More than three-quarters of university staff feel academic freedom of speech is more restricted in their country than it was 10 years ago, a major survey has found.

Seventy-seven per cent of respondents to Times Higher Education’s academic freedom survey agreed that free speech on campus had diminished over the past decade, while just 12 per cent disagreed and a further 11 per cent expressed no view either way.

This sense that free speech on campus has been chilled is particularly strong in the US, where 83 per cent of respondents felt this was the case, and in psychology (80 per cent) and clinical health (89 per cent), where sex and gender issues loom large.

One UK psychology academic explained that it was increasingly difficult to argue with any “strongly held position by activists” on topics around “gender, colonialism, Israel/Palestine, neurodiversity” because “any diversion from the accepted line is seen as meaning you are a bad person rather than just someone who disagrees”.

“Student consumers now increasingly dictate what they want to hear in lectures and seminars,” said another academic on students’ “disproportionate power” in the classroom.

One UK legal academic in his thirties admitted that he taught “with as little personality as possible because significant numbers of students find offence in anything that they dislike”.

However, other academics are seen as a greater check on academic freedom than students, with an average of 3.15 on a five-point scale (where 1 was “strongly disagree” and 5 was “strongly agree”) against 2.85.

At one UK university, a scientist complained that humanities academics were “targeting the scientists who are actually doing the work to combat climate change” by demanding that his institution “stop all work with ‘fossil fuel’ companies”, adding: “There is real fear and intimidation.”

University managers are bottom of the list of checks on academic freedom (2.27), although this was higher in Australia (2.44).

Other respondents highlighted the rise of bureaucracy around campus speakers. “Ten years ago I did not need permission to invite guest speakers/lecturers for example,” said a UK law professor, who added: “Now, I have to complete a whole external speaker form, await a risk assessment from an unknown source, and receive permission before I am even allowed to invite an external speaker.”

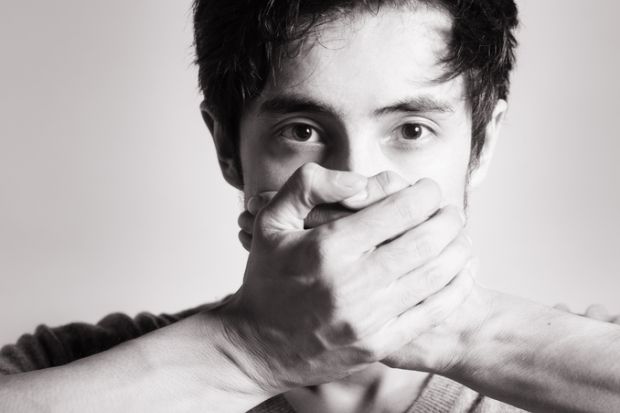

The largest restriction of speech was, however, self-censorship, which was practised by 68 per cent of respondents, rising to 74 per cent of women and 80 per cent of those based in the US.

“I do self-censor in terms of what I say in the public domain because I fear it may harm future job applications,” admitted a male UK arts and humanities postdoc.

Nonetheless, academics felt it was also important to avoid offence in the classroom, although there were significant splits by age range: 63 per cent of under-40s believed it was important to avoid offence or harm in the classroom, compared with 39 per cent of those in their forties and 42 per cent of over-60s.

Yet some academics believed avoiding offence was an impossible task with some students, with one UK-based clinical health professor stating that “there will always be students, academics or just parts of society that have an entrenched view which differs from yours and therefore they will be offended”.

The survey, completed by 452 respondents in 28 countries, also addresses issues including social media use, the acceptability of management interventions in curricula, boycotts, and the right to criticise one’s institution.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?