Much of the debate in global higher education in recent years has revolved around whether the income that universities receive – either from fees or elsewhere – is used to improve teaching.

Critics have often pointed to the growth of expensive facilities, especially in countries such as the US and UK, as evidence that money is being ploughed into capital expenditure rather than staff.

But is there any evidence for this in the data around expenditure on higher education and teaching quality?

One possible way to examine this is to look at class sizes in universities, which, rightly or wrongly, are often held up as one of the clearest “input” indicators of quality when it comes to teaching (see here for a list of the institutions with the best staff-student ratio according to Times Higher Education World University Rankings data).

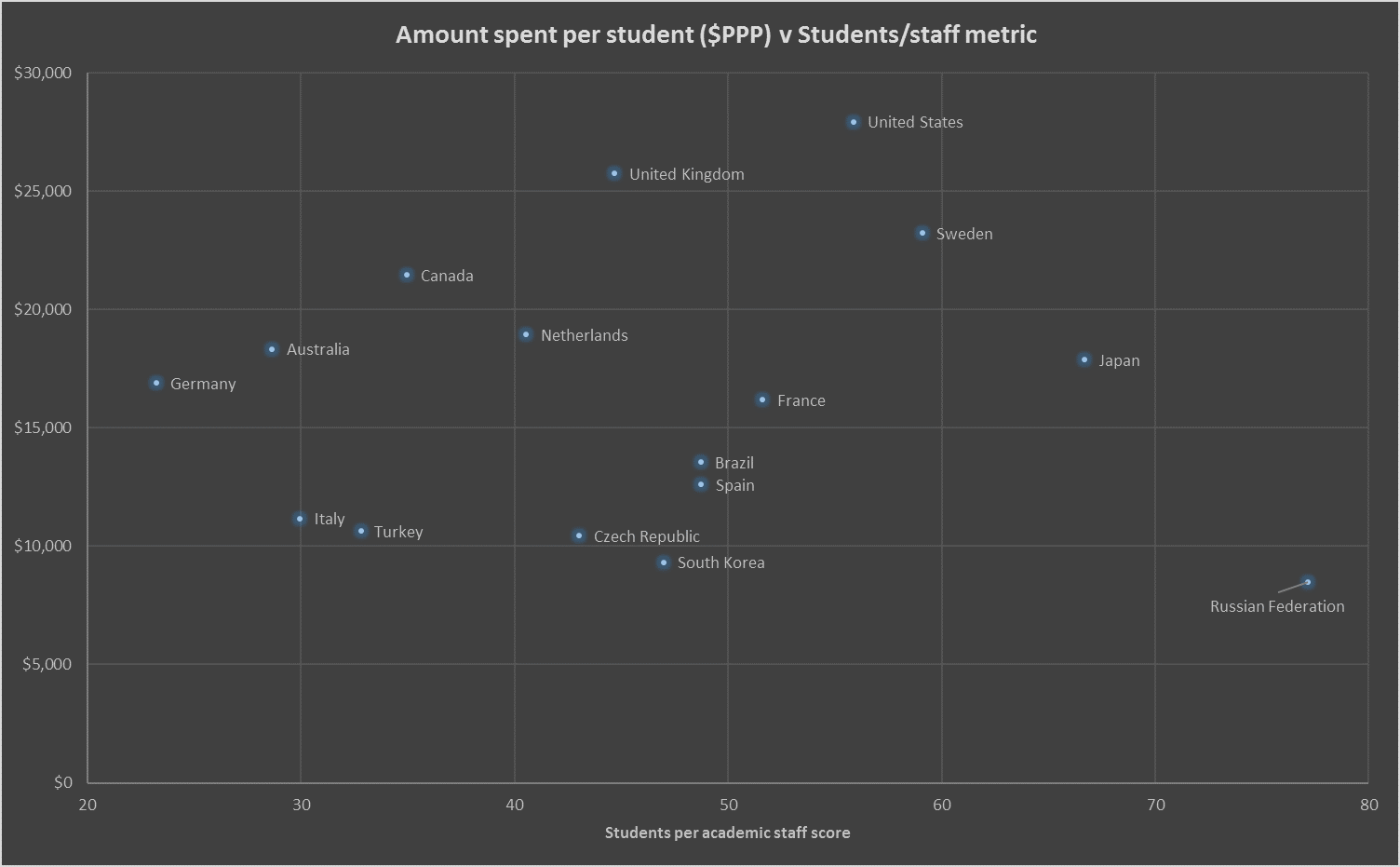

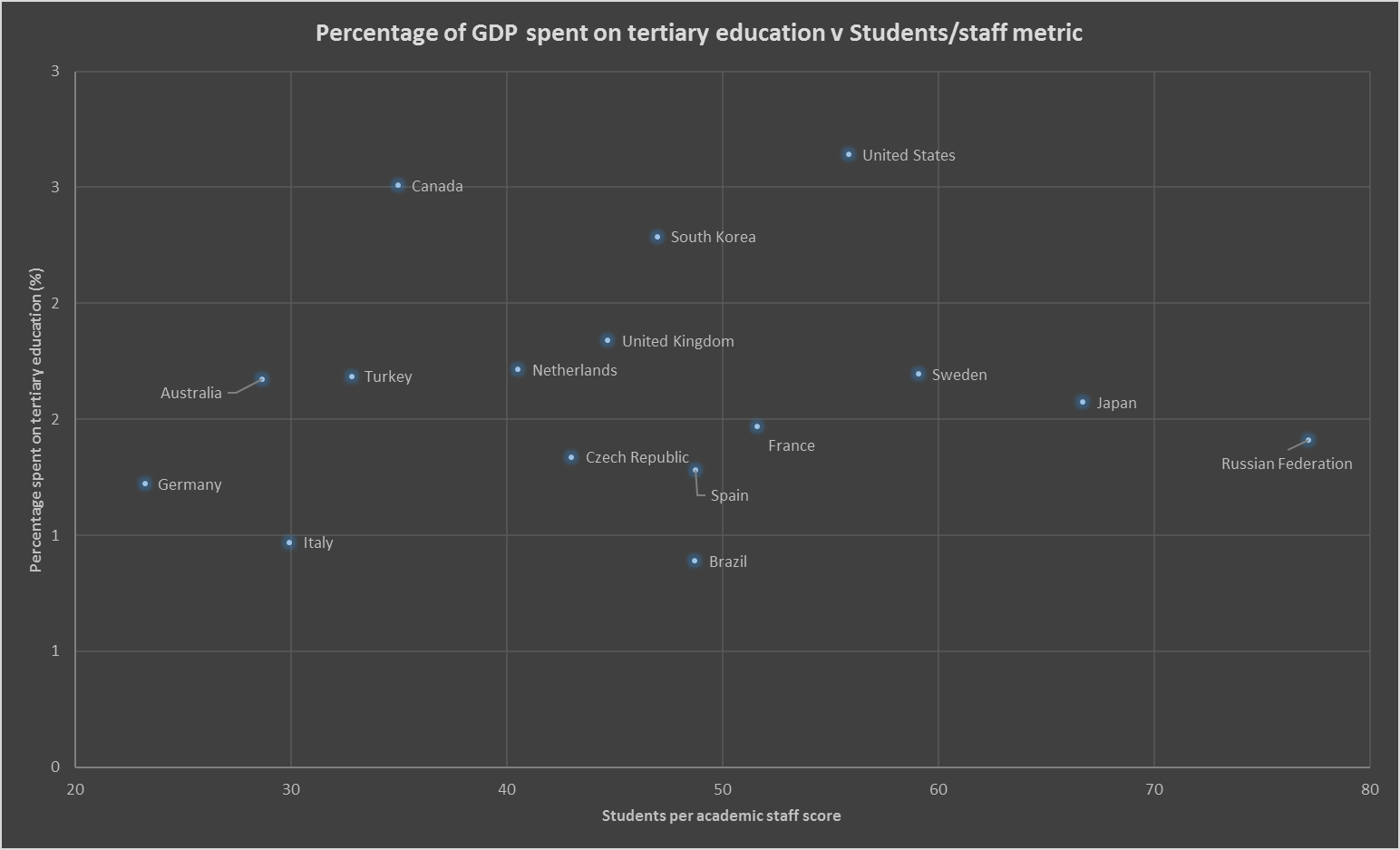

If a country's average score for the students per academic staff metric in the rankings is compared with two measures of higher education spending from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, some interesting results emerge.

For some countries, it does appear that the more is spent on tertiary education – both as a percentage of GDP and per student – then the greater a country’s average score on the staff-student ratio metric (note: this score is a mark out of 100, and not the actual number of students per staff. A higher score indicates a better staff-student ratio).

For instance, the US spends a relatively large amount on tertiary education (partly because of the high tuition fees at many private institutions) and seemingly, in return, sees high average scores on the metric.

However, there are many examples of countries that do not follow this trend.

Russia, for instance, has one of the smallest spends – in GDP and per student terms – of countries included in the OECD figures (Russia itself is not a member of the OECD but it is included as a “partner” country in the statistics), while coming up very high for the staff-student ratio score. Other countries have a high staff-student ratio despite spending modest amounts: Sweden and Japan are notable examples.

