“At the moment, history is taught to make one group of people feel inferior and another group of people feel superior,” insisted the UK Labour Party’s equalities spokeswoman Dawn Butler in a recent fiery debate in Parliament to mark Black History Month. “This has to stop,” she added, and called for England’s school curriculum to be decolonised.

Yet it was her Conservative counterpart, the equalities minister Kemi Badenoch, that made the headlines. The minister, who was born and grew up in Nigeria, clocked up an astonishing 2.4 million views on Twitter for her attack on critical race theory, which she described as a “dangerous trend in race relations” and an “ideology that sees my blackness as victimhood and whiteness as oppression”.

That definition, of course, is widely disputed; advocates see critical race theory not as an ideology but as a methodology to understand how imperialism has led to today’s hierarchy of knowledge and value judgements. But supporters of critical race theory certainly support the calls to decolonise school and university curricula, which Badenoch went on to criticise.

“It goes without saying that the recent fad to decolonise maths, decolonise engineering, decolonise the sciences that we’ve seen across our universities – to make race the defining principle of what is studied – is not just misguided but actively opposed to the fundamental purpose of education,” Badenoch said.

Some will dispute whether the decolonisation of the curriculum – confronting and challenging the colonial mindsets that have influenced how and what is taught in higher education – is “a recent fad”; the movement emerged in American universities in the late 1980s, and the 1978 book Orientalism by the Palestinian academic Edward Said has long been invoked in calls for universities to teach outside the mainstream of Western canonical texts. But calls to decolonise the curriculum – and to confront racism in universities more widely – have certainly been ramped up in the aftermath of the death of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer in May, and the ensuing global wave of Black Lives Matter protests.

Those events shone a spotlight on racial injustice in society generally, and also on the “structural racism that continues to exist in universities”, believes Michelle Mielly, an American anthropologist based at the Grenoble School of Management in France, whose research on intercultural management focuses on diversity and identity.

Historically, universities may have regarded themselves as beyond reproach given their commitment to liberal thought, equal opportunity and anti-racism, she says. “But, all of a sudden, people who think of themselves as critical of racism in any form realised they were a part of it – because they are within an enterprise that is part of colonialism [in that] universities are where the ideas that justified slavery came from. People have been saying this for a while, but now it’s really resonating.”

A very tangible example of that occurred in June, when, after five years of campaigning, Oriel College, Oxford’s governing body voted to support the removal of a statue of the Victorian imperialist Cecil Rhodes from one of its buildings. But “to truly decolonise, what you are doing on the outside must be reflected on the inside [of a university],” says Sofia Akel, race equity lead at the Centre for Equity and Inclusion at London Metropolitan University. For Akel, decolonisation is the process of “rethinking, reframing and reconstructing the curricula and research that preserve the Europe-centred, colonial lens, challenging the institutional hierarchy and Western monopoly on knowledge”.

Some in the US have already put decolonisation at the forefront of their agenda. Duke University announced in June that it will “incorporate anti-racism” into all curricula and require every student to learn about structural racism and inequity, “with special focus on our own regional and institutional legacies”.

In the UK, King’s College London will require every undergraduate, from autumn 2021, to take a cultural competency programme, while Keele University’s Manifesto for Decolonising the Curriculum declares that for “too long, teaching in universities has encouraged a ‘traditional’ and ‘canonical’ approach that privileges the work of selected authors”.

However, such initiatives remain the exception rather than the rule. Of course, changing established structures within universities takes time, but there is also a sense that not all staff are sold on the idea of decolonisation – partly because they are unclear exactly what it means for them.

