How to make sense of UK entry requirements

Typical offers, contextual offers, predicted grades – it can be hard for counsellors to work out what the entry requirements really are for UK universities. This guide explains the process

You may also like

Once students applying to UK universities decide which course they would like to apply for, they usually look at the entry requirements. This can be a minefield, making it challenging – and necessary – to provide them with good advice.

University web pages often display more than one set of entry grades. This may be in the form of a band of offers – for example, AAA-ABB. Or they may display a “typical offer” and a “contextual offer”. This can cause confusion for students who are trying to work out if they are competitive for a specific course at a specific university.

Grades on entry – and the importance of context

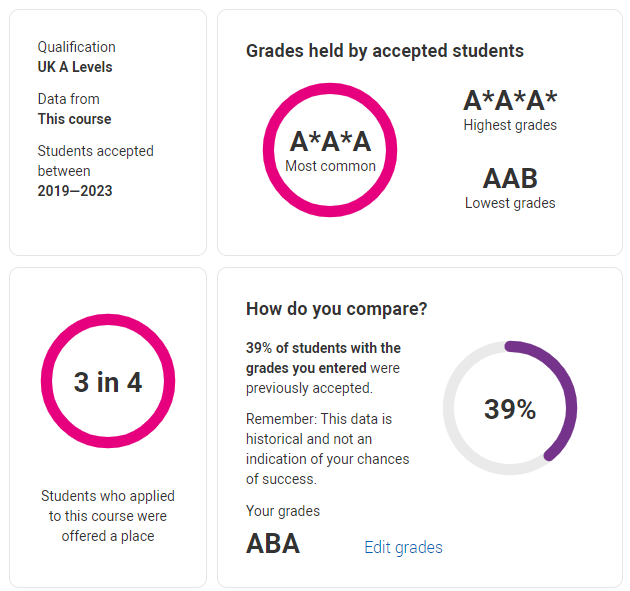

To aid students with this, Ucas released a Grades on Entry tool, which shows students what grades those who have been previously admitted on to a particular course achieved. So, for example, the Grades on Entry tool for history at a well-known, academically elite university looks like this:

What is not shown is the context of the 39 per cent of students who were awarded a place with these grades – they could have had extenuating circumstances, or could have met the criteria for the widening participation programme.

This can create challenges when advising students armed with data but without the experience or skills necessary to critically analyse its meaning in context.

Making sense of offer grades

Within this, there are further trends of note:

Offer versus entry requirements

Universities are, of course, free to decide on the offer they make to a candidate beyond the advertised entry requirements. For example, one student we worked with applied for a computer science course with typical entry grades of A*AA, and was offered a place with AAB. His predicted grades were A*A*A*A and he had no relevant contextual information or extenuating circumstances.

Offer versus predicted grades

While predicted grades may inform a university’s decision to make an offer, the university does not have to adhere to predicted grades. We worked with a student who applied for a law course with predicted grades of ABC, and was made an offer of BBB.

Missed offers

Universities can accept students who miss their grades for the offer they have confirmed. For example, one student we worked with had an offer for law of AAB, and was accepted on to the course having achieved grades of CCC – missing its offer by five grades.

Indeed, an increasing number of students we work with who missed their offers were still accepted by their firm choice university.

None of these trends is related to university contextual offer-making, which is well documented on many university websites, for example at the University of York.

Playing the game strategically

All of these trends make advising students in this ever-changing landscape a particular challenge for counsellors. It leads to reasonable questions about how best to play the game, while we try to marry the aspirations of our students to the realities of these trends.

For example:

- If a student may be let in to a university if they miss its offer, how important is predicted grade accuracy for counsellors?

- And how does this affect the push-pull between what students want their predicted grades to be and what staff professionally judge is most likely?

- How do we best advise students when the published data is at odds with what we are seeing annually with our own students?

- How do we manage expectations of students who have access to the Grades on Entry tool?

These questions are compounded by headlines claiming that international students may be offered lower entry grades. Both domestic and international student, as well as their parents or guardians, may need further support in separating reality from sensationalism.

One of the ways we can best help students manage these trends is to understand and make use of the entire Ucas process, not just the elements preceding the equal-consideration deadline. Ucas Extra, early Clearing and Clearing after results day all offer different access points to the Ucas process, which might allow an aspirational student who has been unlucky securing a place to find something suitable.

It is invaluable for counsellors to ensure that the narrative around these processes highlights that they are for everyone to use, rather than a route for those who have missed offers. We have had students use these processes because they changed their mind about the university or course they had accepted, applied late, achieved higher or lower grades than expected and more.

Given the financial pressures on universities, such trends in flexibility of offers are perhaps here to stay for a while. Of course, after 2030, the demographic dip of UK 18-year-olds may compound these issues. But understanding the trends gives us better capacity as counsellors to help students play the game – strategically.