In a feverishly polarised political environment, with social media serving up endless incitements to outrage, it is perhaps hardly surprising that even academic debate over some hot-button issues has become highly fractious. The renewed explosion of hostilities in the Middle East has provoked impassioned responses on both sides of the debate, from both academics and students, opening up questions about, among other things, how much activism universities should permit to take place on their campuses.

Meanwhile, perhaps the most fiercely contested front in the so-called culture wars – gender identity – has raised questions about the extent to which concerns about offence and “harm” should curtail academic free speech. In England, concerns about free speech even prompted the previous government to enact legislation to strengthen universities’ duty to protect it – legislation now parked by the new Labour government.

So should academics be able to say whatever they want whenever they want, within the law? Are any restrictions on their ability to do so an unacceptable check on autonomy and knowledge production – or a reasonable and necessary measure to protect the vulnerable? And should there be different rules for students and academics?

To explore the range of views on such topics, Times Higher Education ran an online survey over the summer, which attracted 452 responses from 28 countries. It is important to note that the survey was open to all, and it is likely that those who feel strongly about academic freedom of speech will have been particularly motivated to answer it. Nevertheless, those feelings are evident on both sides of the debate, and the large numbers of responses – with several thousand associated comments – offer at least some insight into the range and nuances of opinion.

The survey had a good response rate across age ranges: 19 per cent of respondents are under 40 (although only 3 per cent are under 30), 30 per cent are between 40 and 49, 35 per cent are between 50 and 59, and 16 per cent over 60. And the differences in perspectives between these age ranges are consistent and often stark.

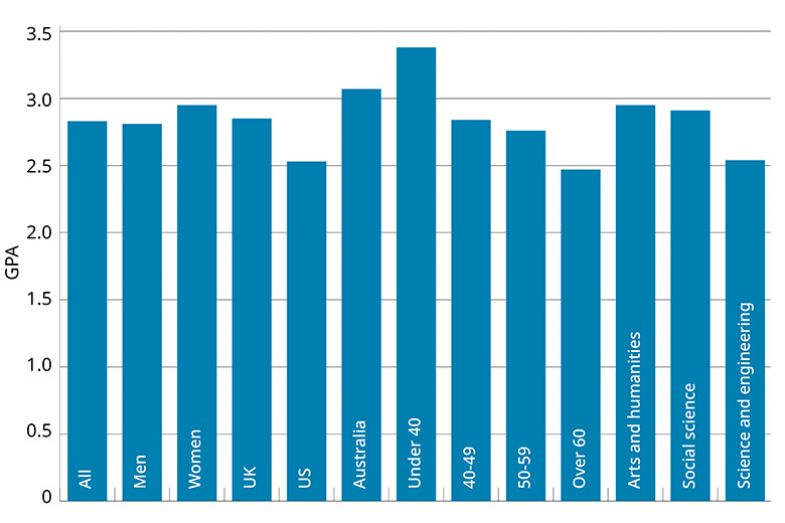

For instance, a startling 88 per cent of over-60s agree that “academics should be allowed to make any lawful statement, in any forum, without censure by their institutions” – 77 per cent of them strongly. When responses on the five-point Likert scale are scored numerically from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), that strength of feeling translates into a grade point average (GPA) of 4.57. Even respondents in the 50-59 age range score considerably lower (4.19), and those in their 40s even lower (4.08). Those under 30 score the lowest – though, at 3.91, even their agreement with the statement might be thought to be surprisingly high. However, that may partly reflect their relatively small, potentially representative number. For that reason, their responses are generally amalgamated into the under-40s category for the purpose of this analysis; the figure for that age range on the issue of full free speech within the law is 4.10.

The other consistent difference throughout the survey is between the perspectives of men and women, with the latter more supportive of restrictions of speech. In this case, women’s GPA is 4.12, compared with 4.23 for men. Just under 40 per cent of respondents identify as female and 46 per cent as male (4 per cent identify as neither and 11 per cent prefer not to say).

A male, UK life scientist over 60 says: “Censorship is the death of free speech and learning. Students (and university institutions) need to understand that one of the essential elements of discovery and progressive thought is disagreement and nuance. Any student (or academic) who wants to ban anything they disagree with is not yet mature enough for higher learning or academia.”

A 60+ UK female life scientist agrees: “Academics and students who cannot hack disagreement and opposing views lead to a regressive and authoritarian atmosphere of censorship where…the university becomes irrelevant and dies…Lively debate and disagreement are the lifeblood of academia and research.”

On the other hand, a US female 60+ life scientist says university provosts “should be able to seriously reprimand or censure or even fire faculty who engage in hateful activities. The unusual power vested in the provost works in academia because it is rare that power is wielded. Instead, people behave reasonably. Unfortunately, we have entered the realm of unreasonableness in some of what faculty are supporting today.”

Campus resource collection: What can universities do to protect academic freedom?

On the question of full-blown free speech without censure, agreement is much lower in the US (3.33) than in the UK (4.27) or Australia (4.36). The vast majority of the respondents (72 per cent) are based in the UK, where controversies over the treatment of the gender-critical academics Kathleen Stock and Jo Phoenix have made the transgender issue particularly salient, while 7 per cent are from the US, the epicentre of controversies over the pro-Palestinian encampments erected on campuses earlier this year. Another 6 per cent are based in Australia, where universities’ responses to the encampments have also been extremely controversial, especially in Sydney.

The range of opinion between disciplines is less consistent through the survey. On the issue of free speech without institutional censure, support is strongest among scientists and engineers (4.41) and weakest among social scientists (4.05). The former group make up 21 per cent of respondents, and the latter 40 per cent. Those from the arts and humanities make up 28 per cent.

Restrictions on free expression

Of course, all issues regarding academic freedom and freedom of expression are highly complex, with numerous contexts to consider, including forum, audience, intention and expertise. The survey attempts to explore some of those nuances, though it is difficult to isolate them entirely in specific questions.

An example of the context-dependence of so many questions around academic freedom of speech is articulated by a male, UK-based arts and humanities professor in his 40s: “It is disingenuous to claim that there should be no barrier to academic freedom within an educational context as it ignores the reality that courses (modules or programmes) exist within a specific context of disciplinary knowledge, concepts and facts. Academics should have the right to put forth their views without censure, but in the context of prescribed courses there must be a requirement to adhere to relevant knowledge and learning...This is not synonymous with censure of ideas or opinions.”

