In the early part of the past century, many academics in red-brick universities were not particularly encouraged to do research: the core mission of the university was to teach. How times have changed.

In the UK now, some £1.5 billion is allocated to universities each year on the basis of their strength in research - and many institutions pull out all the stops to get their hands on it.

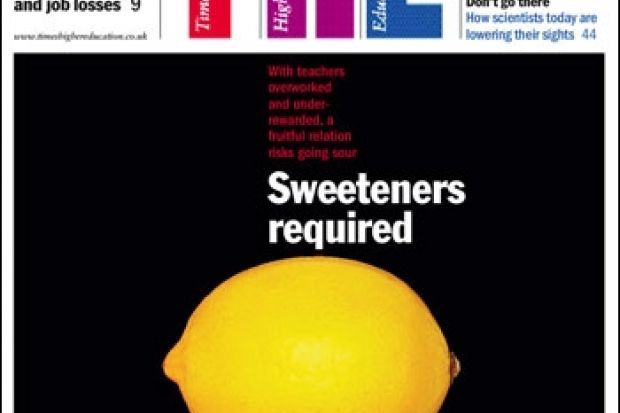

No such powerful financial incentive exists for "driving excellence" in teaching, where the vast bulk of funding follows student numbers automatically.

In the race for research cash, the familiar argument goes, teaching has fallen by the wayside, its status much lower than it once was.

"People tend to forget that the culture of research at universities is very recent," says George MacDonald Ross, senior lecturer in philosophy at the University of Leeds.

"There has been a cultural shift. People got the idea - which is not a stupid one - that it is somehow more noble to generate new knowledge than it is to pass on knowledge generated by others."

With the results of the research assessment exercise out, set to determine how quality-related research funding is distributed in this and future years, perhaps it is a good time to take stock.

This week, the Higher Education Academy (HEA) - the sector body for teaching and learning - is encouraging academia to do just that. It is publishing the findings of what is likely to be the UK's biggest study into the status of teaching in higher education. It gathers together the views of 2,768 staff who responded to an online survey.

The figures are striking, and they show that academics across the spectrum of universities value teaching equally.

Promoting people on the basis of how well they teach is seen as key to giving teaching and research equal recognition - but there is a yawning gulf between what academics believe should happen to reward good teaching and what they think actually does.

While 92 per cent think teaching should be an important factor in promotions, only 43 per cent feel it really is.

Of course academics also believe that research is important - but most think that it is fully recognised. Overall, 81 per cent think it should matter in promotion, but 84 per cent think it does.

As would be expected, given universities' differing missions, there are distinctions between institutional groups. Those from the research-intensive Russell Group and the 1994 Group of universities are more likely than those from other institutions to consider research an important factor in promotion.

But the study also indicates that some academics who work in a research-intensive culture believe that research is accorded too much prominence. In the Russell Group, 96 per cent of respondents think research is important in promotion, but a smaller proportion (88 per cent) think it should be.

When it comes to teaching, the biggest gap between aspiration and perceived reality among staff is in the Russell Group, where only 32 per cent feel teaching plays a big role in promotions, against 89 per cent who think it should. For the 1994 Group, the gap is only slightly smaller. But even in other universities, just 44 per cent of respondents think teaching truly is rewarded.

The pattern changes more radically when the position of the respondents is considered: the more junior the member of staff, the more likely they are to say that teaching is little regarded in promotion.

Only 31 per cent of lecturers think teaching is valued in promotion, but it will come as no surprise that senior managers (vice-chancellors and pro vice-chancellors) are far less likely to see a problem - 82 per cent say teaching is recognised properly.

"This may just be a tendency for those in more senior positions to say things that are more politically correct to say," Ross says.

Paul Ramsden, the chief executive of the HEA, fears that the divide between what senior managers say they do to recognise teaching and what staff perceive them to be doing could create a problem.

"It does lead to the potential difficulty that those who are in the strongest position to influence and lead are the least likely to think that major change is needed," he says.

The 2003 White Paper on the future of higher education heralded a new effort from the Government to try to redress the balance between recognition for research and teaching.

Since then, a raft of national initiatives designed to support and enhance teaching in universities has been launched. Five years on, the HEA's survey asked academics their views on the impact of these schemes.

The initiative with the highest profile was the HEA itself, which was established in 2004. Staff were next most aware of the Centres for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (Cetl), a scheme that has funded 74 teaching hubs around the country. Some 64 per cent of staff were aware of the HEA's subject centres, which were set up to support teaching in different disciplines, and 69 per cent were aware of the National Teaching Fellowship Scheme (NTFS), which honours academics for their commitment to excellent teaching. But the impact of these schemes is considered limited.

