A neuroscientist who identified the crucial roles of glial cells has died.

Ben Barres was born Barbara Barres in West Orange, New Jersey in September 1954. He obtained a scholarship to study life science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1976) and went on to a medical degree at Dartmouth College (1979).

Although he followed this with an internship and residency in clinical neurology at Cornell University, Professor Barres grew increasingly frustrated with the medical profession’s seeming inability to cure or even understand neuronal degeneration. Having observed that glial cells were a constant presence near the lesions in degenerating brain tissue, he resolved to illuminate their significance. To do this, he changed tack, joining Harvard Medical School’s neuroscience programme in 1983 and completing a PhD in neurobiology in 1990. This led to a postdoctoral fellowship in the lab of Martin Raff, then professor of biology at UCL.

An utterly committed researcher, Professor Barres would regularly work until 2am or 3am. He “slept on the floor of my small office”, recalled Professor Raff. “Every morning when I arrived and opened the door, it would whack him in the head – he eventually learned to sleep facing the opposite direction.”

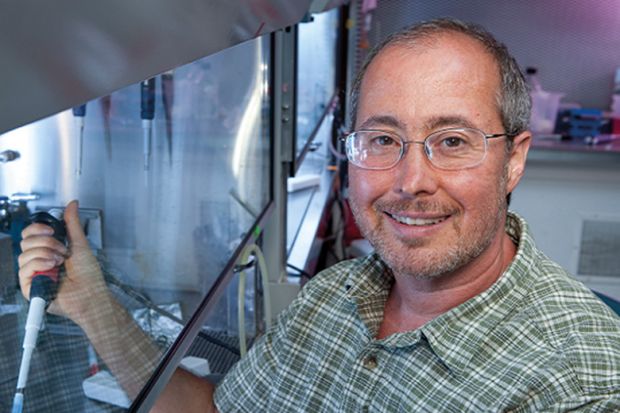

In 1993, Professor Barres moved from UCL to Stanford University. Having started as an assistant professor, he was promoted to a full professorship in 2001 and then chair of neurobiology in 2008.

Although glia make up nine out of every 10 cells in the human brain that are not neurons, they were long regarded as relatively unimportant. Professor Barres’ achievement was to find ways of growing them in isolation and demonstrating that they were critical to maintaining the brain’s overall architecture of synapses. Their vital role means that their failures may well be responsible for many neurodegenerative disorders.

Research in Professor Barres’ lab has, for example, strongly implicated inflamed or “reactive” astrocytes and microglia in conditions such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, as well as in multiple sclerosis and glaucoma. “If you took the Barres lab out of the field of glial studies,” noted Professor Raff, “there would be no field.”

Despite suffering from prosopagnosia, the inability to recognise faces, Professor Barres was a generous mentor who shared his data as widely as possible. He was also a great champion of women (and minority groups) in the academy, often using talks to highlight the different responses to his work he had received as a male and female scientist – having transitioned in 1997 at the age of 43.

Professor Barres died of pancreatic cancer on 27 December 2017.