For half a century I played cricket with academic scientists. In most cases they enjoyed their research and found it satisfying, but in many cases they dreaded what they called “writing up”. I, on the other hand, loved language and loved writing, but found academic writing increasingly fraught because it became more and more distant from good writing.

All my adult life I have written both for academic journals and for more popular outlets, such as newspapers and magazines. Academic writing meant to me a sense of solidity of achievement and professional status, while the more popular media meant a broader audience but also money. While academic journals generally did not pay, newspapers and magazines did (and, despite the internet’s destruction of advertising and subscription revenues, some still do).

I received my first cheque from The Countryman in 1972. It was for £20, which translates to £200 now. In the current decade, the most I have ever been paid for an article is £700, whereas in the 1980s I received up to $1,000: in current values, more than three times as much. So I doubt that a young academic would have quite the same financial incentive as I did to write in a popular style. But assuming they could fit it in alongside churning out the academic “outputs” demanded now by research assessment, they still might find it enjoyable.

I was always unwilling to call myself a “writer”. Nearly everybody writes something, I didn’t make a living out of it and if you said you were a writer many people would assume fiction – or that they should have heard of you. Instead, I have said I am an “essayist”. It was the relatively short writings of the likes of David Hume and George Orwell that made me think, “I want to do that”. And most of the great essayists had day jobs.

But nor was I one of those academics whose paid writing was completely separate from their academic work, like Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll) or G. D. H. Cole. I wrote about the same things in both contexts – politics, sport, the environment and education being the principal topics. That said, the way I went about it was very different.

Although some basic techniques, such as choosing vocabulary and constructing paragraphs, are superficially similar, I would argue that in many respects academic and popular writing are opposites.

In writing a marketable essay, your first objective is to find a subject, an approach and probably an opening that a specific editor believes will secure the attention of his or her readership as they envisage them. The editor may be wrong about that readership, of course, or intent on changing it – so a change of editor could result in a very different reception. A magazine I wrote regularly for changed editors and the new man told me, “I’m not remotely interested in sport or what goes on in the North of England”. Since that was what most of my previous pieces had been about, that message came as rather a shock.

I could, of course, simply pitch my sport and North of England articles elsewhere – but it isn’t quite that simple. I found that if you wrote an article with one outlet in mind, it would have to be substantially modified to fit another one. This was usually for several reasons, including preferred length, style and what sort of knowledge or level of interest could be assumed. Writing on higher education for Times Higher Education is different from writing for The Telegraph, which is different again from The Critic.

The target you have in mind for an academic article is your “peers”, a limited number of people who, themselves, write about the same or similar subjects and have to read what you write as part of their jobs. Whereas commercial writing is an attack – you are seeking to grab attention – academic writing has a huge defensive dimension. We do, after all, actually talk traditionally about “defending” a thesis, and part of one’s thinking must be along the lines of “Can I actually reference that?…Have I shown sufficient awareness of all the aspects and arguments involved?”

To illustrate this, I set myself the task of picking a passage from one of the dozen or so books in my study that I have recently received for review or comment. I allowed myself five minutes, but the task took 30 seconds as I opened an edited book and read:

“While social class, income, nationality and race are important factors influencing the experience of mountaineering and ability to travel to high-altitude mountains, gender has persisted as a key category of identity, difference and inequality within climbing and mountaineering cultures.”

The subject (different perceptions of Mt Everest) is interesting. But there are upwards of a dozen abstract nouns in a single three-line sentence that expresses an observation which, to put it politely, is far from surprising and might have been said very simply. It’s as if the author is saying, “I’m aware of all aspects so don’t mark me down on that score.”

The sentence is unwieldy despite the fact that it is completely innocent of any jargon, in the sense of terminology that only a specialist would understand. I remember my father looking at my first book and remarking that it was full of jargon. He was an educated man, but his education was entirely in the humanities, whereas mine was in philosophy and the social sciences. I had to acknowledge that he was right. And though I felt that use of the disciplinary jargon was necessary to stake a claim to be part of the discipline, I regretted the barrier to understanding that it raised for the general reader.

That barrier is extremely high in much of natural science and social studies and even higher sometimes in forms of cultural and literary theory. Traditional big-event historians seem the most immune to it. Of course jargon can become part of the common language, as successful academic inventions like “subculture” or “supply and demand” or “QUANGO” have done. But a great deal of academic discourse remains obscure and, worse, is part of a temporary fashion. When I studied politics, for example, in the early 1960s “corporatism” and “civil society” were obscure and anachronistic terms, but they were revived with intensely disputed meanings in, respectively, the 1980s and 1990s.

Some people find it much easier to drop the jargon than others, however. I was party to an almost experimental relation between academic and normal writing in so far as for many years I wrote for and knew the editor of the social studies weekly magazine New Society. What happened quite often was that researchers would be asked to turn their 10,000-word journal article into a 2,500-word piece for a much larger market. As well as brevity (obviously), this demanded writing that was more lucid and assertive, less nuanced. Usually, it also required a beginning that seized the reader’s attention. It was clear that some people took to this like a duck to water, with a sense of being released from the pen – but it made others very nervous and they found it extremely difficult.

