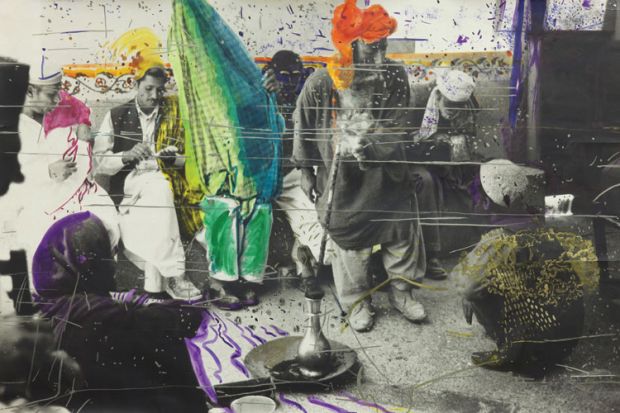

Source: Untitled (Quetta, Pakistan) 1974-1978

Alibis: Sigmar Polke 1963-2010

Tate Modern, London

9 October 2014-8 February 2015

Cultural and political critique rarely makes me laugh out loud. But then cultural and political critique rarely involves performing monkeys, interactions with turkey basters, levitating scissors or telepathic communications with William Blake. Such antics – and many more – are on display in a major retrospective of the work of German artist Sigmar Polke, which opens this week at Tate Modern. First shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York earlier this year, this exhibition showcases the extraordinary range of materials that Polke worked with during his 50-year career (he died in 2010), including meteor dust, snail juice, bubble wrap, soot, children’s duvets, pink fake fur and potatoes. This madcap exuberance is genuinely hilarious, but it is simultaneously a deadly serious and fascinating exploration of perception and propaganda.

Born in Silesia in 1941, Polke fled west with his family, first to Thuringia and then to Düsseldorf, where he enrolled at the art academy and met his long-term friend and rival Gerhard Richter, who had just defected from East Germany. Familiar with the imagery of Socialist Realism, Richter and Polke regarded Western culture’s attempts to disavow its own propagandist tendencies with irony. If Socialist Realism presented the fiction that Soviet citizens had achieved authentic personal and political fulfilment – through feeding geese, say, or driving a tractor – Polke and Richter coined the term “Capitalist Realism” to satirise the implicit claims of Western newspapers, magazines and billboards to represent the world as it really is. Instead, as these artists made abundantly clear, Western culture was saturated with mediation: the glossy yet opaque distortions of marketing, spin and PR.

Inspired by Warhol’s silkscreens, Richter employed his characteristic blur to indicate that his newspaper or photographic source images were themselves mediated (an exhibition of Richter’s work opens at the Marian Goodman Gallery in London on 14 October). Less austere than Richter, Polke made his iridescent, lacquered paintings resemble printed images close-up by adding Ben-Day dots, or “raster” dots as he called them (“raster” is German for “screen”). Distinguishing his approach from Pop Art’s celebration of mass production, Polke painted his dots painstakingly by hand. They focus attention on the surface of the painting, obscuring its content, and produce a dizzying, disorienting visual effect. Yet Polke’s screening and layering effects paradoxically produce the impression of depth: when developing photographs he folded them in half while still wet to produce blotchy Rorschach patterns, inducing and then frustrating a desire for interpretation.

Polke turns on its head the notion of painting as a window on to the world. Half the canvas of To See Things as They Are (Die Dinge sehen wie sie sind, 1991) has been painted with resin, rendering it transparent and revealing the stretcher bars behind the painting that hold the whole thing together. The artwork’s construction is exposed. The title, taken from a newspaper headline, is written back to front and partly obscured by cheap patterned fabric that covers the other half of the canvas. Above the text there’s a scribble of boxes in one-point perspective: the illusion of three-dimensional space that underpins Western art. The illusion of perspective is centred on the individual observer, constructing the eye as the vanishing point of the world. Explicitly citing Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle, Polke is determined to undermine this notion of a stable, fixed self (the exhibition’s title is Alibis). As well as exploring the effects of drugs and Buddhist decentring techniques, Polke painted himself as an astronaut, a palm tree and a powdered drug, and performance films depict him standing in a basin of water with cucumbers floating around his feet, and impersonating a particle orbiting a shopping centre and pressing up against the Berlin Wall.