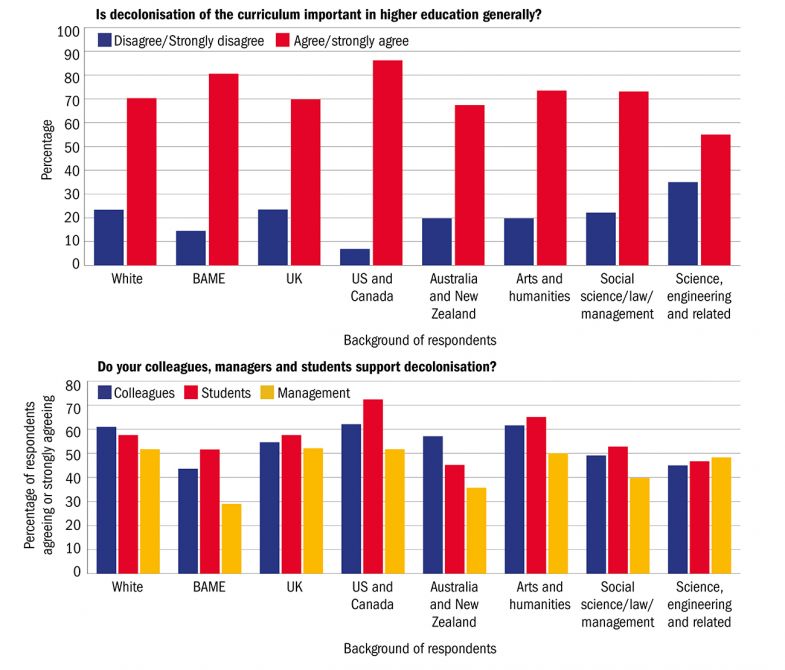

To inform this article, Times Higher Education ran a survey to explore these issues. Asked how much they agree that “decolonisation of the curriculum is important in higher education”, about half (52 per cent) of the 346 respondents strongly agree and another 19 per cent agree, against only 15 per cent who strongly disagree and 7 per cent who disagree. Significantly, 32 per cent of respondents agree that the killing of George Floyd changed their views on the importance or urgency of decolonising the curriculum.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, however, decolonisation is seen as important by a lower proportion (70 per cent) of respondents who consider themselves white, compared with those from other races (81 per cent). There are also significant regional differences, with enthusiasm for decolonisation being particularly high in North America (86 per cent).

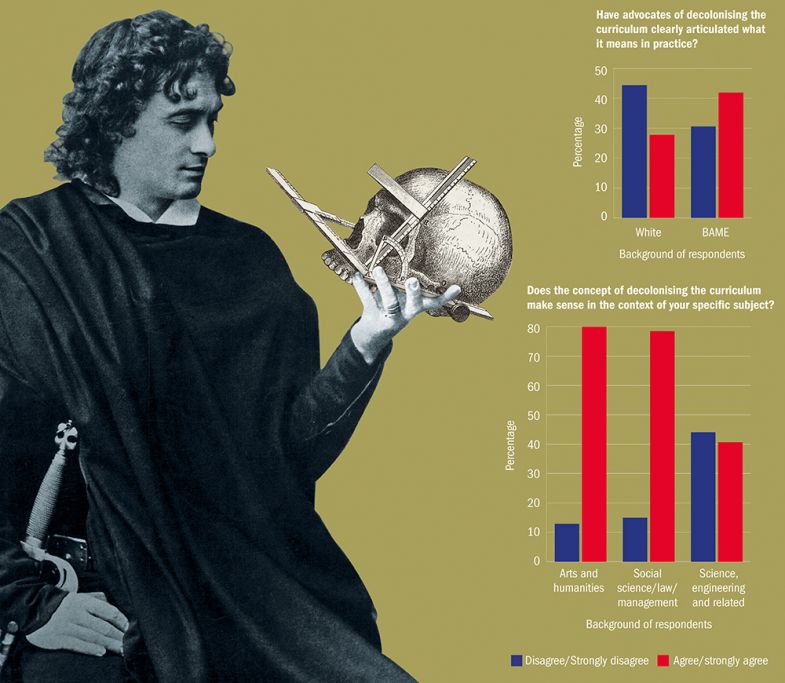

In addition, many respondents lack a clear understanding of how to act on their concerns. Asked whether advocates have clearly articulated what decolonisation means in practice, some 42 per cent disagree or strongly disagree, compared with 32 per cent who agree or strongly agree.

“I think most students, staff and even faculty would have a hard time defining what ‘decolonising the curriculum’ means,” comments one US-based humanities academic, while an Australian scholar adds: “I don’t think we yet really understand what it is or how to do it, but we know it is important.”