The HEA is seen as having the biggest effect on raising the esteem of teaching - 43 per cent of respondents said it had had some or considerable impact. Other initiatives thought to be significant were Cetls (cited by 40 per cent), subject centres (33 per cent) and the NTFS (35 per cent).

Although these schemes won praise, staff also remarked that national initiatives were "generally too little, too late". One national teaching fellow said he was "ignored" by his university after winning the award.

Alan Jenkins, professor emeritus of higher education at Oxford Brookes University, says: "Initiatives such as the NTFS have been a success in recognising staff with a strong record in teaching and in developing ways to judge teaching excellence. However, there is a danger that they divert attention from the central need to ensure that teaching excellence and leadership in teaching is fully recognised in institutional promotions - particularly at professorial level."

So what needs to happen? Most staff - 87 per cent - feel that there is a need to remove "obstacles to enjoying teaching".

"One obvious obstacle is that we have too many students," Ross says. The pleasure of teaching is also diminished, he says, by the edicts that some universities issue to their staff, dictating how they must teach.

He cites his own institution's decision that coursework counting towards a student's degree result must be marked anonymously.

"There is an obstacle there to fulfilling teaching because one of the most fulfilling things is to know your students as individuals and watch them develop.

"One of the things I have found most fulfilling is, over the years, developing ways of educating large numbers of students without lecturing. I am allowed to do that - but there may be institutions where you've just got to fill a lecture slot and there are limited amounts of time to do things in which students are more active participants."

Many respondents - 89 per cent - are convinced that promotions strategies designed to reward teaching are a way to raise its esteem.

Some recent research suggests that promotions are changing. In a study last year, Jonathan Parker, a lecturer in American politics at Keele University, found that there had been some movement in promotions procedures - although senior academic positions were still reserved for more research-active staff.

In the HEA study, qualitative interviews with 31 staff revealed "a general feeling that there had been a gradual improvement in promotion prospects for academics who chose to focus on teaching ... but that these changes were overdue and continued to be slow in materialising".

When the framework agreement on the modernisation of pay structures in higher education was reached in 2004, some universities took the opportunity to expand the role of teaching in promotions procedures.

Imogen Taylor, a professor of social care and social work at the University of Sussex, says: "I think that is very positive. My view is that teaching is much more recognised than it was even five years ago, but there is still a glass ceiling on promotion - it is very hard to get to professorial level and be excellent in teaching without also having an excellent record in research."

The University of Bristol is one research-intensive university that has altered its procedures.

Dudley Shallcross, professor of atmospheric chemistry at Bristol, says: "There has been a real turnaround. Bristol introduced a 'pathway three' for teaching in 2006, and I am one of the examples of that."

Shallcross won promotion to reader on the basis of his research, but he also had to make a strong case that he was contributing in new ways to the teaching in his department.

Since then, he has been promoted to a professorial teaching fellowship, primarily on the basis of his teaching.

"If you are a good teacher, you attract good students to do projects with you - and that leads to good PhD students - so there are also very strong drivers even from a research angle to be good at teaching. That is something that was emphasised to me from Day 1 here," Shallcross says. "At Bristol, you cannot progress if you are weak in teaching."

Valerie Wass, professor of community-based medical education, says there is still some way to go at her institution, the University of Manchester.

"We have made progress here - they came up with a teaching-fellow track and a lecturer track - but it has been undone at the senate.

"We are also going to have our curriculum reviewed, but the dean has appointed a committee that is totally unconnected with medical education - it is all the big research names. It shows where they think the power is.

"Similarly, when they've appointed the vice-president for teaching and learning and the associate dean for teaching and learning, they've appointed researchers who haven't got a background in education. It is very disappointing when you work hard to get a masters and a PhD in education. Those who have got the background in teaching don't get those high posts."

At the University of Leeds, those who apply for promotion to a professorship have two routes - one through research, the other via teaching.

"If you apply on the research route, you merely have to give evidence of international excellence in research - you don't have to say anything whatsoever about teaching or administration," Ross says.

"If you apply through the teaching route, you have to give evidence that you have at least national excellence in research as well as international excellence in teaching."

Even where there is parity in promotions procedures, the HEA's study suggests that this alone is not enough to ensure that teaching gains the same esteem as research.

