Before tuition fees in England were raised to £9,000 in 2012, there were arguably clear lines of distinction between different types of higher education institution.

At one end of the spectrum were very selective universities with poor records on access, while at the other were “recruiting” institutions with lower entry standards but a broader profile of students from different social backgrounds.

Half a decade on, are these lines starting to become more blurred? The latest set of admissions data showing the profile of students entering university in 2017 suggests that this may increasingly be the case.

The strongest evidence in the Ucas End of Cycle Report 2017 for this trend comes from data showing a convergence between universities according to the school-leaver grades that they accept.

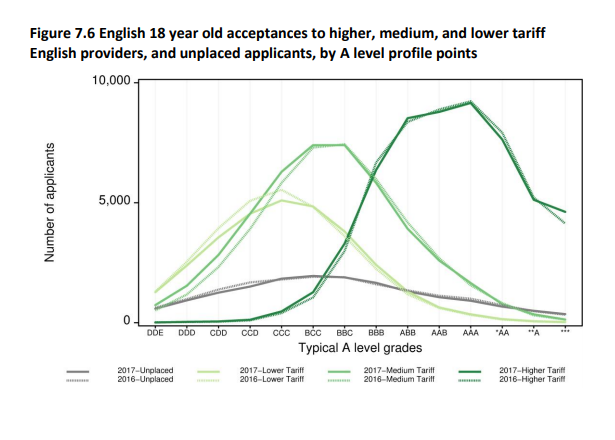

This pattern is particularly clear when looking at the two groups of institution that over the past few years have accepted students with grades below the highest level (lower- and medium-tariff universities).

Among these two groups the average attainment of the 18-year-olds starting courses – measured by the number of A-level equivalent “points” achieved – has been merging.

For instance, between the grades of DDD and CCC, medium-tariff universities recruited 1,970 more students in 2017 – about half the overall increase in acceptances of 18-year-old A-level students to such universities – while lower-tariff providers had a fall of 1,530 acceptances at these grades.

It suggests that the UK government’s policy of allowing unlimited recruitment of undergraduates – alongside the growing importance of fees to universities’ income – is leading the bulk of institutions to the same place: a grab for the wide pool of students who miss out on the top grades.

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, said that many of the predictions before the reforms happened were that there would be a “squeezed middle” of universities that struggled to find a place in the new landscape.

He said that it was therefore “interesting that the effect of liberating the market has not been the same as was predicted”, although he added that the UK still had “one of the most hierarchical higher education systems in the world, so although this change has happened, it has only been to a degree”.

Mr Hillman, who was special adviser to Lord Willetts when he was the higher education minister delivering the funding reforms, said that more differentiation between universities could also happen again very quickly, especially if problems with the “broken” bit of the system – funding for part-time students – were fixed.

This could lead to universities that “used to serve” such students having the financial incentives to re-engage with “the local, civic, part-time [provision] role” that they had played, he said.

Meanwhile, there is also evidence that universities with different admissions profiles are also becoming more alike in terms of access for disadvantaged students, albeit very slowly.

Although the most disadvantaged students are still 10 times less likely to go to a higher-tariff institution than their advantaged counterparts, this ratio has been moving in the direction of the figures seen at medium- and lower-tariff universities.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?