Some feel that seeking a one-size-fits-all definition of decolonisation is misguided. “It depends on the engagement in each single country and academic contexts – we cannot generalise,” says a UK lecturer. Others sense an element of wilful misunderstanding in the complaints of their colleagues. “There have been plenty of articles about what [decolonisation] really means and should entail,” points out one humanities academic. “It only seems to be people who aren’t actually that invested in learning about the process who don’t really seem to understand.” Another adds: “Critics do not listen carefully enough – they are unwilling to entertain change that might impact their privileges.”

In general, respondents consider their colleagues less invested in decolonisation than themselves: only 55 per cent agree that their colleagues support decolonisation at their institution; even in North America the figure only rises to 62 per cent. However, managers are seen as the greater block on change: only 48 per cent of respondents consider their managers supportive of decolonisation.

Many respondents complain that decolonisation is often conflated by managers with diversity initiatives in universities, echoing the findings of a Higher Education Policy Institute report from June, which found that this allows “tokenistic or unrelated measures to be rebranded as decolonial”. Shaun Ewan, pro vice-chancellor (Indigenous) at the University of Melbourne, admits that the decolonisation agenda “is at risk of being pulled in many ways” but insists that “diversity and decolonisation have to be linked” since they both “represent the grasping of power and privilege away from a smaller, elite group of people, into a greater diversity of knowledge systems and epistemologies”.

Jessica Welburn Paige, an assistant professor in sociology and African American studies at the University of Iowa, agrees. “In the US, the biggest barrier [to decolonisation] by far is the lack of diversity across universities,” she says. The numbers of faculty from underrepresented groups are small – and get ever smaller the higher up the professional ladder you look.

“As a result, the perspectives of the majority white population remain dominant,” she explains. “While this does not mean that there are not progressive white faculty who are working hard to decolonise the curriculum, it does mean that there are many people in positions of power that place limited value on making true institutional change.”

Some sceptics about decolonisation recoil at the idea of moving away from the canon that has been established over centuries. A decolonised curriculum would have “no Shakespeare, no Hume, or Herodotus…It would be unrecognisable,” warns one survey respondent, reflecting the recent furore at the University of Edinburgh, whose David Hume Tower has been renamed on account of the Enlightenment philosopher’s claim that black people are “naturally inferior to whites”.

Asked whether they believe that decolonisation requires some existing material to be excluded from the curriculum in order to make room for new content, 48 per cent of respondents agree, against 28 per cent who disagree. Indeed, champions of decolonisation concede that parts of the curriculum will need to be replaced, but stress that the overall focus is about adding voices, not taking them away.

“Shakespeare comes up again and again in Western education. Decolonisation is not about saying he is unimportant but reducing the amount of exposure one person receives to make room for so many other fantastic writers from around the world,” says London Met’s Akel. “For those voices that are kept, they will be [taught] in context if they need to be. Decolonisation is not trying to erase British history or white people’s history: it is broadening our perspectives. That means that we all will benefit, not just one group of people.”

So how do you decide what knowledge to include in your course when there are such vast resources to choose from?

For Melbourne’s Ewan, decolonisation should be place-based. “Conversations about what it means to incorporate Indigenous knowledge or learning into the curriculum means different things between Australia, Canada and African countries, for example, [relating to] how people there experienced colonialism,” he says. “You can’t cover everything, but that’s OK. Just let students know that you are privileging one particular paradigm of knowledge, let them know there are other knowledge systems you’re not tackling…Not recognising that your curriculum privileges one particular view assumes a certain power.”

For many universities in North America, Australia and other countries that directly experienced colonialism, establishing a department of Indigenous studies has formed a key part of their decolonisation efforts. “This is a good thing,” according to George Nicholas, professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. However, he warns that the limitations of this approach are illustrated by the development of women’s studies and gender studies as part of equality efforts in the 1980s: it risks confining redress to only one department in the university.