And a New Zealand-based psychotherapy academic in her 50s notes that “Galileo was right to prosecute his ideas of heliocentricity even against the controlling narrative of the Catholic Church because his views were based on a programme of research that was intended to discover deeper realities. However, provocations based on displays of power and attempts to oppress groups or individuals or impose harmful views about others (such as eugenics, sexism and racism) do not merit support in the same way, as they are not reasonably intended to advance knowledge and understanding.”

Another issue in this case is precisely what “censure” might amount to. A UK-based clinical professor in his 50s says: “An institution should be able to say that it does not agree with a statement.” But “academics should be free to make lawful statements without fear of disciplinary or other procedures that have effects on their academic position or employment”.

A UK-based male professor says that “so long as the statement doesn’t directly do, or incite, harm to others then academics and everyone else should be able to say what they want without facing censure from their institutions or from anyone else. If a person thinks biological sex is a more important [criterion] than chosen gender when it comes to protecting women-only spaces then why should the pressure from a lobby with different views make the view censurable? If someone regards the actions of the Israeli government in its war in Gaza as constituting a war crime, why should a lobby be able to claim that that constitutes antisemitism given that it makes no racist claims about Jewishness? Conversely, if someone is outraged at the actions of Hamas at the start of the war, why should this be regarded as anti-Palestine?”

But others insist on stricter limits. A US mathematician in his 50s says that in the US “it’s ‘lawful’ to deny the Holocaust, but an academic who does so (especially after being advised not to) should be disciplined”.

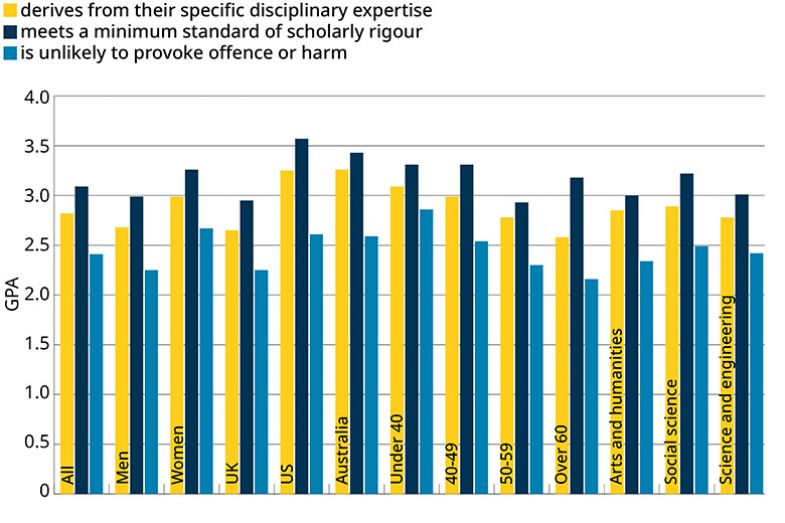

Asked what conditions might be applied to free expression within the law, the most popular answer is that “the speech meets a minimum standard of scholarly rigour” (with an overall GPA of 3.09), followed by “the speech derives from [the speaker’s] specific disciplinary expertise” (2.82).

Academics should be allowed to make any lawful statement, in some or all forums, without censure or punishment by their institutions only when the speech

“Academics (and everyone else) should be able to say anything at all whether others may be offended or not. But academics especially have a responsibility not to make statements that are unsubstantiated and a responsibility to consider possible consequences of public statements,” says a 60+ UK male arts and humanities academic.

“We can’t have our music history professors lecturing our students in class that the Earth is flat. That’s not in their area of expertise,” adds a US senior leader in her 50s.

However, “The problem with the qualifications is: who gets to decide,” adds a 60+ UK social scientist.

The condition that “the speech is unlikely to provoke offence or harm” attracts less support (2.41), with 43 per cent strongly disagreeing with it as a check on free speech. Support for it is particularly low in law (1.92) and physical science (2.17). The offence-harm continuum is a central bone of contention in debates about free speech, which the survey probes in more detail later.

Perceptions of freedom

Do academics feel that their freedom is becoming more restricted? The answer seems to be yes. A full 77 per cent of respondents agree that academic freedom of speech is more restricted in their country than it was 10 years ago. That view is particularly strong in the US (83 per cent) and in psychology and clinical health, when sex and gender issues loom large.

For instance, a UK psychology academic in her 40s perceives “a serious problem in some areas, largely where there is a strongly held position by activists on a topic (gender, colonialism, Israel/Palestine, neurodiversity are some examples) and any diversion from the accepted line is seen as meaning you are a bad person rather than just someone who disagrees”.

Other respondents highlight the rise of bureaucracy around campus speakers. “Ten years ago I did not need permission to invite guest speakers/lecturers for example,” says a UK law professor. “Now, I have to complete a whole external speaker form, await a risk assessment from an unknown source, and receive permission before I am even allowed to invite an external speaker. The risk assessment undertaken includes whether the speaker has publicly spoken on a topic deemed sensitive and taken a position (even where this is lawful) that the university disagrees with.”

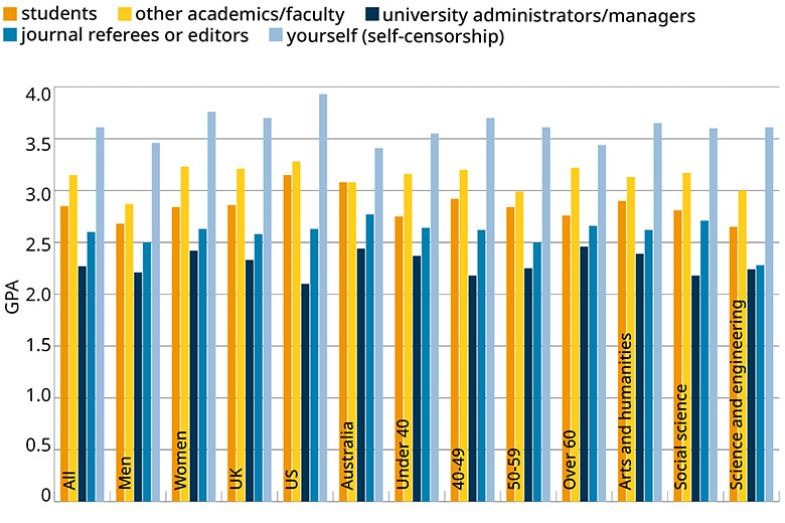

Asked about the specific sources of restriction to their freedom of speech, respondents most frequently point to themselves. Self-censorship is practised by 68 per cent of respondents, rising to 74 per cent of women and 80 per cent of those based in the US.