The academy's interviews with staff suggest that teaching career paths in universities do not have the same status as posts that are research-orientated.

One of the survey's respondents said: "We now have a career structure on our website for 'university teachers', but it is seen as a second-class thing. One of the things that can happen is that if someone is not as research active as a lecturer or senior lecturer, they'll get moved sideways to university teacher."

The report says the perception remains that teaching careers "are for those who cannot quite make the grade as research-active lecturers".

A very high proportion - 92 per cent - of survey respondents said the culture in universities needed to change to recognise teaching, and 200 submitted comments emphasising the importance of leadership and management in achieving this.

"I would like to see senior management act as if teaching/learning is important rather than just talk about it as such," one said.

According to another: "Much depends on leadership from the top down, reinforcing the message that research and teaching are of equal value."

The HEA's interviews with academics also highlight the difficulties involved in assessing good teaching.

"Interviewees felt that a major obstacle to the reward and recognition of teaching in higher education was the lack of any clear and universal method for assessing teaching excellence," the report says.

"Research output, it was generally agreed, could be measured in a relatively straightforward manner. Interviewees thought that assessing teaching quality was more problematic."

Taylor from Sussex, who has experience of sitting on promotions committees and was on the RAE panel for social policy and social work, accepts that it is tough to measure teaching excellence, but she says the sector should still strive to do it.

"We are very experienced at peer reviewing research - we are not very experienced at peer reviewing teaching.

"It is much more difficult for promotions committees to evaluate teaching than research. It can include a whole range of materials and can be quite lengthy - different material from stakeholders, student evaluations, peer observation from colleagues.

"My experience of looking at evidence in promotions processes is that for teaching one is looking at a fairly bulky package of material, and we still haven't sorted out how to convey this material in a succinct way. We don't have a set of agreed criteria - in the last RAE we were using three broad criteria: originality, significance and rigour. In teaching, we don't have that agreed focus.

"We need sufficient pedagogic research to know what we mean by good teaching - but I believe we are getting better at thinking about what constitutes the evidence for it."

Oxford Brookes' Jenkins agrees. "I would say that there are three different aspects to this. One is 'classroom' teaching, another is pedagogic research and another is shaping teaching institutional or national policies and practices. I think strength in the second two is what is particularly needed for promotion to professorial level," he says.

Another method of evaluation is peer observation, which is advocated by Tim Birkhead, professor of behavioural ecology at the University of Sheffield (see box, page 32).

Ross, however, is not a fan of peer observation. "It encourages the idea that teaching consists of a public performance; whereas, in fact, most of what goes on in good teaching is behind the scenes - it is to do with how you structure your materials, how you interact with students, assess their work and encourage them.

"There has been far too much emphasis on a good teacher being somebody who can give a fluent, entertaining and amusing lecture, and I personally think that if there is anything worse than a bad lecture it is a good one - it sends students away with a warm feeling, thinking they have got all they need in order to pass their exams.

"If they realise they are not learning very much from the lectures, then they will read the books and talk to each other rather than relying on what they have received passively. I don't advocate bad lecturing, but rather teaching in ways that involve much more activity and input on the part of the student."

Student involvement, however, should not stretch to using "satisfaction" as a measure of teaching quality, Ross says.

"From what I've seen, really good teachers tend to get quite average ratings from students - their ratings tend to be polarised. Lazy students who just want to be told what they need to know (to pass exams) give good teachers low ratings because they are expecting them to work, but other students love it because their other classes aren't challenging enough."

He favours a focus on teaching portfolios. "If everybody kept a reflective portfolio on how they teach, what they do and why, that would give reasonably objective evidence of their practices that could be looked at by somebody else without putting performance on the stage."

Ramsden argues that teaching can be assessed fairly. He hopes to demonstrate this in the second part of the HEA's study (due out later this year), which examines institutional policies for recognising teaching and how these policies are being implemented.

"There are examples of very good practice in developing criteria and methods for assessing teaching performance in higher education, and I think one of the tasks we have before us is to disseminate those methods more widely in the sector.

"For example, our senior fellows have to demonstrate that what they have done in teaching has had an impact outside their own institution, nationally or internationally, and that that impact can be measured objectively and is comparable with the measurements of research," Ramsden says. "It's important to not think that you have to have criteria totally different in character for measuring teaching and research - you are looking for a convergence between them if possible."

In a submission to John Denham, the Universities Secretary, on the Government's review of higher education, Ramsden recommends that institutions be given funding to develop "more robust" criteria for appointments and promotions related to teaching and to introduce training for staff involved in making promotions decisions.

