Debate on cloning is confusing the issue of using embryonic stem cells, says Peter Andrews.

Some 3,000 years ago, a scribe in the Chaldean city of Nineveh wrote on a clay tablet: "When a woman gives birth to an infant that has three feet, two in their normal positions attached to the body and a third between them, there will be great prosperity in the land."

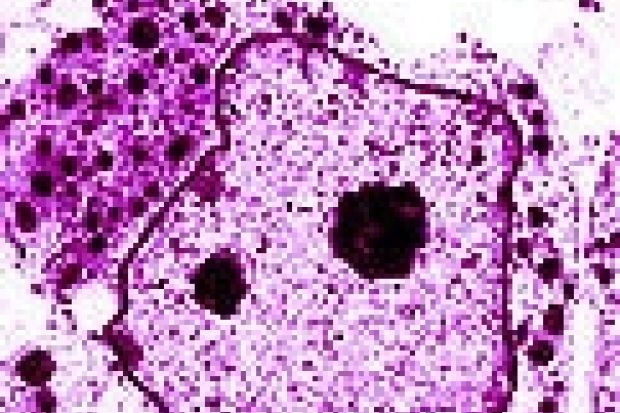

This is almost certainly the first description of a peculiar type of tumour called a teratoma, a haphazard mixture of tissues, such as bone, nerve and muscle. Highly malignant forms occur more commonly as testicular cancers. Study of these cancers has enabled us to grow embryonic stem (ES) cells as well as offering the prospect of their use as sources of tissue for transplantation therapy.

The malignancy of testicular teratomas is mainly due to the presence of a type of stem cell known as an embryonal carcinoma (EC) cell. During the 1970s, lines of EC cells from mouse teratomas were established in culture. It was shown that EC cells closely resemble ES cells, the forebears of all the different cell types that make up the developing embryo.

The way in which both have the potential to turn into more specialised cell types - a process known as differentiation - was of particular interest. Indeed, it was through parallel studies of teratomas and embryos that scientists were eventually able to successfully isolate ES cell lines directly from early mouse embryos.

While many of the processes that control embryonic development are shared by mice and men, despite millions of years of separate evolution, some must be unique to humans: clearly we are not just large mice without tails. To get a better understanding of how human embryos develop and how the process can sometimes go awry, we must study the embryonic cell differentiation directly.

Some 20 years ago, we began to work with EC cells from human testicular teratomas, first at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia and then at Sheffield University. One line that we studied, called NTERA2, is particularly prone to differentiate into nerve cells. Scientists at the University of Pittsburgh are investigating whether transplanting neurones derived from EC cells can help stroke patients.

However, EC cells are cancer cells and concerns can be raised as to whether their derivatives will be truly "normal". Hence the recent excitement surrounding the successful derivation of human ES cell lines from "excess" embryos that would otherwise have been destroyed following IVF treatment for infertile couples. These are clearly different from mouse ES cells, underlining the importance of being able to use human ES cells to investigate human development and gain clues to the causes of infertility and birth defects.

When the Human Fertilisation and Embryo Act was passed in 1990 - providing the legal authority for research using human embryos - it was envisaged that such work would focus on understanding the problems of infertility as well as the causes of abnormal embryonic development. However, it has occurred to many people that the various cells produced in culture by the differentiation of ES cells could be transplanted into patients, to treat a wide range of diseases. For such use, the 1990 act required amending.

This relatively small change was confused by the parallel development of "cloning" technology. It was shown that the nucleus of an "adult" cell could be used to replace the nucleus of a fertilised egg, supporting the development of an embryo genetically identical to the donor. This approach would allow the derivation of ES cells and, eventually, differentiated tissues that were genetically identical to a prospective transplant recipient.

This could circumvent transplant therapy's long-standing problem of immune rejection. Such a "cloning" strategy would require further modification of the 1990 act to create an embryo specifically for this purpose. Unfortunately, the recent public debate has confused these two separate issues, tending to dwell on the emotive "cloning".

There can be no doubt that the study of human ES cells will provide invaluable insight into the process of human embryonic development. A host of benefits, beyond the causes of infertility and the origins of birth defects, will doubtless flow from this. Many of the diseases that afflict adults, including cancer, arise from defects in the mechanisms that also guide embryonic development. Understanding how they operate normally in the embryo will certainly shed light on how they may operate abnormally in diseases.

In Sheffield, our own research focuses on how ES cell differentiation is regulated, using cell lines derived by James Thomson in the United States. But it will be important to derive our own lines too. It would be unwise to base all our conclusions or just one or two.

ES cells may also provide a wide variety of tissues for the transplant surgeon. Much has recently been heard about "adult" stem cells and what they might achieve, implying that use of ES cells could be avoided. But we still have very little understanding of these and it is far from clear whether they will be as useful as some recent reports have suggested. It is likely that ES cells and adult stem cells will provide complementary tools; it is far too early to decide on their respective benefits.

"Cloning" technology adds very little at this stage. Ultimately, we may find this approach useful to match ES cells to their potential donor. However, there is still much to be done to assess what ES cells can do first.

Peter Andrews is the Arthur Jackson professor of biomedical science at Sheffield University and the first scientist in the United Kingdom to work on human stem cell lines in culture.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login