Your academic freedom (or your freedom of speech as an academic) has been restricted for reasons other than legal ones by

Interestingly, other academics are seen as a greater check on academic freedom (with a GPA of 3.15) than students (2.85). For instance, at one UK university “there is a move to stop all work with ‘fossil fuel’ companies. This is being backed up by violence and driven by senior members of the university. These academics are in the humanities and are targeting the scientists who are actually doing the work to combat climate change. There is real fear and intimidation.”

But students are still criticised. In the view of a UK arts and humanities professor in her 40s, “student consumers now increasingly dictate what they want to hear in lectures and seminars. They have disproportionate power in relation to their knowledge and experience. Student political, religious, and personal beliefs are protected, while an academic’s views and arguments are censored and overridden.”

An over-60 female academic in UK arts and humanities was “labelled a ‘transphobe’ by an anonymous group of students, aided by their student union, and the process was supported by the university via HR. I had to argue my position to (HR) people who knew nothing about the nuance of the debate, and there has been ongoing rumourmongering among students. I am very, very careful now. I am also careful about criticising Hamas, or the Palestinian liberation movement, or suggesting that Israel may have a point. I self-censor now.”

A UK psychologist in her 40s is “careful about discussing issues of sex/gender around students because I don’t want to provoke an argument, and so sometimes I avoid the topic where possible. This is despite the relevance of this area in psychology.”

Perhaps surprisingly, university managers are bottom of the list of checks on academic freedom (2.27). Perceived threats to freedom from managers are highest in Australia (2.44) and lowest in the US (2.10), perhaps due to the tenure system there. But perceived threats from students and other academics are highest in the US.

One UK respondent was “told by a VC that my tweets have been shared among VCs and, at one point, a VC at another institution wrote to my VC demanding I be censored for commenting on redundancies at their institution”.

Another “never directly criticise[s] my institution or its apparatchiks publicly, because of the ‘reputational damage’ rule. I always express my criticisms in general, sector-wide terms. But they are often meant for the morons who run my institution and have done so much to debase it.”

As in the “transphobe” case above, managers also come in for blame for not defending academics against attacks from other groups.

In 2017, one UK computer science professor in her 50s was asked by her institution “to remove a social media post in which I drew an analogy between Brexit and Nazi Germany. This was as a result of somebody tracing me down to my institution and filing a complaint. Rather than support me and defend me as they should have done, [the university implied] that there could be consequences for me if I didn’t remove it. I still hold this against my institution.”

A UK legal academic in his 30s teaches “with as little personality as possible because significant numbers of students find offence in anything that they dislike, and consider themselves harmed by things they disagree with” and he has “no confidence that one would be backed in the event of a complaint about nothing”.

“I have had a nightmare about receiving a complaint arising from my lecturing the facts of a particular judicial decision…about a cow which, according to the parties’ contract, was not supposed to be pregnant, but was pregnant, when sold," he says. "In the nightmare I am not backed by the university even though I essentially relate the facts from the law report itself (the case actually exists) and nobody will listen to my position at all. I think the mentality is pretty engrained.”

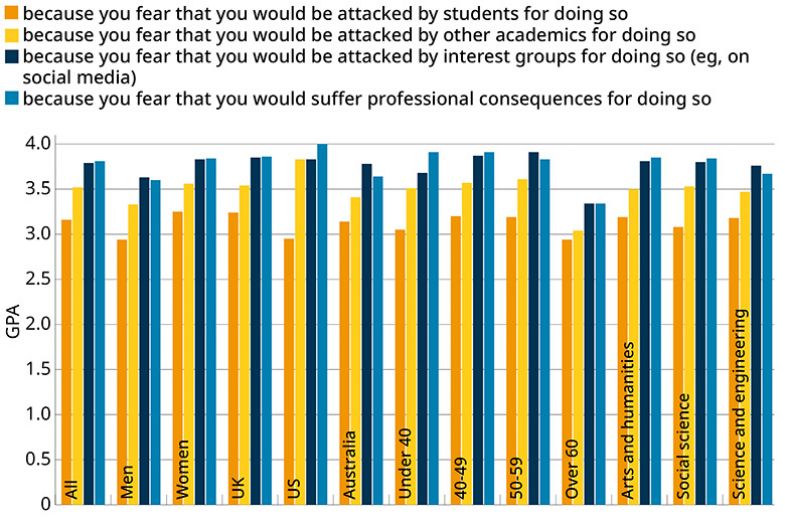

In relation to self-censorship, many academics have some theories or positions they would not publicly question, support or oppose because they fear it would cause offence (3.09) or harm (2.06). Again, fear of being attacked by academics (3.52) is significantly higher than fear of being attacked by students (3.16); interest groups on social media are an even bigger fear (3.79). But the most common reason for self-censorship is fear of suffering professional consequences for doing so, such as being disciplined or being overlooked for a grant or a promotion (3.81).

There are some theories or positions you would not publicly question, support or oppose

“As an academic without a permanent contract, I haven’t experienced any direct interference with my freedom of speech by others. However, I do self-censor in terms of what I say in the public domain because I fear it may harm future job applications,” says a male UK arts and humanities postdoc.

In all cases, women are significantly more likely to self-censor than men are, and the over-60s much less likely than younger age ranges. Psychologists have a particularly strong fear of other academics (4.04), interest groups (4.24) and professional consequences (4.36).

Taking offence

The extent to which academics are likely to police each other’s speech is in part a function of how quick they themselves are to take offence. Asked whether they have “encountered (legal) speech/writing that caused you or someone you know unacceptable offence or harm”, more respondents generally disagree than agree. Interestingly, the most likely cause of offence is university communications (2.52), though even in this case, only 32 per cent of respondents agree that they have been offended. Student essays (2.18) and academic publications (2.17) are the least common sources of offence. Academics in law are especially likely to have been offended, across all categories.

Essays are not the only sources of offence from students, of course. “An Aboriginal colleague of mine had a student go on a right-wing radio show and criticise her course on Aboriginal studies, twice,” says an Australian academic in her 40s. And “antisemitic comments from students (especially Muslim students) are commonplace and often go unchallenged. This creates a hostile atmosphere for Jewish students,” says a UK arts and humanities professor in his 50s.

A UK social scientist in his 50s has “worked at an institution where a men’s rights group (led by an academic) had infiltrated a Christian student society and had radicalised their members. One of whom stood up in a lecture on violence against women and pronounced that his religious views meant that he thought women had no right to bodily autonomy and that rape should not be a criminal offence. This caused a great deal of distress to many of the women in the audience who had experiences of such violence.”