"The Quality Assurance Agency should systematically review progress and monitor staff perceptions of the effects of these changes. The Leadership Foundation for Higher Education should address the perception among many academic staff that the leadership of some deans and heads is frequently inimical to good teaching," Ramsden's report says.

As Taylor argues, the longer it takes for this to happen, the more staff - and therefore students - will miss out.

See: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/ourwork/research/rewardandrecog

'Two experienced teachers can tell quickly whether someone is effective during a lecture'

Teaching is often undervalued and inadequately rewarded - mainly because it is so difficult to assess.

Part of the problem is that teaching is very diverse: it ranges from activities undertaken outside the lecture theatre, such as management and curriculum development, through to those at the point of delivery: lectures, field course instruction and small-group tutorials.

In terms of assessment, the response to these diverse activities has been a proliferation of rules, regulations and guidelines. Despite their baroque complexity, they provide only diffuse indicators of teaching performance and tend to stifle originality. We need diversity, not uniformity, in university teaching.

When it comes to assessing someone's ability to deliver teaching, I would sweep away all this complexity and replace it with something simpler. This approach may not satisfy the bureaucrats, but it is cheaper and, I believe, more effective. Simplicity may be the key. Good teaching is like fine wine: difficult to define, but you know it when you get it - especially if you have had some prior experience.

My strategy to assess teaching would be unannounced peer observation (unannounced to preclude any special preparation, whose farcical nature is epitomised by Ofsted inspections of schools). Two experienced and highly regarded teachers can tell relatively quickly whether someone is effective in terms of the structure, content, methods, delivery and ability to inspire students during a lecture or a tutorial.

I can hear the squeals of protest already. Of course, peer observation is not without problems. I well remember my nervousness on being told early on in my career that a couple of colleagues would be attending some of my undergraduate lectures to see how I performed.

Well, having survived this, I can say that it isn't that bad. Colleagues are far less threatening than a room full of undergraduates. Unless one really is useless as a teacher, there is no reason why anyone should feel insecure about this when we have few qualms about giving research seminars in our own or other departments.

Two people sitting at the back of someone's lecture and independently scoring their effectiveness (say, with a score out of ten) across a range of criteria is the most direct and cost-efficient way of assessing how good a teacher is. Their respective scores can be used to check on consistency. The reluctance to do this is, I think, a fear that it is somehow too invasive. But in our busy academic life, a pragmatic solution to this otherwise tricky issue will benefit everyone.

Tim Birkhead is professor of behavioural ecology, University of Sheffield.

GENIUS VALUES TEACHING, SO SHOULD THE REST OF US

A while ago, I opened two centres of excellence in teaching and learning (Cetls) in a research-intensive university. My speech was an encomium to the value and centrality of teaching in universities. That, and my genuine enthusiasm for a research-intensive university opening two Cetls, had, I thought, gone down well.

I was, then, surprised to receive a letter from a professor who had heard me speak castigating me for suggesting that universities were places for teaching. Teaching, I was told, is "what schoolteachers do".

I was guilty of either precipitating or perpetuating "a perceptual shift" that suggested that universities had "an obligation to teach". They apparently do not; they are rather places that should "provide opportunities for learning". The teacher, and by implication the vocation of teaching, had no place in the university.

I pride myself on replying to the letters I receive. I have not, however, replied to this one. The academy has its origins in teaching and in contesting what is known, how it is known, and how knowledge can and should be conveyed.

There were epistemological differences between Plato and Aristotle, between the Academy and the Lyceum: but there were pedagogic differences, too. Moreover, these were teachers who had followers, with pupils who profoundly defined themselves by what they were taught and by whom they were taught.

That experience has characterised the academy for more than two millennia. Lives transformed by university teachers, some great, some humble; some intellectual leaders, some accomplished synthesisers. Students anxious to take a particular person's course; graduates aspire to "study with" - not to have their higher learning in some desiccated way "facilitated by" - a supervisor of repute and standing.

I remember our eldest daughter encountering a truly charismatic university teacher for the first time. "He's so good, Dad, that I get there early and sit in the front row" (he was good looking too!). Suddenly, in the way fine teachers do, new intellectual horizons were opened, the challenge to commit more and to take greater responsibility for learning was implicit in the way he taught and, of course, it elicited a response. Remove this kind of teaching, decentre or devalue it, and you remove a pulsing heart from the life of the university.

