Of all the financial meltdowns that are occurring across UK higher education at the moment, the University of Dundee’s is perhaps the most jaw-dropping.

Facing a £35 million deficit, the university is slashing more than 600 jobs, with compulsory redundancies highly likely. On top of vacancies unfilled during a hiring freeze in place since November, that could mean that 870 of 3,200 positions at the university – more than a quarter – could disappear, according to the local branch of the University and College Union.

The Scottish government has sought to steady the ship by injecting £25 million into a scheme “to assist universities such as Dundee with navigating immediate financial challenges”. But Dundee’s acting chair of court, Tricia Bey, admitted to MSPs last week that the university still faces a “very grave cash crisis” and “could become insolvent”.

Questions have been raised over the financial decisions made by the university, but it has also been one of the biggest victims of a long-term dearth of funding – one that may be seen to call into question the sustainability of Scotland’s fees-free policy.

Not that the politicians want to talk about that. Soon after coming to power in 2007, the Scottish National Party (SNP) abolished the £2,289 “graduate endowment fee” with which the previous Labour/Liberal Democrat administration had replaced the UK-wide top-up fees following devolution in 1999. And so committed has the party been to its fee-free policy that its then leader, Alex Salmond, used his last day as first minister in 2014 to unveil a since-removed boulder at Edinburgh’s Heriot-Watt University that bears a quote of his from 2011: “The rocks will melt with the sun before I allow tuition fees to be imposed on Scotland’s students”.

As despite previous Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale’s apparent openness to reviewing the party’s own fee-free policy, her successor, Anas Sarwar, last month made an “iron clad” commitment to retain the “successes of devolution” ahead of what is set to be one of the most fiercely contested Scottish parliament elections in recent years. “Protecting free university tuition” was top of his list.

Hence, all of the major parties will go into the May 2026 poll pledging to leave unchanged what Lucy Hunter Blackburn, formerly one of the most senior civil servants covering higher education in the Scottish government, calls Scotland’s “solidified political climate” on university funding, meaning it will probably prevail at least until the following election, scheduled for 2031.

The omerta on suggesting university funding reform was quickly brought home to Craig Mahoney when he became vice-chancellor of the University of the West of Scotland in 2013.

“I came to Scotland from the English sector, where there is a practice of open dialogue,” he said, noting the successive reviews of English funding policy. “I initially approached my role with the same mindset and, early on, I expressed concerns about the funding model, suggesting a review was needed because it wasn’t sustainable.

"This led to a significant level of public and political scrutiny. My comments were addressed in parliamentary discussions, and there was considerable media attention. I was subsequently advised to be mindful of my public statements and I felt I needed to be careful otherwise I’d find myself losing my job.”

Yet Scottish universities are struggling more than ever. In addition to Dundee’s travails, the University of Edinburgh – long regarded as one of the most successful and stable universities in Scotland – is trimming £140 million from its annual costs through job cuts. The University of Aberdeen last year admitted its future had been in “significant doubt” before it reduced its costs by £18.5 million. Almost all of the country’s 19 universities are included in a University and College Union list of recent cutbacks, and further announcements have been predicted.

Each institution’s troubles have their own unique set of causes, but underpinning them all is a funding system that all sides admit isn’t working well. For its detractors, the system has become a boulder around the necks of both the government and universities, and students should be asked to chip into it through top-up fees or graduate contributions. For its supporters, however, the fix is much simpler: more public money, perhaps combined with an effort by universities to grow other income-generating activities.

Of course, longstanding political reluctance to raise tuition fees even with inflation, on top of the recent crackdown on international students, means that universities in England and Wales, too, are struggling to keep their heads above water. But they remain better funded than their Scottish counterparts. The deficit varies depending on the figures used, but most estimates put it at between 20 and 25 per cent.

Scottish universities receive about £7,610 in funding per student on average, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated in 2023, split between the £1,820 “fee” – fully covered by the government – and a teaching grant, whose value depends on how expensive a subject is to deliver. That compares with tuition fees of £9,250 – soon to be £9,535 – south of the border.

The Scottish fee has never been uprated by inflation, while the teaching grant has been cut back in real terms substantially. The IFS calculates that per-student funding has declined by 22 per cent since 2013-14, with more than half of this decline occurring in the past three years.

Mahoney said during his time, UWS received, on average, £6,500 per student from the Scottish government, amounting to a shortfall of around £43 million compared with a similarly sized university in England. Public funding represented approximately one-third of the institution’s overall turnover.

But while Scottish universities receive less than their English counterparts, the system costs the public purse far more. Per-student public investment is approximately five times higher in Scotland than in England, a London Economics report published last year found. Public sources contribute only 16 per cent of the total cost of higher education provision in England, compared with 113 per cent in Scotland, taking student grants into account.