He has also “witnessed a number of ideologically driven and personal attacks aimed at colleagues by other academics who hold more problematic beliefs (especially on racism, trans issues and political economy) get published in academic publications. The issue here has been that editors and reviewers have clearly not understood the attacks” because they lack an “insider perspective”.

More generally, “there is plenty of historical, literary, legal and scientific writing about women, queer people and black people that is offensive, inaccurate and has perpetuated and sustained demeaning attitudes toward these groups of people,” says the New Zealand-based psychotherapist. “That is why challenging conversations need to be had, to evaluate blindspots and advance new understandings.”

Women are more likely to take offence (averaging 2.44 across all categories) than men (2.22), with UK academics being less likely (2.21) to than those in the US (2.33) and Australia (2.67). Younger age groups are generally more likely to take offence, though there is also a marked spike in the 50-59 age range. Scientists (1.86) are particularly unlikely to, while arts and humanities academics are the most likely to (2.53).

A UK legal academic in his 30s notes that he probably has “a high offence threshold – I’m a white able-bodied male so people can pretty much say anything they like and it’ll probably be partially true and yet not particularly likely to change the system that means I get an easy ride”.

A female UK law professor is highly offended by “proponents for censorship, limitations on fundamental human rights (such as the right to protest), the de-sexing of certain crimes/criminals (such as male violence against women and girls) and the positive gendering and de-sexing of single sex spaces, and I believe it…poses specific risks of harm to women and girls. However, I would rather hear/read the legal speech/writing and have the opportunity to challenge it openly and without censure than ban it.”

Similarly, a UK assistant professor has “come across things that I may have found offensive, but that is irrelevant. It is up to me to take on the substance of the view rather than just seek to curtail the person’s right to say it.”

An Australia-based arts and humanities professor over 60 agrees that “we should all tolerate speech and writing that merely offends us, as opposed, say, to inciting violence against us, destroying our reputations, invading our privacy, etc.”

Offence and harm

That last answer takes us towards the fraught issue of when, if ever, offence counts as “harm”. The latter term is often evoked in defences of restriction on speech, particularly to protect certain groups viewed as especially vulnerable. But the extent to which words can cause harm is highly disputed among respondents.

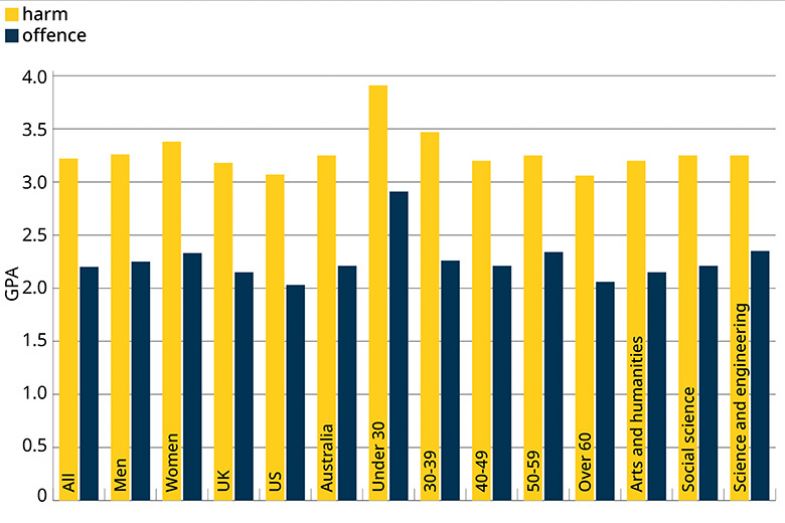

Asked whether offence is a form of harm, only 19 per cent agree, 4 per cent strongly (2.23). Women are markedly more likely to agree (2.46) than men are (2.15), and those in the US (2.37) are more likely to agree than those in Australia (2.25) or the UK (2.06). Agreement generally declines with age, from 2.58 for the under-40s to 2.04 for the over-60s. Agreement is particularly high in education (2.93) and low in law (1.96) and clinical health (1.89).

Some respondents dismiss those who elide offence with harm as “woke”. As an Australia-based business and economics professor in her 50s puts it: “Having a different opinion that might be offensive to overly sensitive woke individuals has led to them claiming harm because their cottonwool upbringing permits them to. Woke people have lost their ability to have resilience to other points of view or lifestyle choices.”

“Harm is invented in order to be weaponised,” agrees a male social science professor over 60. “Offence is gleefully taken. Those claiming harm should be ignored. Those weaponising it should be prevented from causing actual harm.”

A senior UK leader in her 50s “could offend people who believe the world is flat with evidence that it is round – so may harm their personal sense of belief and values. But the evidence is of more value and significance than the upset caused to non-believers.”

Others take a more lexical approach to maintaining the distinction: “Offence is not a form of harm, by definition,” says a UK lawyer in his 30s. “You can be so offended that you keel over with a heart attack [but] the harm you suffer following your taking offence is distinct from your taking offence.” And an Italy-based arts and humanities manager in his 40s suggests the difference is that “harm, physical or psychological, can be measured”.

But others see less of a clear distinction. “I think offence can be harm in some circumstances, depending on the harshness of it,” says a 60+ US life scientist. “I also think that the concept of fighting words can sometimes apply, and so offensive speech or [an] offensive placard might yield violent confrontation. I do think words can hurt.”

A female arts and humanities professor in Australia specifically identifies “speech that refuses a person their human rights (ie, racism, transphobia)” as harmful. And a UK social scientist in his 50s makes a similar point: “Challenging ignorance and assumptions on a topic (such as British Imperial history) may cause offence as it disrupts someone’s ontological/epistemological position, but this is not the same type of offence that exists if stating that a population is less than human, or should not have rights, or exist. The former causes offence, but the latter existential position can cause significant harm.”

And a senior leader in her 40s notes: “If you actually listen to colleagues from under-represented groups, they will explain that it isn’t offence that harms them: it is the repercussions of repeating negative stereotypes and the impact this has on societal views...Many are not offended by people having different views: it’s the threat this creates of increased exclusion and violence by some elements of society.”

A UK 60+ social scientist believes it is “fine to ‘harm’ dominant groups, such as bankers or vice-chancellors, through speech/writing, but not those dominated or oppressed. In other words, power is always a significant consideration. It is difficult to derive general principles when asymmetric power relations are at stake.”

A UK education academic in her 30s is clear that some positions should never be articulated: “We don’t want professors who believe in eugenics spouting off all the time publicly and turning their workplaces into toxic environments of ill repute. There are some opinions that should be kept to themselves, in order for society to function.”