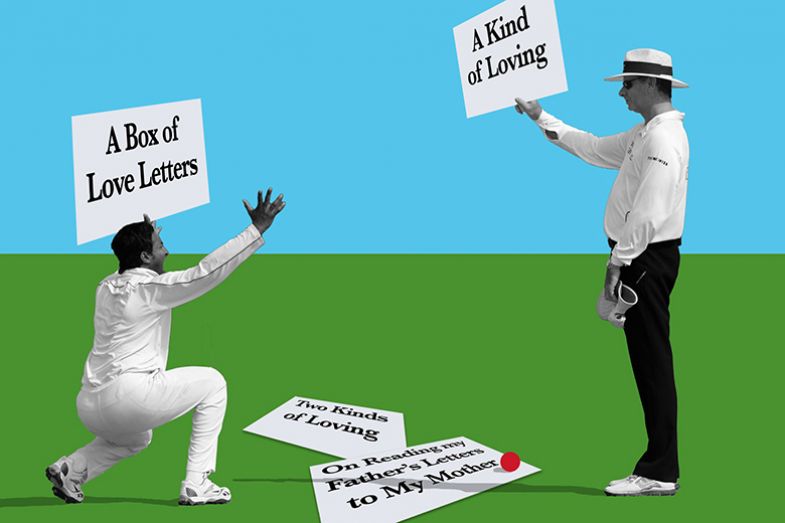

Even more than their jargon-counts, the two kinds of articles are distinguished by their titles. These are always important: after all, whatever you have written, far more people are going to read the title than the text. But in commercial writing, authors’ suggestions for titles are routinely overridden by editors or sub-editors. They will be entirely convinced that they have the knack of attracting the public’s attention and that you don’t – often by referencing the title of a song or novel.

Thus, in well over half a century of writing for money, I have rarely got my own title on to the printed page. I haven’t kept a record, but I can quote a recent example. During Covid, I finally got round to reading the letters my father had sent to my mother during the three and a half years he had been away from her during the war. It turned into an essay about how different the experience of life (and especially of marriage) was for someone born in 1946 as opposed to 1912.

Of course, as an “essayist”, I would have liked to call it, “On Reading my Father’s Letters to My Mother”, but nobody would allow me to get away with that. I actually called it “A Box of Love Letters”. It appeared as “A Kind of Loving”, which is the title of Stan Barstow’s 1960 best-selling novel and a 1962 film adaptation. “Two Kinds of Loving” would have been both more accurate and more original.

At least in academic writing you usually get to use your own title. But is that a good thing? There’s an interesting approach to that question in a 2014 blog by Patrick Dunleavy called “Why do academics choose useless titles for articles and chapters? Four steps to getting a better title.” (That, presumably, is a good title? I offer no opinion.) The argument is that academics tend to abuse this freedom in one of three ways: by being “cute” or obscure or silly-clever, by implying that their tiny topic is far bigger or more significant than it really is, or by stuffing in unnecessary references (typically Classical or Shakespearean).

It is as if the constrained world of the academic article allows one bizarre shot at self-expression. Do authors think they are attracting attention? Or defiantly showing that they don’t care? Again, you can pull out literally a million examples instantly; I offer, “A Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose Is a Rose, but Exactly What Is a Gastric Adenocarcinoma?” (Journal of Surgical Oncology, 1998, capitals as in original). For the record, my favourite academic title is H. A. Prichard’s “Does Moral Philosophy Rest on a Mistake?”, in Mind 1912, because it’s clear and so bold as to challenge an entire discipline (and also because at my first economics seminar, my friend and contemporary, the philosophical prodigy Gareth Evans, referenced it by informing the tutor that economics was based on a mistake).

Arguably the biggest difference of all between the two genres is their referencing conventions. I was introduced to university work via the Oxford tutorial system. You read an essay twice a week to a tutor. There were no references whatsoever. You just said things about the appointed topic with a view to keeping the tutor awake, providing some ideas that might be discussed or sounding interesting.

It is often said that the system prepares people for Prime Minister’s Question Time or panel shows rather than scholarship, but I submit that it is also a much better training for writing in the broader sense than is what goes on in most universities, where you have to hand in written material that demonstrates that you have read the prescribed texts and can quote and reference them.

I never referenced anything until the time came to publish. I did learn to like footnoting (or endnoting if you must) because you can bung all sorts of things in there, including jokes and anecdotes. But what I really loathe is the Harvard system of referencing, which has become the norm in most academic publishing.

From the point of view of a writer, it is clumsy and pointless. You are supposed to list sources and then refer to them in brackets in the text. What do you put on the list? I’ve been reading for well over 70 years and it’s all relevant. What do you mean when you put something on the list? That you are cognisant of it? That you’ve read it? Learned from it? Know what you’re saying only because of it?

Either way, Harvard referencing is vastly overused. What is the point of, “The Battle of Hastings was fought in 1066” (Smith, 2025) – you should reference only when statements are little known or disputed. And when you say, “The Battle of Hastings was the most important battle in English history” (Smith, 2025) are you saying that or are you just quoting Smith? The whole thing seems fraught with ambiguity and potential deceit, quite apart from breaking up prose in an ugly way.

This is a good example of the way that academic writing insists on conventions that burden both writer and reader alike. I concede the need for academics to sometimes write on subjects whose complexity demands a depth of subtlety and breadth of vocabulary that even an educated general public might struggle with; that is no doubt the situation that many of my cricketing scientist friends faced. But wilfully turning that public off by wallowing in unnecessary jargon and grating convention feels like a wholly unnecessary slog.

Lincoln Allison is an emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?