How to protect students’ self-esteem during the university application process

Negative self-talk, a tendency to avoid challenge and difficulty accepting compliments can affect not only a student’s mental health but the university application process as well

Sponsored by

You may also like

Very few things can invigorate – or shatter – a student’s self-esteem like the university application process.

We observe this up close as college counsellors. Even if we did not study psychology, we know intuitively the signs of low self-esteem in a student. Characteristics such as negative self-talk, being overly critical or perfectionist, avoiding challenges, social withdrawal, and difficulty accepting compliments can affect not only a student’s mental health but the university application process as well.

Conversely, if a student has high self-esteem, that’s clear, too. Students who are not afraid of feedback, are able to set boundaries, are not people-pleasing, do not feel inferior and are not afraid of setbacks can navigate school life and the challenging university application process with more ease.

What is self-esteem?

But what is self-esteem exactly? It is a slippery concept for researchers studying psychology, having been approached in numerous ways.

It also has a controversial past. If you lived in the US in the 1970s and 1980s, you may remember an almost obsessive focus on self-esteem – this was the self-esteem movement. Having once heavily influenced the education sector, there has since been a re-evaluation and a realisation that zeroing in only on self-esteem can do more harm than good.

Despite its controversial history and ambiguous definition, self-esteem is still an interesting concept for us to understand as college counsellors. By understanding the nature of self-esteem, we can help cultivate it in our students to a healthy degree, as we support them in the university application process.

Self-esteem has many definitions in psychological research. This article will review one framework deemed especially relevant to college counsellors, but just keep in mind that there are other ways to approach this concept.

To understand this framework, first imagine undertaking a task that you’re particularly good at, which matters to you greatly. Perhaps it’s talking to students, baking, skiing or playing the piano. Engaging in this activity boosts your self-esteem, doesn’t it? This is one component of self-esteem: competence.

However, if you picture a person with good self-esteem, perhaps they’re not doing something in particular – rather, they’re just feeling good about themselves. Respecting and regarding oneself as a person of worth, harbouring a sense of satisfaction and a positive attitude is the other component of self-esteem – worthiness.

Both of these are important but distinct components of self-esteem. What happens when we combine them?

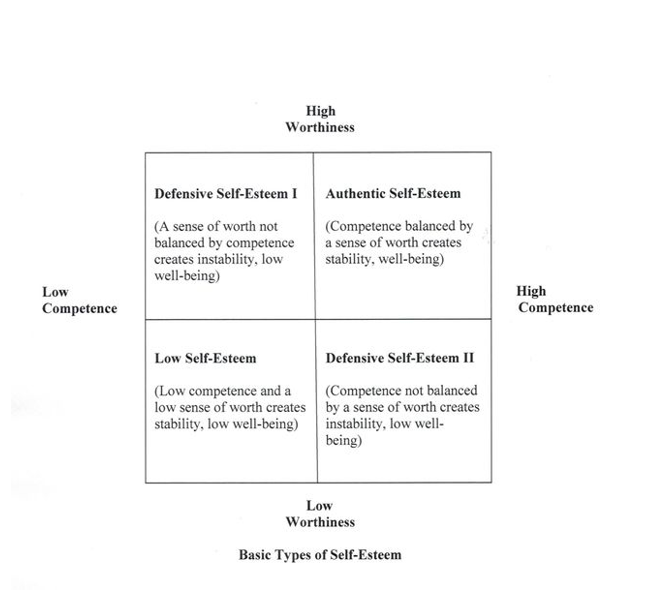

It can result in a matrix like this:

High competence and high worthiness

Let’s picture a student who scores highly on both competence and worthiness, which is the best-case scenario. The student is likely to be: actively concerned with living out positive, intrinsic values; not defensive but optimistic; and harbouring varying degrees of openness to experience. Students who score high on both aspects are easy to spot and can be a joy to work with.

However, if a student scores highly on only one component but low on the other, that results in different kinds of self-esteem.

High competence but low worthiness

An individual with high competence but low worthiness is characterised as success-seeking, anxious about and sensitive to failure, or with an exaggerated need for success and power. You may see these features in a student who has very high grades and demonstrates other societally approved markers of success and is focused on continuing to build up their achievements but is unable to foster a deeper sense of self-acceptance.

Low competence but high worthiness

Conversely, an individual with low competence but high worthiness may be approval-seeking, have an exaggerated sense of worth regardless of competence level, and be reactive to criticism. Picture a student who falls short of the admitted student’s academic profile for a competitive university but still believes they are a fitting candidate, based on an internal measure of worth.

Low competence and low worthiness

Scoring low on both components is described as being characterised by a concern to avoid further loss of competence or worthiness. Students with low competence and low worthiness are focused on protecting their current level of self-esteem, to prevent it dropping further. Unfortunately, this can result in withdrawing not only from the university application process but from social and academic spheres altogether.

How do the four types of self-esteem relate to college counselling?

So why is this relevant to college counselling?

First, it can help us understand what motivates students’ behaviour in a more nuanced and compassionate way.

Secondly, the university application process requires both competence and worthiness. As educators supporting their university applications, we can contribute to fostering both components, thus boosting a student’s self-esteem. Effective college counsellors are probably doing this already, and this framework provides further rationale for their practice.

How to build competence

Encourage any activities that involve skill development or require students to try their best to achieve (in the form of extracurriculars). These use competence to overcome challenges.

Another way to build competence is by influencing one’s environment in a meaningful and satisfying way – which is what universities with holistic admissions process purport to measure in a student’s application.

If a student is unable to make great strides because of a low starting level of self-esteem, you can find ways to boost competence – breaking down a project into small steps, such as opening an application platform, researching two ways to get involved or attending a club’s weekly meeting.

How to build self-worth

Worth can be built in two ways. Firstly, students build self-worth when they become a part of healthy relationships, groups and communities, or when they do volunteer work.

Peer relationships are an important driver of self-worth for adolescents, but genuine connections with caring adult figures can also matter. Fortunately, given our job responsibilities, we get to know a great deal about the student, in comparison with other staff at the school – and such knowledge can more easily build rapport and trust. So, don’t shy away from forging deep connections with our students.

Students can also increase their sense of self-worth by acting more virtuously. Admitting mistakes, making up for errors, doing their duty, not lying on their university applications, standing up for rights of others – encourage such virtuous behaviours in students’ engagements with the school community, and in their university applications.

University applications and self-esteem

Also, certain stages in the university application process will diminish a student’s sense of competence or worth.

A rejection from a university can certainly shatter both. This is why reminding students of their competence and worth – which remain constant no matter what an external person or institution might say – is important.

The predicted grade process can also undermine a student’s competence. Our job as college counsellors is to ensure that the grades are a realistic representation of a student’s academic potential yet at a level that does not demotivate them completely – while maintaining this balance with the student’s competence.

Finally, as can be seen in the matrix above, striking a balance between promoting competence and worthiness is important. Sometimes, a student may only be seeking one component and not both.

To figure out why, examine what is being highlighted in the student’s environment. Sometimes society may be hyper-focused on showing off competence. Or it may determine that worthiness is solely based on extrinsic factors such as fame, appearance, money – or university offers.

We cannot necessarily blame students because this is a developmental stage where they are absorbing the values of their surroundings. But reminding them of the importance of fostering a healthy sense of self-esteem based on internal values and virtues is important. This is our task as educators.