Unsurprisingly, respondents agree that the potential to cause significant harm is a more legitimate check on academic free speech than the potential to cause offence. Only 17 per cent agree that offence ought to silence academics (2.20), rising to 2.35 for under-40s (and 2.91 among under-30s) and falling to 2.06 among over-60s. Perhaps surprisingly, agreement is higher in science (2.35) than in social science (2.21) or arts and humanities (2.15).

The potential to cause significant offence or harm is a legitimate check on academic freedom and/or academic free speech

Asked the same question about harm, 49 per cent agree that it should be a check on speech, 13 per cent strongly (3.22), with similar differences between ages and disciplines. More women than men agree in both cases. But some respondents worry about the lack of a definition of harm: “What counts as harm, and who gets to decide? These are not neutral terms,” says a UK social scientist in her 30s.

In an ideal world, the survey would have handled offence and harm separately, but in order to keep it relatively short, they were generally presented in questions as an either/or, leaving respondents to specify their own differential attitudes towards the concepts where necessary.

One question examines whether there are any conditions under which “academics should suffer professional consequences for speech or writing that causes offence or harm”. Only 3 per cent of respondents opt for “whenever it occurs”, against 29 per cent who say “never”. But most take a more nuanced position: 31 per cent say “only if the harm or offence derived from beliefs, understandings or theories that were not based on reasonable evidence” and the same proportion say “only if the harm or offence was actively sought”.

Many respondents specify that their approval of restrictions on speech applies only in the case of illegal speech or significant harm.

“I think that blatant racism, sexism in language and in actions does need to have consequences,” says an Australia-based arts and humanities academic in her 40s. A UK law academic suggests that consequences should only apply for “calling for the eradication of certain groups by violent means, where ‘violence’ is defined as using physical force capable of causing physical harm”.

However, an Australia-based arts and humanities professor in her 40s cautions that “sometimes causing harm and offence is the morally correct thing to do” – although she does not give any examples.

Contexts

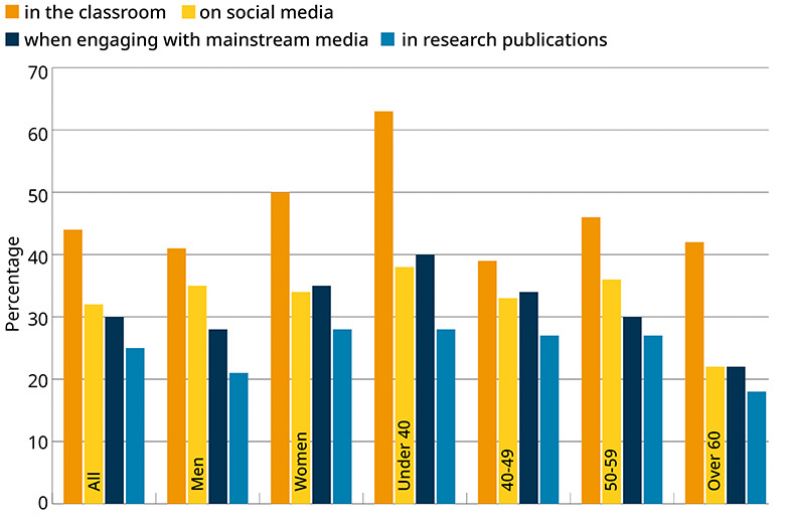

Regarding the specific contexts in which avoiding offence or harm should be mandatory for academics, the classroom receives the strongest assent (44 per cent). But that figure marks a stark gender split, falling to 41 per cent among men and rising to 50 per cent among women. Significantly more women also believe it is important to avoid offence or harm in engagement with the mainstream media and in research publications, but slightly more men than women agree that it is important to do so on social media.

Academics should be obliged to avoid offence

There are also significant age splits, with 63 per cent of under-40s believing it is important to avoid offence or harm in the classroom, compared with 39 per cent of those in their 40s and 42 per cent of over-60s.

Among the last group, a female life scientist notes that “it is very difficult to avoid ‘offence’ if one is teaching a subject (say, biology) which a particular student does not believe in. The lecturer is the expert and should be expected to apply appropriate measures to ensure that the student group as a whole receives accurate information on the subject as it is currently understood. The question should be why is that student on that course and should they not be required to justify their non-belief? There should not be onus on the lecturer to pander to such an extreme outlying view for which there is no evidence.”

A UK clinical health professor in his 40s agrees: “We should try and avoid offence, but there will always be students, academics or just parts of society that have an entrenched view which differs from yours and therefore they will be offended.”

A UK 60+ physical scientist says students “need to show dignity to all at all times. There is far too much taking offence at statements that one disagrees with, even when calmly stated.” And a UK psychologist in his 40s says lecturers should strive only to avoid offence that would be taken “by a ‘reasonable person’…lest one be silenced by the heckler’s veto”.

A UK arts and humanities postdoc says academics should have “a positive duty to promote a respectful, inclusive and constructive dialogue among students in their teaching, but they may not be able to avoid offence if stating their views truthfully on certain issues”.

On the use of gender-neutral pronouns, a UK social scientist in her 30s is very clear that refusal would be unacceptably offensive: “The classroom has to be a safe space for all students and staff,” she says. “This means using correct pronouns. I’ve never had students refuse to do this.”

While the classroom is seen as an important place to avoid offence, it is evident that scholars do not believe that they ought to spare students the possibility of offence in all forums. Just 6 per cent of respondents believe that academics ought to avoid public speech that could cause offence to students generally – and only 7 per cent believe the same regarding their own students. Meanwhile, 69 per cent say that there are no groups of people whom academics ought to avoid offending in their public speech – though, again, there are big gender and age disparities, with that figure rising to 76 and 75 per cent respectively among men and over-60s and falling to 58 and 55 per cent among women and under-40s. Just over 14 per cent of women believe academics should always seek to avoid offence, against 9 per cent of men.

“We should rely on the law. We don’t need extra guard rails,” says a UK arts and humanities manager in their 50s.

But a male UK professor thinks speakers should always “be aware of, and sensitive to, the audience. That doesn’t mean that the speaker can’t say things that might be uncomfortable for the audience but public speaking, as in any conversational setting, should normally avoid gratuitous statements designed to aggravate.”

