The new play Admissions opens by establishing the pro-diversity bona fides of Sherri Rosen-Mason, the admissions director at Hillcrest, “a second tier, on-the-cusp-of-being-a-first-tier” prep school in New Hampshire. Sherri has summoned her colleague Roberta to scold her about the admissions brochure she has produced. As Sherri explains, she has recruited more non-white students to the school than was the case in the past, increasing its non-white enrolment from 6 per cent to 18 per cent, still “embarrassingly low”, but progress.

What has Sherri upset is that she’s just seen the draft admission brochure, and only three of the 52 people with photos are not white. Sherri calls this an “absolute failure” and says that she can’t recruit more minority students if prospective students look at a brochure and see only white faces.

Roberta notes that Sherri isn’t counting one student, Perry, pictured with some other members of the basketball team, including Sherri’s son. “Perry's black! His father's black!” shouts Roberta, to which Sherri responds that Perry’s father is biracial (and his mother is white). Roberta notes that Sherri counts Perry as black when she boasts about 18 per cent minority enrolment.

Perry is black, Sherri acknowledges, but he looks “whiter” than her own (white) son. Perry “doesn’t read black in this photo, that's the issue”, Sherri says. His photo won’t encourage another black student to enrol.

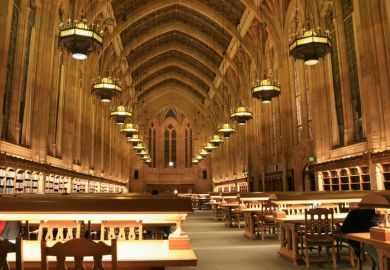

The play – which opened last week to strong reviews at the Lincoln Center in New York – then describes how Perry and Charlie, the son of Sherri and Bill (the headmaster), are applying to university. Perry’s mother tried to convince him to apply to Middlebury College, where her sister-in-law was a dean. But both boys had their hearts set on Yale University.

When early admissions decisions come out, Yale admits Perry and defers Charlie. And Charlie thinks he knows exactly why.

He tells his parents that he knows more about Perry, his long-time friend, than they do. Charlie knows that his grades are better than Perry’s, that he is taking three advanced placement courses and Perry only two. Admissions officers clearly preferred Perry over Charlie because of his race, Charlie says.

The two boys went on college tours together. When Perry’s white mother accompanied them, nothing special happened. But when his biracial father was along, the picture was different.

“All those admissions officers who all had that same vague phoney bullshit persona suddenly, like, came alive,” Charlie says. “They looked at him more, made more eye contact, were just a little more interested in every word that came out of his mouth, laughed harder than they needed to at every dumb thing he said, feeling so proud of themselves, so smug, they’re changing the world on the daily and it was like, I AM STANDING RIGHT. HERE. I AM A HUMAN BEING JUST LIKE HIM AND I AM STANDING RIGHT HERE.”

While the play is in part about Perry and his father – and other non-white people who are mentioned – all the characters who appear onstage are white. And all (with the exception of Charlie) identify as liberals. Charlie, whose middle name is Luther – for Martin Luther King, not the theologian Martin Luther – stuns his parents when his deferral from Yale sets off tirade after tirade.

Of Perry’s mother, he says that she acts as if “it’s this huge achievement that a not totally white baby popped out of her vagina”.

He describes a discussion in English class where students are reading Willa Cather, whom Charlie notes wasn’t only a woman but was “like, basically a lesbian”. A fellow student complains that reading books by white people is “soul crushing”, and Charlie recounts telling her that they “rarely” read books by white people – “thanks to my parents actually” – but also says, “You’re white, Joanna. So what are you talking about?”

Admissions leaders in real life would be quick to point out that getting into Yale isn’t about a formula, and that most (real) black people who may receive help in the admissions process lack the money and connections of fictional Perry. Some elements of the play may ring true, including observations about the hierarchy of prestige believed by many white liberal educators. Sherri attempts to console her son by saying, “Oh, honey, if you’d applied to Cornell, you would have gotten in, that’s a no-brainer.”

In many ways the target of the play is not admissions alone, but the attitudes of white, liberal educators who support diversity in admissions but may not be willing to sacrifice their own status.

The play’s author, Joshua Harmon, is not known for pulling his punches.

He wrote Ivanka, imagining the president’s daughter as the lead in a play modelled on the Greek classic Medea.

And he wrote Bad Jews, about cousins gathered to mourn the death of their grandfather – and to bicker. Audience members laughed and winced (sometimes at the same time) about his portrayal of modern American Jewish and not-so-Jewish life.

Audience members may be having a similar reaction to Admissions. The New York Times described attendees “roaring and clapping and then seeming to want to retract both responses as Charlie veered into ever more uncomfortable ideas”.

In an interview on Lincoln Center’s blog, Mr Harmon said that the play is about using admissions to make points about white people – and especially certain kinds of white people.

The play is “not really about applying to college”, Mr Harmon said. “That’s the container, I suppose, to be able to ask the larger questions with which the play is trying to engage. At its core, this play is an examination of whiteness: white privilege, white power, white anxiety, white guilt, all of it. Conversations on matters of race are happening with greater frequency and intensity all over the nation, which is so necessary, and there are so many ways to have them, and so many different aspects and views to consider and digest. This play is trying to hold up a mirror to white liberalism, while remaining very conscious of the fact that this is just one narrow slice of a much larger conversation.”

This is an edited version of a story which first appeared on Inside Higher Ed.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login