Nicholas adds that truth and reconciliation commissions in South Africa, Canada and Australia have argued for the development of academic programmes, across all education levels, to ensure that students are made aware of the history of the Indigenous peoples or other minority peoples in whatever area they are in. For example, Joanna Kidman, professor of Māori education at Victoria University of Wellington, explains that some New Zealand universities “sit on land confiscated from Māori in the aftermath of the New Zealand Wars and there are still enduring sensitivities about this”.

But going beyond lip service to genuinely address such sensitivities in the curriculum “has to be done with Indigenous populations and communities, [and] that’s harder” Nicholas says.

Decolonisation in practice

Decolonisation in Nicholas’ subject, archaeology, means academics’ understanding that they “do not have carte blanche” to simply turn up and study peoples and their history whenever they please. However, while it may be fairly straightforward to see what decolonising archaeology or history would mean, critics have questioned how relevant the agenda is to science subjects; “facts are facts,” as one survey respondent put it.

When asked by THE whether they agree that the concept of decolonising the curriculum makes sense in the context of their specific subjects, 80 per cent of academics in the humanities and 79 per cent of those in the social sciences agree or strongly agree. However, only 41 per cent of those in science and engineering do. And when asked whether they agree that decolonisation is as relevant to the sciences as it is to other subjects, 76 per cent of those in humanities and social science agree, compared with just 52 per cent of scientists themselves.

“Scientists never tend to see themselves as agents of colonialism or imperialism, which is what the term ‘decolonisation’ is alluding to, [but] rather as agents of progress and objectivity,” observes Daniel Akinbosede, a doctoral tutor in biochemistry at the University of Sussex. However, history shows us that this is not the case, he says.

“Colonialism and slavery could never have happened without the justification of scientists categorising humans based on the size of their skulls or saying black people were not as evolved as Caucasian people, but that connection is often lost,” he says. “Scientists may disavow these concepts now, but they were once part of science, and my fear is if we don’t get a grip on this now and start teaching students some home truths, we could find ourselves coming back around.”

For Ewan, modern academia should be more open to knowledge obtained from Indigenous communities. “We can learn a lot about the natural sciences, navigation, engineering, water flows through understanding the great navigators in the Pacific colonies and islands – why would we not use that?” he asks.

It is also important to teach the history of pedagogy in particular subjects, says ’Funmi Olonisakin, vice-principal international and professor of security, leadership and development at King’s College London – and the institution’s first black female professor. In her own subject, international peace and security, her students asked her why there were no examples of female Africans in the course, for instance.

“So I began teaching the history of the subject,” she explains. “Once you do that, students can understand the evolution of the discipline, who dominated and in what period – and that is important.”

Another concern about decolonisation relates to academic freedom.

“Any attempt to prescribe the inclusion of any text, or to exclude any lawful and evidence-based approach to an academic issue, on purely ideological – including ‘decolonisation’ – grounds would be a gross breach of scholarly freedom and the values of open academic debate,” insists Steven Greer, professor of human rights at the University of Bristol. He fears that “small, militant minorities of students and staff…will not shrink from attempting to silence lawful, evidence-based views by denouncing them as ‘racist’ or ‘right wing’ simply because they disagree with them”.

For Greer, while the West “may well have much to learn from the insights of non-Western cultures, particularly about how sustainably to integrate human society with delicate wider ecosystems, it would be a mistake to regard all cultures as equally valid in every way”.

A few respondents to THE’s survey agree. “It is a false equivalence to insist ‘Indigenous’ approaches should be taught on a par with ‘Western’ approaches without applying some form of objective evaluation as to truth and, in certain subjects such as medicine, effectiveness,” one UK academic comments.

Adam Habib, vice-chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand, also has his concerns. In South Africa, the political geographer – who will become director of SOAS, University of London in January – fears that the decolonisation debate has become “overtly political, and led by politicians, rather than being substantively academic, scholarly and pedagogical”.

“I worry that parts of the debate are too nativist, seeing identities in crude terms," he adds. “The presence of people who were previously marginalised from the academy is important, and that includes black people, but also other people of colour, poor people, the whole range of human community. There is a real danger that [politicisation] distracts from the cosmopolitan tradition of what a university is...If you are going to address local manifestations of transnational challenge, you will require both world-class technologies, coupled with local understanding. However, that does not mean we engage with this knowledge in an uncritical way…[A university] is not a political school. It is not a religious school. We are not here to enable you to feel comfortable in everything you learn.”

