novel The Plague, the Nobel laureate Albert Camus draws a parallel between biological and ideological plagues. Just as the latter – in this case, the Nazi occupation of France – spurred small groups to resist the invader, so the bubonic plague in the novel galvanises individuals who are determined to combat it to join forces.

In both cases, they do so without direction or directives from above, instead devising approaches most suited to the changing conditions on the ground. This is a strategy that universities, especially in the US, should consider as they confront the challenge posed by Covid-19.

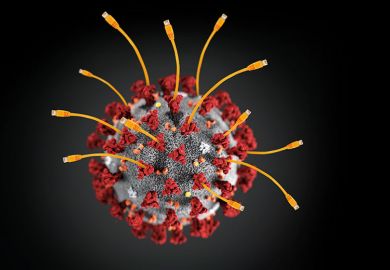

Our campuses, in effect, have been occupied by the novel coronavirus. While the initial responses varied over time and place, a pattern soon appeared: students were sent home as dormitories were closed, and professors went online as classrooms were shuttered. Shortly afterwards came the news of budget shortfalls, hiring freezes and demands from students, unhappy with the reality of virtual teaching, for refunds.

For now, students remain at home, professors remain online and administrators remain in limbo, attempting to divine whether the viral occupation will lift by this fall. What unites the three groups is the recognition that this in an untenable situation. What they have yet to recognise, however, is that a rigidly vertical management model is radically unsuited for our current challenge. Instead, universities need to adopt a flexible and horizontal strategy, one that goes beyond the idea of shared governance that most often means the faculty proposes and chancellor disposes.

Traditionally, professors are among the most autonomous of employees. With the unbridled growth of college administration, however, this freedom – which is sometimes abused – has been increasingly throttled, even for the tenured. In order to combat the current occupation, however, the return to such autonomy holds great promise. Faculty are ideally placed to reoccupy, by measured steps, the physical campus.

But how can this be done, given the physical limits of the classroom? In part, through the adoption of hybrid courses. It is both logistically difficult and financially disastrous to place dramatic limits on the number of students in large lecture halls. Video conferencing obviates the need for this, providing the same material to every student in an alternative, safe way. However, in order to avoid lurching from Zoom to bust, such platforms must be confined to lectures.

It is not that remote teaching cannot be done, but that it is difficult to do it well. Among the many lessons of the national lockdown is that teaching itself best takes place in a real place. The appeal of a teacher’s child giggling off camera or a student’s cat wandering across their background has worn thin, while the lethargy induced by staring at small boxes and jumpy images has grown heavier.

We are reminded of what Socrates already knew 2,500 years ago: real learning only takes place in a real place, a shared space. Hence, larger classes must be divided into a number of units, each small enough to follow social distancing rules, with no more than 10 to 12 students. This approach imposes a serious constraint that has, in turn, serious consequences. Given the logistical challenges of finding the necessary spaces on campus, we first need to rethink the nature of the campus. University administrations should allow individual professors to determine, within certain guidelines, where they could meet with students. It could be any open space, from parks and picnic grounds to playing fields and backyards, that are convenient for all parties.

The strategy of several smaller classes also cultivates the suppleness ideally found in team-taught courses. By collecting and comparing their experiences, team members learn from one another’s stumbles and successes. The former would be flagged while the latter would furnish the means to scale up quickly. Moreover, if lecturers were rotated, students would be exposed to the variety of philosophical inclinations among them. In addition, as with the French resistance networks, a kind of resilience to disruption would exist. For example, if one instructor were sick, students could migrate to different groups.

But there is a second consequence: more faculty would be needed to teach these small classes. A traditional resource is graduate students, but their limited numbers vary greatly across disciplines. Adjunct faculty, however, could also fill these newly created positions. They have long been the first responders for department chairs who find themselves with too many students and too few instructors. The savvy and flexibility of adjuncts – the ironic consequence of life in the academic underclass – would prove invaluable in these circumstances.

The final consequence of our idea appears the most daunting: how to pay for these battalions of teachers. Even Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal resisted providing federal aid for public education – but this exercise of frugality is now judged harshly by historians given the number of lives that were squandered as a result.

While it is difficult to measure the amount that state and federal governments would need to pay to cover both salaries and health coverage for this corps of emergency university teachers, we can be sure that it would be a fraction of the bailout envisioned for the cruise or airline industries. And the final destinations of those who benefit would be more enriching than any foreign harbour or airport.

Robert Zaretsky is a historian and professor in the Honors College, University of Houston. George Alliger is a consulting industrial psychologist living in Houston, Texas.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?