Seeing things as they really are is also, specifically, capitalism’s alibi: the cultural critic Mark Fisher, who borrowed the term Capitalist Realism for the title of his 2009 book, defines it as “the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent political alternative to it”. Polke’s East German background enables him to see this limiting perspective as subjective. He has a sharp eye for how Western consumerism conjures the allure of escapism and domestic bliss, but then collapses these aspirations into the humdrum paraphernalia of aeroplane meals and washing machines. Polke juxtaposes the hedonistic exoticism of Western culture – its foreign travel, pornography and intoxication – with its bathetic banality: visitors to this exhibition are greeted with paintings of Tupperware, socks, biscuits and sausages. But far from being a detached observer, Polke immerses himself not just in imagery but in experimentation with hallucinogens and trips to Afghanistan, and there’s a joyfulness about his engagement with kitchen implements and vegetables.

Polke tries everything, and sends everything up, and undermines every fixed position. His luxuriant paintings of palm trees and lumps of gold are a riposte to Soviet drabness. Referencing the Nazi preoccupation with purity, he embraces contamination and corruption, smearing arsenic over his gold and exploring the photographic effects of radioactive uranium. He paints with silver sulphate that fades over time, and makes a virtue of photocopying glitches, producing ghostly, warped images. The Nazis banned Modernism so he adopts Constructivism for a while, but then sneaks swastikas into its clean lines to sully Germany’s pious repudiation of its past – as well as suggesting a parallel between idealistic and dangerous abstractions.

While Polke’s work exposes, therefore, the concealments and pretensions of his – and, to some extent, our – time, it defiantly resists reduction to topical commentary or easily legible diagnosis. As an artist, Polke was at once profligately open to influence and occultly indecipherable. He was stubbornly elusive, burying his telephone in a suitcase and refusing to admit visitors to his studio. He often worked in his library, which contained tens of thousands of books: on the philosophy of Martin Heidegger, Edmund Husserl and Jean Baudrillard; on interior design and Photoshop; and also, emblematically, on Kabbalah, that most impenetrable of intellectual systems. He pasted clippings from newspapers and magazines into scrapbooks every day: his prolific collages are Post-Modern without being facile or nihilistic.

Asked in 1966 why he used images drawn from the surrounding culture, Polke replied: “Maybe I want to show how dependent we are on existing forms, how unfree our thoughts and actions are and that we are continually resorting to what exists, or that we are in fact obliged to do so, consciously or unconsciously…It can also be irony, laziness, incapacity or dullness. But it can also epitomise creative freedom: the freedom of doing what one wants to do and what one thinks is right to do, which could be imitating something.” This wilfully inconsistent explanation exemplifies Polke’s tricksterish approach. It also suggests why Capitalist Realism – in Polke’s hands – is not incapacitating: he sees how Western “freedom” is undermined by unacknowledged conformity and conditioning, but he also sees that adopting Western culture at all is a choice.

Polke’s art can sometimes resemble the mash-ups and montages of the purportedly post-political digital age – riffing as it does on communism, Nazism and capitalism, Leonardo da Vinci, Gauguin and Malevich. But it manages not to conform to our contemporary predicament, in which uniformly neoliberal politicians declare Right and Left to be defunct categories and the internet dissolves all historical or cultural distinctions, producing a curious sense of paralysis. Despite being surrounded by images and information all the time, it’s hard to really see our own era. Polke throws some light on why that has come to be the case. If Polke started life escaping the crude ideology of communism, he ended it exposing how ideologies had been buried – both in post-war Germany and in the West’s claim to be post-ideological: the biggest con trick of all.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?