Students

If the classroom is a key place to avoid offence, that raises the question of whether students should be bound by the same rules as academics regarding harm and offence. Respondents are marginally inclined to believe that they should. Only 39 per cent agree that academics have a greater responsibility to avoid offence or harm than students do, against 43 per cent who disagree (giving a GPA of 2.84). Agreement is highest in Australia (3.07), among the under-40s (2.97) and, perhaps surprisingly, in engineering (4.00). Men are marginally more inclined to agree than women (2.93 v 2.90)

Those that agree with the proposition point to academics’ power over students and the latter’s relative immaturity.

“Academics should know better and be more aware of the impact than students are,” says a US economist in his 50s, while a similarly aged US colleague in mathematics believes academics “should model appropriate speech and behaviour, including how to make a point without resorting to inflammatory rhetoric”.

Even some of those who think the same rules should apply to students and academics concede that – as one UK arts and humanities professor in his 50s put it – “academics have authority in the room that students don’t have so should reflect that in their behaviour, being aware of how power inequalities can shape how words and behaviours are understood”.

A female 60+ arts and humanities professor says: “If we feel we need to offend deliberately to do our jobs, then we might want to do some self-reflection.” On the other hand, “the students are stupidly young and ardent for causes, and they see giving offence as a badge of honour. So don’t give them so much power!”

Should students be obliged to avoid speech or writing that could cause offence to anyone? Only 19 per cent of respondents agree, and just 1 per cent think they should be required to avoid offending academics specifically. Indeed, only 6 per cent believe they should be prevailed upon to avoid offending even their own classmates, rising to 8 per cent among women and 11 per cent among under-40s.

“If a student promotes a baseless view that is harmful in an assignment, the grading criteria should address that (for example, unreferenced unsubstantiated claims receive lower grades),” says the New Zealand-based psychotherapist. “If they do this in a class space, the lecturer can facilitate a process where impacted students can state their case, or, if they feel unsafe to do so in the space, they can lodge a complaint that will be addressed following a published complaints process. It depends on context.”

An Australia-based law professor in her 50s is unsure: “You should see the racist and sexist and ableist comments in student evaluations: terrible, and inappropriate. But in essay-writing or in class, some students simply don’t have the language to be able to express themselves in respectful ways.”

A UK administrator in her 30s even thinks that “displaying potentially offensive views is sometimes a good learning curve for students to understand the reach of offensive opinions”.

Others are adamant that there are no excuses for offensive students. “Students are adults and need to accept the responsibilities of being a member of society,” says a French-based social scientist in their 40s. “Academia is about honing critical thought and reasoning with respect to theory, not attacking individuals.”

Some specifically question whether students should be obliged to avoid offence. “I do think they ought to,” says a UK arts and humanities academic in his 30s. “But I don’t think there should be any kind of penalty beyond that already encoded in, say, honour codes.”

Another fraught issue in the freedom debate is whether student societies should be able to invite anyone to speak on campus regardless of the offence that the speaker might be expected to cause to other members of the campus community. Some societies have invited highly contentious figures, provoking student protests or, in some cases, cancellations of the event by university authorities amid fears about safety. But a full 67 per cent of respondents agree that students should be able to invite who they want, 39 per cent strongly.

“In some cases, speakers might incite violence, attempt to recruit students into paramilitary or terrorist organisations that practise violence,” notes an Australia-based arts and humanities academic in his 60s. “But if we are talking about mere expression of views, on political or philosophical issues, it should be almost unthinkable that this would preclude them from speaking.”

While many comments similarly stress that any speech within the law should be tolerated from external speakers, many others suggest there are limits, both practical and ideological.

“Universities aren’t free-for-alls,” says the New Zealand psychotherapist. “They are supposed to model rigorous thinking rather than shore up individual or group identities. For example, a Muslim student group should be free to invite imams to speak with their group. They ought not to be allowed to invite an imam who preaches fatwa or similar harms.”

A UK social scientist in her 30s thinks “we can all agree that student societies shouldn’t invite Nazis. This may seem like an extreme example, but the point is that we all draw invisible lines in our heads around what is and isn’t acceptable. The challenge is to have more open, earnest conversations about the harm done to communities that are not like our own and to let the most marginalised guide the standards we implement.”

A male 60+ life scientist in the US agrees that there “should be rules” and suggests that universities should establish “a committee of reasonable people to help avoid bringing in those who would espouse hatred”.

What about students’ right to disrupt campus events when speakers are expected to make statements they consider harmful or offensive? While 40 per cent of respondents agree that they are within their rights to do so, 45 per cent disagree, 27 per cent strongly (giving a GPA of 2.83). Support for disruption is markedly higher among under-40s (3.38) and particularly low among over-60s (2.47). It is also lower among men, in the US and in science and engineering.

Students are within their rights to disrupt campus events when one or more speakers are expected to make statements they consider harmful or offensive

But some scientists defend student protest. A UK physical scientist in his 40s says: “Freedom of speech is not freedom of platform, or [from] consequences. There are people peddling hate for their own benefit. Students have a right to protest that someone should not be provided a platform at their institution. That is not censorship.”

Some respondents stress that disruption is only acceptable when the speaker is likely to cause harm, rather than mere offence. Others say that while protest is fine, seeking to shut down the event is not. “Students and others have gone beyond what is acceptable – attacking speakers and visitors, blocking entrances, verbally abusing staff,” says a female senior leader in the UK. “Universities are now suffering because they have been unwilling to defend the right of speakers to attend safely.”

Exclusions and boycotts

Returning to the classroom issue, respondents are clear that even if it is particularly important for academics to avoid offence in the classroom, they should not be able to exclude students with offensive views; only 16 per cent agree that they should be able to exclude students even when their views are considered offensive or harmful by the majority of the class, and only 4 per cent think a single student should have a veto on one of their peers – though a UK arts and humanities professor in his 50s makes an exception for “directed hate. Then just one student is enough.”

Others specify, again, that harm might be an acceptable condition, while offence is not. A version of that view is expressed by a UK educationalist in his 50s, who believes students should not be barred “unless the individual is actively seeking to make the classroom unsafe for other students (rather than them just believing they might be unsafe)”.

A 60+ UK computer scientist who does not identify as male or female believes that a student should be barred only if they are expressing views that are “irrelevant to what is being taught and, hence, a distraction from legitimate classroom discussion”.

Others take a more institutionalist approach, saying academics should simply enforce the behavioural expectations outlined in syllabi or departmental regulations.

If academics should rarely be allowed to bar students, most respondents also think students should not be able to opt out of classes or seminars taught by academics who have said or written anything they deem offensive or harmful. Only 9 per cent believe this should be possible even if the majority of the class object to the academic’s utterances – although 25 per cent make an exception for students who feel personally offended or harmed.