“There is quite a significant funding gap baked into the system,” said Gavan Conlon, co-head of the education and labour market teams at the consultancy firm. “Despite the Scottish government spending a lot of resource, institutions are underfunded. That is a policy decision; resources are targeted towards students and not institutions. In England it is the other way round,” with students paying for their own tuition via public loans.

Yet while that funding deficit has always been there, recent developments really pile on the pressures, said Hunter Blackburn, who now works as a freelance researcher. “It feels like something is shifting – there’s a sense that we are hitting a point where we can’t go on in the way we have done, and I think that’s real.”

As well as facing falling funding per student, some universities are also struggling to retain their enrolment numbers. One reason is the fall in European Union students, from 20,000 pre-Brexit – when they paid no fees – to 2,000 now they are classed as international students. Dundee and UWS are among the institutions not to have hit their recruitment caps as a result, requiring them to return millions of pounds in teaching grants to the Scottish Funding Council (SFC).

Nor do demographics offer much hope of salvation: school-leaver numbers are set to decrease from 2030 and stay down for some time.

In this context, Scottish universities have relied more heavily than their English peers on international students to cross-subsidise domestic peers. They have therefore been hit particularly hard by the downturn in overseas enrolments fuelled by uncertainties over post-study visa settings and the Westminster government’s dependants ban.

The number of English students studying in Scotland – valuable because they pay English-level fees – has also stagnated in recent years, falling from 29,520 in 2020-21 to 28,885 in 2022-23, although it remains three times higher than the 10,000 or so Scottish students who go in the other direction (who must also pay English-level fees).

Edinburgh also blames a surge in costs for its own troubles, while the coming rise in national insurance payments that employers must pay is only adding to the difficulties.

Scotland’s more managed system gives universities less wiggle room than their English counterparts to absorb the unexpected shocks that have assailed them in abundance over recent years, said Claire McPherson, director of Universities Scotland.

And, for Alison Payne, research director at the thinktank Reform Scotland, all this means that if the current UK-wide crisis does – as is widely predicted – topple an institution, it is most likely to be one in Scotland.

“Our fear is that if nothing changes in the 2026 election, if politicians keep their head in the sand until 2031, then a university will go to the wall,” she said.

More widely, Hunter Blackburn said persevering with the current funding model would result in a slow decline of Scottish institutions, manifested particularly in the “grottification of our campuses”.

“A lot hinges on whether universities can manage to limp on for another three or four years with the effects hidden enough to mean the political bubble [around the fees-free system] doesn’t burst yet,” she said – warning that vice-chancellors may prove to be their own worst enemies if they find ways to make the current system work without fully confronting its unsustainability.

Scottish universities have long become adept at finding ways to cope with a less generous funding regime, noted Mahoney, and the sector is already looking at possible options.

Scotland’s need for more skilled workers has made it less hostile than England to immigration, leading to calls for a more generous graduate visa offer for students at Scottish universities in order to boost enrolment. The idea is backed by the Scottish government but has so far been blocked by Westminster, which retains power over immigration.

Some see a partial answer in strengthening the leadership and governance of universities to allow them to better recognise issues as they develop. Dundee, in particular, has faced questions over how exactly it has found itself so badly off, with allegations of overspending by the previous principal, Iain Gillespie, who quit with immediate effect in December. Politicians have hinted at possible regulatory changes as a result of the Dundee debacle, including greater oversight powers for the SFC.

The SNP government has also come up with some extra money for universities, including £5.8 million to cover extra costs for staff enrolled in the expensive Teachers’ Pension Scheme, as well as the £25 million emergency grant scheme. And the last Scottish budget increased the teaching resource by slightly more than the amount by which English fees are going up.

However, this was largely because a Covid-era increase was unexpectedly maintained even though domestic enrolments have returned to normal levels after spiking when the scrapping of exams required admissions tutors to rely on more generous teacher-predicted grades. And Universities Scotland said that the budget settlement still amounted to a 0.7 per cent real-terms cut.

Future funding levels are unknown since budgets are set annually, making planning difficult. And although Scotland will benefit from increased public spending in England via the Barnett formula, spending more on higher education would inevitably eat into budget allocated for other public spending areas.

Scotland’s higher education minister, Graeme Dey, told Times Higher Education: “Ministers listened closely to the sector in the development of this year’s budget, and we are investing over £1.1 billion in university teaching and research in 2025-26. There are a number of factors impacting universities, including UK government migration policies and the increase to employer national insurance contributions, which is estimated to cost Scottish universities over £48 million.”

Public support for the current funding model remains strong. NUS Scotland president Sai Shraddha S. Viswanathan, who herself came to Scotland as a fee-paying international student, said tuition fees were “an unfair barrier to education, which prevent or scare away the most disadvantaged from pursuing life-changing education…The answer to the crisis in university finances is greater public funding in education, as is common across most of Europe.”