Reflecting on what has happened in universities this century, the story is, at least in part, a story of the rediscovery of teaching. Some of it, to be sure, was driven by the advent of fees and an apprehension that students would become more discriminating (I was never sure why anyone feared this: students should be discriminating). Some of it was cast in a mechanistic language that suffused debates on "learning and teaching". I thought, symbolically and actually, we lost much in the subtle inversion of "teaching and learning" as it transposed into "learning and teaching".

Slowly, though, we are revaluing teaching. Teaching and university teachers are better valued: by teaching awards, in promotion and reward procedures, through the work of the Higher Education Academy, and through an acceptance of the legitimacy of student evaluation, partly through the National Student Survey, partly through more locally sensitive processes at institutional, departmental and course level.

Some years ago, as a head of department, I met fierce resistance from some colleagues when I introduced peer observation of teaching. It was as if they thought university teaching was a private act, conducted behind closed doors, by only partially consenting adults. Now such accountability and reflective practice is nearly the norm.

There is still some way to go. Teaching, like all arts, is partly craft, partly professional commitment and partly inspiration. Sometimes, as teachers, we are not on form, some days we are a bit flat, but we are still efficient and competent, and students value that. Some days we can express familiar ideas and traditional concepts with a freshness that excites both students and teacher: as if the familiar was freshly discovered or newly urgent.

We do need to think through issues of contact hours, not just how many, but what kind. We also need to be clearer in what we expect of students, how they move from directed to independent study; how they make best and most rigorous use of the unprecedented intellectual and academic resources available to them. There is a balance between fine teaching and committed student learning: we need to find and articulate that.

But all this is so much better, so much more authentic, so much more exciting, if we have universities animated by teaching and receiving its proper recognition, within the academy.

Recently, in Washington, I realised why I thought my professorial correspondent so profoundly mistaken.

I was buying CDs and I picked up several recordings by the remarkable violinist Hilary Hahn. At 16, she recorded Bach's D minor partita, in a stupendously powerful reading.

She did not, however, draw attention to her genius, but rather dedicated the recording to "her teacher", the great Jascha Brodsky. Brodsky died soon after the recording. Hahn, though now launched on an acclaimed international career, moved to study with another teacher, Jamie Laredo.

I then recalled that, in the last year of his life, Franz Schubert, while exploring remarkable new frontiers in the String Quintet and the last piano sonatas, was taking lessons from Simon Sechter, Vienna's most rigorous teacher of harmony and composition.

Genius values teachers; so should the rest of us.

David Eastwood is chief executive, Higher Education Funding Council for England, and vice-chancellor elect, University of Birmingham.

FROM THE FRONT LINE: HOW TEACHERS VIEW THEIR TREATMENT

A selection of comments from academics who were interviewed for the HEA report or who responded to the online survey.

"My major concern relates to senior managers paying lip service to the value of teaching. Management culture says research is all; teaching is for those who can't do anything else."

"Stop (really stop) promotions based on research outputs alone."

"In 2001 I'd been a teaching fellow (at this institution) for four years. The v-c visited the campus that I was working on, and I asked him in a public forum what the university would do to support people like me. He was rather embarrassed by my question and said that I could leave it with him and that he would give me an answer within two weeks. I never heard anything else from him."

"Try to get old universities to not see 'teaching' as a dirty word that gets in the way of research."

"It's very interesting because the more teaching awards I get, the less teaching I seem to do!"

"Quite a lot of people have been appointed to the position of university teacher. But some people have been moved into that category. If people feel that they are no longer able to maintain a research profile, then they can move to this career path with promotion prospects exactly the same as they are for lecturers."

"In principle you can achieve promotion on the basis of teaching, but it rarely happens. I think we need to implement the policy (of promoting people for teaching excellence) with an eye on numbers of promotions that are actually made this way."

"It (teaching) is almost a necessary evil. This is what I find hard to comprehend. We make money from teaching - that's why we keep taking on more students. But what they (the academic department) really want you to do is get research bids."

"Few people believe that they can build a career on teaching and learning and (people) think that it's quite dangerous to attempt to do so."

"How do you judge the quality of someone's teaching just on the basis of an application form? You can't, is the answer. I don't think that higher education or the Higher Education Academy are going to crack this problem (of assuring adequate reward and recognition for teaching) unless there are systematic peer observations for teachers."

Editor’s note

We are happy to point out that the HEA report referred to in this article was part of a joint collaboration with the “GENIE” Centre of Excellence in Teaching and Learning at the University of Leicester.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login