There are also countries such as Germany and Australia that as nations spend relatively high amounts on tertiary education, according to the OECD data, but which have relatively low average staff-student ratios.

According to THE data scientist Billy Wong, one of the key factors when looking at staff-student ratios across different countries is the cost of staff. Where the cost of staff is high there could be a concerted effort to find ways around employing more people or to keep costs down in other ways such as delivering more higher education online.

"A number of factors have to be borne in mind when looking at the students per academic staff metric and one of the most important is the cost of staff in different countries," Mr Wong said.

"In wealthier countries the cost of staff is often very high and in relatively poorer countries the cost may be much lower. This is one reason why countries like Russia score well on staff-student ratio but richer nations like Germany do not."

There may be other points to bear in mind with the analysis: a declining youth population may affect staff-student ratio, as in Japan. Staff-student ratio may not always be a good indicator of class size – a university may have a lot of staff, therefore affecting the ratio, but they could be engaged in a lot more research than teaching. And although only countries with at least 10 universities in THE’s rankings dataset (and available OECD data) were included, some institutions with a very high score on the metric could skew the average.

Despite this, perhaps the most interesting examples in the analysis appear to be wealthy countries where staff costs would be high but which still score at the top end for staff-student ratio. Apart from Japan, this pinpoints the US, Sweden and France as having potentially invested more higher education funding into keeping class sizes small.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login