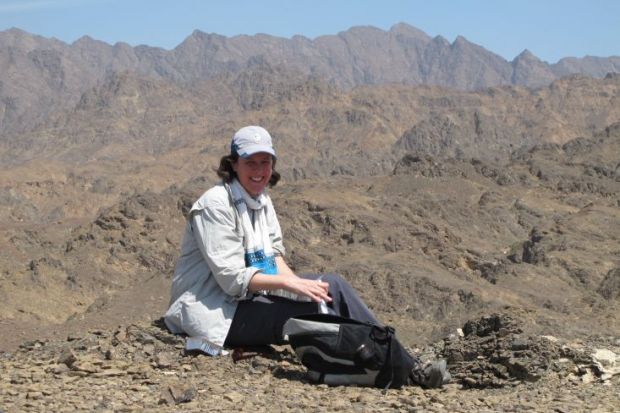

Tamsin Mather, professor of earth sciences at the University of Oxford, researches the science behind volcanoes and volcanic behaviour. In 2018, she won the Rosalind Franklin Award, given annually by the Royal Society to a woman for outstanding work in any field of science, technology, engineering or mathematics. She is also a winner of the Philip Leverhulme Prize and the L'Oréal-Unesco For Women in Science Award.

Where and when were you born?

Bristol, 15 December 1976 – a Wednesday.

How has this shaped you?

According to the nursery rhyme, I should apparently be “full of woe”, and I am – but only sometimes. I also moan every year that Christmas overshadows my birthday and am reminded every year that I am lucky I was born 10 days early! Bristol has a strong independent identity and plenty of hills and wonderful nearby countryside. It was a great place to grow up, although I don’t miss the drizzle.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

Not as diligent as I wish I had been or as I tell my students to be. I worked extremely hard at school, and when I got to university, I wanted to experience many things alongside the academic work. I spent a lot of time socialising, trying new sports and clubs. I did knuckle down in my third and fourth years and loved my final-year research project.

How did you get into your research area?

Largely by accident. After my chemistry undergraduate degree at the University of Cambridge and some time out of science, I wanted to do a PhD in earth or environmental sciences. For the application to the department in Cambridge, I had chosen a project on ancient ocean chemistry, but there was a space on the form for a second-choice project. The project on the tropospheric chemistry of volcanic plumes was one of the few others I understood the title of, and I’d enjoyed visiting an erupting volcano on Réunion in 1998. I put it down and, when the offer came through, I decided I wanted to swap to the volcano project.

Have you had a eureka moment in your career?

Not [a big one] really, but lots of little ones. Every time I work out how something works – however small it is – it feels in that tiny moment like I’ve solved something major.

How did it feel to win the Royal Society Rosalind Franklin Award?

Amazing. Carol Robinson, Dr Lee’s professor of chemistry at Oxford, nominated me. She is someone I like and admire greatly, so being put forward by her was a massive boost. To win it was incredible and very unexpected. The evening of the lecture was great, after I had gotten over the nerves, and is a wonderful memory – especially the part where my son, who was sitting in the front, gave me the “loser” sign at the end while I was taking applause. It has also given me the opportunity to undertake an outreach project to promote women and girls in STEM, which I am really enjoying.

What has been your most exciting part of your research?

Making measurements at active volcanoes is very exciting. The longest field trip I have done so far was six weeks in Chile during my PhD. Highlights included climbing Lascar volcano (5,500m altitude) in the Atacama Desert – it felt like the top of the world – and sliding down the ice cap of Villarrica volcano after days sampling in the fumes at the crater rim.

What are the best and worst things about your job?

The best things for me are fieldwork and working with local scientists, getting new data in and making sense of it, and seeing students succeed. The worst things are exam marking, when a grant or paper that you put your all into gets rejected and when unnecessary bureaucracy takes too much of my time away from the really productive stuff.

What are the challenges faced by women in STEM?

Close female colleagues have experienced some terrible and blatant sexual harassment, and universities globally need to combat this sort of behaviour. These cases are at one end of a spectrum of cultures and structures that add up to disadvantage under-represented groups in STEM.

Are they being addressed?

Initiatives such as Athena SWAN have made academia think about these issues. There is certainly positive progress, but it is slow in some areas. The Athena SWAN process is very bureaucratic and can end up taking time away from the very people it is supposed to be supporting. I really appreciate that volcanology in the UK benefits from having great female scientists at all levels of the career ladder. I am also very mindful of the BAME under-representation in geosciences in the UK.

What one thing would improve your working week?

At least a day a week free of distractions, to think, read and write.

What divides your life into a ‘before’ and ‘after’?

When our son was diagnosed with leukaemia in October 2014. The treatment lasted three and a half years, and we met many other families on the ward. Now we just go in for three- to six-monthly check-ups, but I don’t think my perspective on the world will ever be the same.

What would you like to be remembered for?

I had a bit of a crisis about this when our son got ill. I felt that everything that I did was completely pointless compared with the amazing people who had discovered the drugs that gave hope to us and other parents on the ward. I don’t dwell on this so much now, but just try to do science that I am proud of and interested by on a daily basis, and to make the most of it when it might be useful to the world more widely or when it inspires others.

anna.mckie@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Samuel Stanley will be the next president of Michigan State University. Professor Stanley, who has been the president of New York’s Stony Brook University since 2009, will take the helm at MSU in August. He will be the institution’s first permanent president since the resignation last year of Lou Anna Simon, who was criticised for her handling of a sexual abuse scandal. Professor Stanley said that he recognised that the university community had “been profoundly troubled by the events of the past years that have shaken confidence in the institution”. “We will meet these challenges together, and we will build on the important work that has already been done to create a campus culture of diversity, inclusion, equity, accountability and safety,” he said.

Cisca Wijmenga has been appointed rector magnificus of the University of Groningen, overseeing the institution’s academic activities. The professor of genetics will be the first woman to take up the role and only the second female board member in the university’s 405-year history. Professor Wijmenga, who in 2015 won the most prestigious research prize in the Netherlands – the Spinoza Prize – will succeed Elmer Sterken in September. Her appointment “means that an acclaimed academic will be at the helm of our teaching and research”, said Tjibbe Joustra, chair of the university’s supervisory board.

Mark Holton is joining Middlesex University in August as chief people officer. He is currently director of group organisation development at Coventry University.

Mercedes Ramírez Fernández will become the University of Rochester’s first vice-president for equity and inclusion. She is currently associate vice-provost for strategic affairs and diversity at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

Karin Gwinn Wilkins has been announced as the new dean of the University of Miami’s School of Communication. She will move from the University of Texas at Austin and succeed Gregory Shepherd in September.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?