Simon Fraser’s Nicholas acknowledges the perils of politicisation. For him, it is important to stop and ask “who is making the decisions [about what is taught]? The majority of academics are probably very willing to ensure at least a degree of decolonisation content, but there are others who see this as simply exercising political correctness. Students and faculty have to feel safe about discussing difficult issues…Conversations [around decolonisation] can get very combative and some students may be very sensitive to the topic, particularly those from minority backgrounds. Staff have a collective responsibility to act as referees here, to ensure that students feel safe but also that everyone can share their opinion.”

Indeed, students are widely perceived to be the driving force behind the decolonisation movement, and our survey respondents agree that support for the agenda is higher among their students than among their fellow academics and managers – particularly in North America.

King’s College’s Olonisakin concurs that it is crucial for academics to listen to their students when deciding their curricula. “When I speak to students, it is about more than just the reading list – it is about not having familiar illustrations or examples that do not speak to [the students’] context or experience and that hold them back,” she says. It is important “not to create a hierarchy of identities. Everyone must feel that they are not excluded from what they learn, whether it is in health studies or history.”

She also emphasises that international students – whose languages, contexts and experiences are rarely explored – should be listened to just as closely as domestic students. And, for her, success can also be measured in student-centric terms: when the attainment gap between white and BAME students no longer exists “we know we will have been successful”, Olonisakin believes.

Importance of and support for decolonisation

But how far can the decolonisation agenda go – and how fast? In THE’s survey, respondents from BAME backgrounds consistently rate the agenda as more relevant and important than white academics do. For instance, 40 per cent of white respondents strongly agree that decolonisation is relevant to science, compared with 53 per cent of non-whites.

This isn’t surprising, according to Sussex’s Akinbosede. “It’s very difficult to convince a group of people whose lives would not be made better by [decolonisation] that they need to include it in the way they teach,” he says.

For him, progressing the decolonisation agenda “will require imagination and hard work” and he worries that “if someone can’t immediately see [the solution], they lose interest or don’t see it as possible”. He is also concerned by the universities’ unwillingness to commit significant resources to the decolonisation agenda. “Asking staff who are overworked or in precarious positions to do it is unrealistic, while ethnic minority academics, who are more likely to drive the change, may baulk at the additional burden for no professional reward,” he says.

Olonisakin says that universities should take the “carrot” approach and reward those who are able to show tangible progress towards decolonisation. However, external pressure can also be effective, she adds. “Nobody likes to be in the news for negative things, and nobody likes to come last in the league tables. Rankings should capture some of what we are talking about.”

In research, reforming the academic reward system could help too, says Nicholas. “True collaboration with Indigenous communities on research can be particularly challenging for young scholars [as] to build a career you have to have publications but collaboration in this way can take time,” he notes.

In South Africa, the depth of colonialism in higher education has led some to call for the whole system to be torn down and rebuilt around addressing 21st-century challenges, says Habib, a suggestion with which he has some sympathy: “You can’t say you want a decolonised curriculum but use the colonial architecture and parameters when rethinking it,” he reflects.

For James Blackwell, a research fellow at the Centre for Social Impact at the University of New South Wales, the key to progressing decolonisation is targets. “It should not be a controversial or impossible goal to say ‘we want x per cent of course content to be from Indigenous [backgrounds], female and/or scholars of colour’,” he says. And he gives short shrift to concerns about academic freedom and difficulty of implementation. “All these are excuses from people who are threatened by the work, too stubborn in their outlook to change, or afraid of what that change might mean for them and their understanding of their work,” he says.

“Decolonisation involves a reckoning for our disciplines and our teaching, but it shouldn’t be threatening. It should challenge us as academics and make us use our critical thinking skills,” Blackwell adds. “By giving our next generation better and more respectful understandings of these things, we are helping to reset and rewrite some of the inherent prejudices and biases present in our society.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: How should universities tackle decolonisation?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?