Universities Scotland’s McPherson agreed that “it is not the case that the free tuition model is broken: it is about the level of investment that comes in”.

However, she added, a more subtle debate is needed: “One of the challenges we’ve had in Scotland in recent years is that when there have been attempts to instigate a conversation about future funding, it very quickly falls into a very binary fee versus free discussion, which is hugely unhelpful. We don’t want that to be the focus of the conversation.”

Instead, she said the country must consider what it wants from its higher education system – especially in the context of future skills needs, changing demographics and new models of learning beyond the four-year degree.

“Rather than say we want free or we want fees, we need to consider the outputs and then the question the politicians need to ask is how do we fund that,” McPherson said. “At the moment, there is a strong desire to fund it through public investment. But we need to be clear-eyed about what would be required to deliver the outcomes that we want the system to achieve.”

Introducing top-up fees is the one obvious remedy to the current malaise that is in the gift of the Scottish government alone. And, politics aside, it would be relatively easy to implement, noted Hunter Blackburn.

“You can’t conjure up more foreign students,” she said. “You can’t suddenly create business investment in research and development. But you could…think about at least asking some of those from better-off backgrounds to incur some level of debt in relation to their teaching costs.”

If Scotland replicated the English fee system – which has some of the highest fees in the world – the London Economics analysis found that it would save the public purse approximately £554 million a year. At the same time, it would increase income for Scottish providers by £416 million per cohort, even assuming a likely corresponding decrease in the teaching grant.

Conlon said that some of the money saved could be channelled back into much more generous and targeted student maintenance grants and loans, as it was in Wales when the principality raised tuition fees from £3,900 to £9,000 following 2016’s Diamond Review.

Mahoney said a return to the top-up fee model could be considered, with the per-student contribution being uprated from the current nominal £1,820 to a modern equivalent figure of between £2,500 and £3,000.

For her part, Reform Scotland’s Payne said she favoured a graduate payment, triggered when a graduate earns above a certain salary. This would maintain higher education that is free at the point of use.

All such ideas remain academic, however, as there are no signs of any Scottish politician being willing to touch what Conlon calls a political “third rail”.

After recording its best result in a general election in Scotland since it was decimated in 2015, Labour had set its sights on unseating the SNP at Holyrood for the first time since 2007, but the nationalists have recently been regaining ground. Calling for Scottish students to incur thousands of pounds of debt is unlikely to be considered a vote-winner.

Yet if Labour did win, the party would find itself in the odd position of opposing fees in Scotland while raising them further in England, with Westminster widely expected to commit to future rises that would take fees above £10,000. That tension is, of course, longstanding, but Payne believes that, under Sarkar and Keir Starmer, there is a lot less divergence between Scottish Labour and UK Labour as a whole than there was previously, so it will be “interesting to see what happens” around the university funding question.

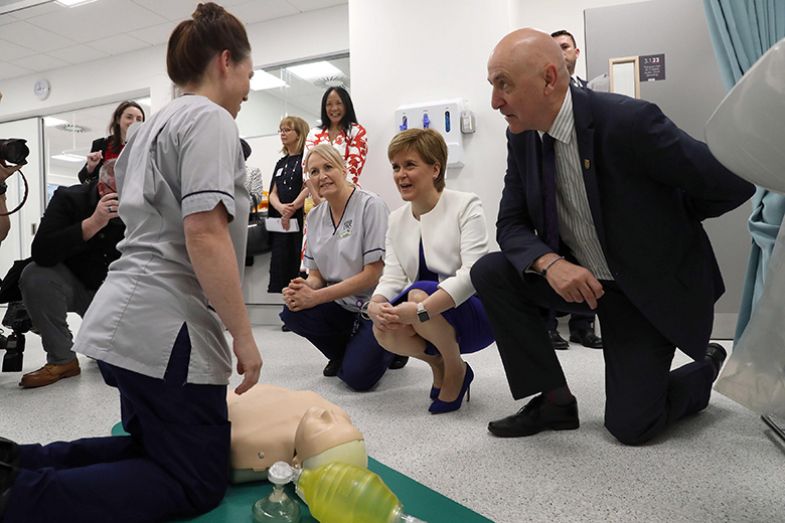

As for the SNP, the 2026 election will see the departures of some long-serving big beasts, most notably Salmond’s successor as first minister, Nicola Sturgeon – who has described scrapping fees as one of the SNP’s “proudest achievements”. However, any expectation that that might open up some space for debate is likely to be dashed as long as another of those figures, John Swinney, remains SNP leader.

University leaders are certainly not sensing a change in the wind direction and continue to keep their heads down; several current rectors and vice-chancellors declined to be interviewed for this article.

As Hunter Blackburn notes, “Even now, when there are real signs that this perfect storm means universities cannot carry on as they are, this one bit of the system is still seen as untouchable.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?