Some respondents point to the impracticality of allowing students to opt out of core modules. But others think it should be made possible: “Students should be able to set their timetable and have options for required courses,” says a 60+ female education professor in Canada.

A male 60+ arts and humanities academic in the UK believes “students should have to attend their course unless the lecturer is deliberately offensive: ie, rude.” And a UK social scientist in her 50s believes that even when offence or harm occurs, the first resort should not be student boycotts but complaints to the academic’s line manager, who could then warn the academic to “change their behaviour” and require them to attend “appropriate training if needed”.

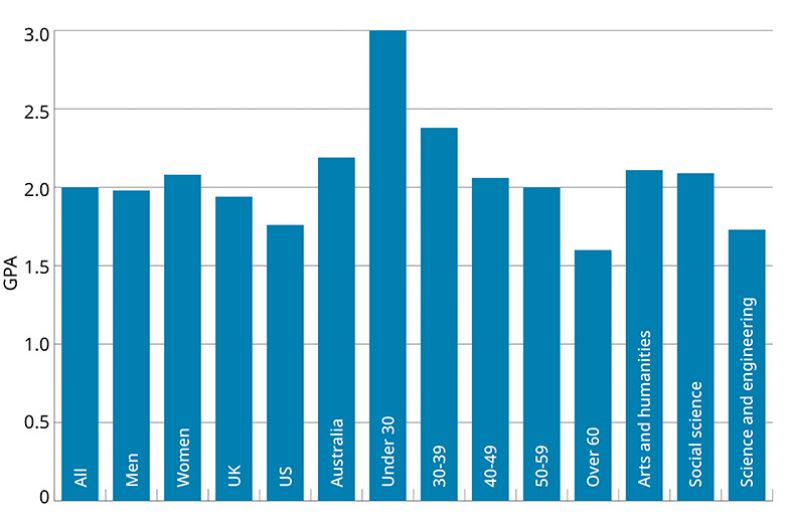

Respondents are similarly unsympathetic to the idea of students actively disrupting the classes of academics whose views they deem offensive or harmful. Just 17 per cent deem this acceptable, against 72 per cent who disagree (2.00). But there are marked age splits. Among under-40s, the GPA is 2.47 (and 3.00 among under-30s), falling steadily to 1.60 among over-60s. Men and US respondents are also particularly disinclined to consider disruption acceptable.

Students ought to be permitted to disrupt the classes of academics whose views they deem offensive and/or harmful

“Generally speaking, I would say that it is very disrespectful of students to disrupt a class and prevent other students from taking that class,” says a female 60+ UK life scientist. The correct course of actions would be “to contact the lecturer to discuss this privately and to explain why they found it offensive. I would expect an academic to allow for discussion of contentious issues if class size permits but also to shut it down if such discourse becomes disruptive for the learning of other students.”

A UK senior leader in her 40s says students should “express opposing views in a reasoned, tolerant and inclusive way – disruption is not an appropriate response to something you don’t like. To me, it smacks of not having the ability to argue your case.”

Others are more sympathetic, even if they remain uneasy: “Students can disrupt, but to do so is to impose a decision – and consequence – on students who do not share their views and who wish to learn,” says a UK social science professor in his 50s.

“Protest is important [and] it needs to cost someone something to be effective,” says a 40+ arts and humanities academic in Australia. “Civil disobedience is fine, and usually passes quickly.”

And while a UK arts and humanities academic in his 30s is largely opposed to student boycotts, his reason is that it might put the protesting student “in danger”. The university “should be doing more to support the student’s ability to air their views in a safer forum”, he adds.

Academic freedom

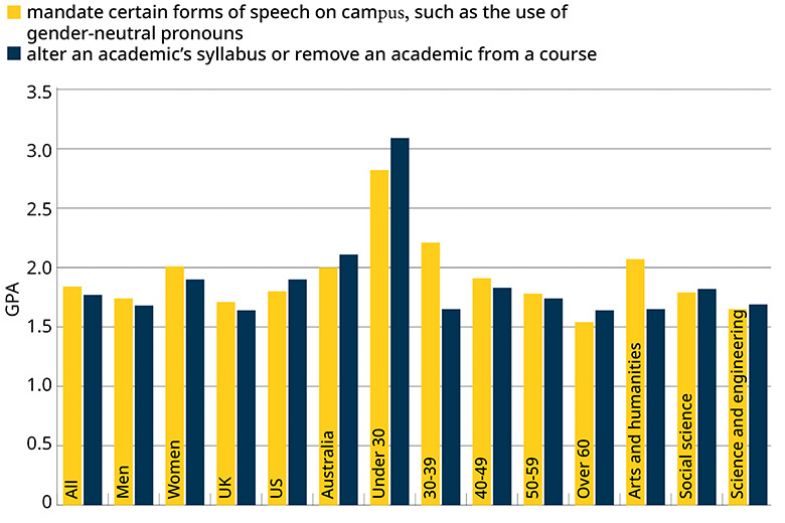

Academic freedom in its narrow sense is often depicted as freedom from administrative interference in academic affairs – and respondents are fiercely protective of it. Asked whether “university managers/administrators should have the right to alter an academic’s syllabus or remove an academic from a course if they consider it necessary to avoid students being offended or harmed”, only 12 per cent agree, 2 per cent strongly. Men, the over-60s and respondents in the UK are particularly likely to disagree.

However, there are some caveats. These include when the teacher “promotes hate” or is “teaching creationism, against the evidence”, which is “harming students’ learning and not in alignment with university mandates about critical thinking”.

“The embittered academic who wants to provoke students by asking them to watch porn: that should be prevented,” says a UK arts and humanities academic in his 50s. “But academic study should be challenging and that might mean encountering materials that are distressing and offensive. Students need to be protected by being prepared appropriately for those materials, but it’s not up to managers and administrators to meddle where they are not experts.”

But a UK senior leader in their 50s argues that “a syllabus should not be owned by an individual” and a UK economist in her 30s believes that concerns about an academic’s suitability to teach a course “should be decided by a committee or panel after thorough discussion and challenge”.

A UK educationalist asks what the point of managers would be if they could not intervene in teaching. “They are there to make sure everything runs smoothly and students have a supportive learning environment. If they can’t protect students from genuine harm (not offence!) then they are toothless.”

But there is some concern that control can go too far. One UK arts and humanities professor in his 50s is, in principle, supportive of management’s right to intervene in teaching, which he considers to be time-honoured. “But I think control of the curriculum is now not exceptional but normalised, such as through demands for ‘decolonisation’,” he adds.

