Rapid globalisation in higher education is down to “massive governance failures” that mean developing world governments respond inadequately to the vast hunger for knowledge among their populations. But Pratap Bhanu Mehta, president of the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, warned that such countries should avoid copying a single Western model in their race to build university systems.

Speaking as part of a debate on “the university in a global context”, held at Tate Modern in London on 3 June, Dr Mehta said the “resilience” of the UK and US systems was based “on the diversity of their institutions”.

As a result, he said, developing countries should avoid adopting any single model they found there.

Dr Mehta also said that although productivity and job creation do not necessarily go together, universities were often burdened with the unrealistic hope that “if we get higher education right, it will solve the problem of jobless growth”.

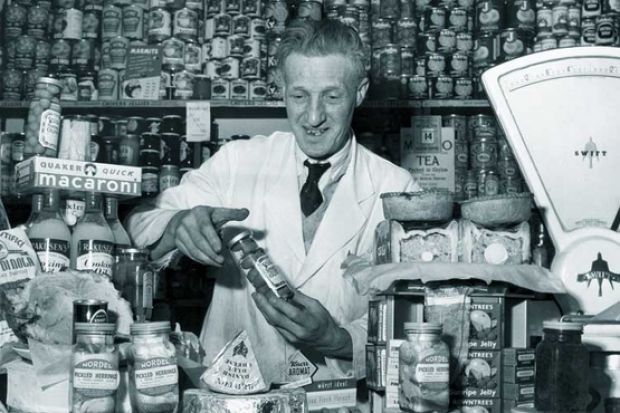

Meanwhile, Richard Sennett, centennial professor of sociology at the London School of Economics, recalled that when “the Chinese began to put serious money into research in the late 1980s”, they had adopted what he called “the shopkeeper model”. Everything was tightly controlled and designed to answer carefully defined questions – and the results were “dismal, boring and produced no patents”.

That had led them to turn instead to “the MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] model”, based on trial and error and the acceptance of inevitable failures, just as painters often scrape away what they have done and start again.

“This might not sound like a sensible model,” Professor Sennett continued, “except that it works and produces tons of patents.”

His fear was that many leading Western universities were now “returning to the shopkeeper model” by embracing “accountability” and “walking away from the idea of discretionary spending and personal judgement”.

Waste not, want not

Stefan Collini, professor of intellectual history and English literature at the University of Cambridge, also spoke up for the “wasteful” aspects of the MIT model and argued that “the best way to get academics to perform their public task is by leaving them alone a good deal”.

With “intellectual agendas largely set by a few well-funded First World universities”, he said, it was important to create counterbalancing institutions elsewhere that were not driven by short-term goals.

But responding to what he called “the Sennett-Collini critique”, universities and science minister David Willetts claimed that “the Ivy League is a red herring” because “Stanford and MIT are not relying on public money for their big speculative work. Much though I admire that model, the issue is how we can allocate public money to create departments [like theirs].”

Today, the minister suggested, “much of the world is facing its Robbins moment”, trying to address the issues of university expansion that the UK first encountered after the Robbins report of 1963.

When the government of Indonesia came asking for help with its plans to expand student numbers by a quarter of a million a year, Mr Willetts had been disappointed by the response of UK universities. He was also “unclear how much the MIT/Oxbridge model can really rise to the challenge”, he said.

The debate was chaired by Paul Webley, director of Soas, University of London, and formed part of a series of lectures on global citizenship, coordinated by the communications organisation Zamyn, ahead of next week’s G8 summit in Northern Ireland.