There is also concern about the prospect of university managers mandating certain forms of speech, such as the use of gender-neutral pronouns, when they consider that necessary to reduce the potential for offence or harm. Only 14 per cent of respondents agree that they should have this right, though women (2.01) are considerably more likely than men (1.74) to support it, and those in Australia (2.00) are more likely to than those in the UK (1.71).

If they consider it necessary to avoid offence or harm, university managers/administrators should have the right to

“This behaviour should be banned,” says a 60+ male UK social scientist. “Any university official doing this should be fired, any university allowing this heavily sanctioned.” A UK social science PhD candidate in their 40s agrees: “This is imposing a contested ideology on others.” And a UK lawyer describes the promotion of gender-neutral pronouns as “authoritarian nonsense that should be either mocked or disregarded”.

Others take a more nuanced view. “I myself am queer and I don’t like using gender pronouns to introduce myself because it makes me feel like I have to lie about who I really am, or to out myself if I’m not comfortable,” says a US PhD candidate in his 40s. “I’m happy for others to do so if they’re comfortable.”

A Norway-based arts and humanities academic in her 40s suggests that “universities should mandate that academics, other staff, and students use non-discriminatory speech but not necessarily require the avoidance of gendered pronouns (unless their use promotes harmful stereotypes).”

A UK physical scientist in his 40s says the key issue is to crack down on intentional offence. “Remembering who has gender-neutral pronouns, especially with a lot of students, can be difficult,” he says, so mistakes are “excusable”. However, “staff knowingly and intentionally using a term of address that a student finds offensive, with the intention to cause offence – well, that’s something that should be avoided.”

This issue of civility is an important one. Many defences of academic freedom come with caveats about the need for civility to be maintained. But should it be mandated? Asked whether universities should hold academics and students to standards of civility that go beyond legal obligations to avoid harassment and discrimination, 39 per cent of respondents agree, against 44 per cent who disagree (2.80). Agreement is highest among women (2.90), those based in the US (3.27) and those in education (3.34). Interestingly, while agreement is high among under-30s (3.82), the overall score for the under-40s and over-60s is the same (2.96).

“Kindness matters,” says a UK female 60+ social scientist. “No one can learn effectively when scared.”

A senior UK leader in her 40s adds: “Everyone in a university community should be accountable for their actions and ability to treat others with dignity and respect. Why would we want to create a corner of society where these rules didn’t apply? In any other company, colleagues would be expected to comply with company policy, so why not in a university?”

Some point out that university codes of conduct already uncontroversially mandate civility. And a UK senior leader in her 40s sees this as particularly relevant to the way academics interact with professional staff, noting that “the hierarchy within universities between academic and non-academic staff often creates an unhelpful and toxic culture.”

But others see devils in the details. A gender-critical UK arts and humanities professor in her 50s says: “Someone may think I am going beyond civility if I refuse to use female pronouns when referring to a man, but it is within the law and I refuse to lie. Should I be censured or forced to lie?”

A 60+ male arts and humanities academic in Australia believes that “universities should teach an ethics of discussion, where discussants avoid personal attacks, try to see the possible strengths in their opponents’ arguments, and stick with the evidence and logic of whatever is under debate”. However, “this should not be done coercively. Moreover, there are some situations where you really can’t meet a high standard of civility if you’re confronted with arguments that are simply illogical, poorly evidenced, or worse.”

University managers

Another frequent bone of contention regarding academic freedom is whether academics should be free to publicly criticise their own institutions. Asked whether they should be allowed to do so without career consequences, an overwhelming 87 per cent agree, 63 per cent strongly (4.43). Even among senior leaders, agreement is high, at 81 per cent. The biggest split is between men (4.54) and women (4.26).

“Academia is founded on principles of criticism,” says a 40+ engineer in Canada. “If managers and administrators cannot accept this, they should not be in their role.”

A UK arts and humanities academic in his 50s says, “It has become commonplace for universities to punish academics who criticise them or who express views that potentially cause ‘reputational damage’ (which means little more than that senior managers find them inconvenient or embarrassing). This matter is central to the idea of academic freedom.”

But others are less sure. “Academics should be allowed to [criticise their institutions], but as responsible adults they should also realise there might be consequences,” says a UK arts and humanities professor in his 40s.

And a UK middle manager in her 50s disputes the idea that academic freedom is “about the criticism of one’s employer. That would count as bringing the organisation into disrepute. Disagreements with one’s employer should be handled through normal channels, such as unions and management.”

Finally, there is the issue of whether university leaders themselves should enjoy freedom of speech. Asked whether they should be able to publicly express their personal views on contested topics, 31 per cent say they always should, but 55 per cent stipulate that they should only do so in a personal capacity, making clear that they are not speaking for the university, and 12 per cent say they should only do so when they are drawing on their own specific research expertise.

Only 6 per cent endorse the proviso that the views in question “are unlikely to be considered offensive or harmful by any particular group”. And, interestingly, only 20 per cent of senior leaders themselves believe they should always be free to say what they want in public: a proportion 11 percentage points lower than for respondents more broadly.

"Contested topics require insight, evidence and debate to further understanding, and a wise leader needs to appreciate the risks and ethics of their influential position when participating in discussions on contested topics," says a UK senior leader in her 50s.

A male, 60+ arts and humanities academic in Australia agrees: “Universities are forums for opinion on contested topics and should not have official corporate opinions of their own on these topics. When university leaders express opinions on these topics it starts to get very close to creating a corporate view…I’d prefer that university leaders think carefully before they express their views on these contentious topics at all, as it can be intimidatory and chill expression of contrary viewpoints by their staff, but that doesn’t mean I want it to be outright banned.”

Others are less clear that distinctions between personal and corporate views can always be drawn. “Everyone has personal views, and those views are not separable from one’s professional work in most circumstances. Better to be honest about those views than to pretend they don’t exist or play at objectivity,” says a UK social scientist in her 30s.

A UK arts and humanities academic in his 50s goes further: “Sometimes you have to call a racist a dick. You shouldn’t have to say, ‘Speaking as a private individual and not a representative of the University of Somewhere, you’re a dick’ or ‘Based on my assessment of the state of current academic thinking, you’re a dick’.”

It seems that there are almost as many views on the precise parameters of academic freedom of speech as there are academics. Everyone has difficult judgements to make over what exactly it is acceptable to say in different contexts. But if any profession is equipped to make thoughtful, nuanced appraisals of each context, it surely ought to be academics.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?