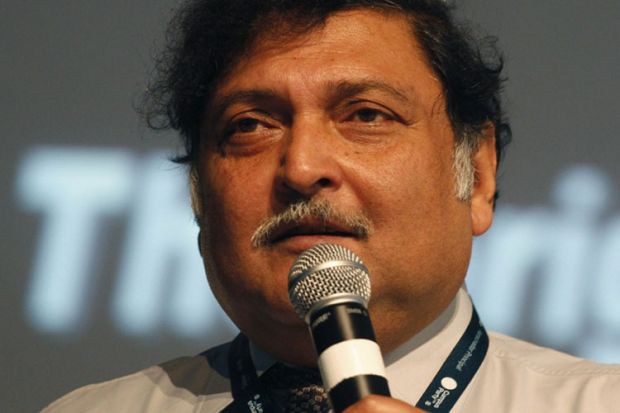

Source: Campus Party Brasil

When Sugata Mitra won the TED Prize, it didn’t just give him $1 million (£660,000) to put ideas about internet-based learning into action.

It also gave the professor of educational technology at Newcastle University a global platform for his theories, which have now been adopted in thousands of schools and communities worldwide.

It is an impressive illustration of what winning the prize, awarded by the California-based not-for-profit ideas network TED, can do for a scholar’s global impact.

The money allowed Professor Mitra to build seven “self-organised learning environments”, classrooms of the future where children study by trying to answer big questions for themselves, in groups, using the internet.

Two of the labs are in the UK, in North Tyneside and County Durham, and five are in India. The project’s flagship centre, Area Zero, which opened near Kolkata earlier this month, can accommodate up to 48 children at once, using 15 computers.

Using the internet to learn, Professor Mitra said, better reflects the way young people now use mobile phones and tablets not only to entertain themselves and interact, but also to access information.

The TED money also supported the creation of an interdisciplinary centre at Newcastle to study self-organised learning, and the development of a “granny cloud”, a community mainly comprising retired teachers, who encourage learners via Skype with questions and assignments.

Drawing on technological support from Microsoft and Skype, the learning labs form a digital platform that Professor Mitra calls the School in the Cloud, allowing anyone anywhere in the world to participate in the experiment.

And they have joined in droves. More than 10,000 self-organised learning environments (SOLEs) have been set up across five continents, and a SOLE toolkit has been downloaded more than 67,000 times.

Professor Mitra said that after he won the TED Prize, self-organised learning environments seemingly went “viral”.

“I wouldn’t have imagined that TED would be so instrumental in spreading this so very quickly,” he said. “It was a life-changing thing because until TED I was struggling around, tinkering with a few places here and there.”

The project has opened up new research avenues for Professor Mitra, who wants to explore why children can apparently learn more quickly – and pick up new languages more swiftly – when working independently in groups.

Two years on from his win, he hopes his idea of using the internet to deliver more effective and democratic education can continue to transform curricula and pedagogy.

Not only does Professor Mitra want more schools to adopt his approach, he hopes that children will be able to use technology in their exams, too.

“Children are alienated from school because school prepares them to store answers in their head, from an age when you had no other way to fish for an answer,” Professor Mitra said.

“That’s all gone now, so naturally children don’t understand. A question asked today all over the world is ‘why is it important for me to learn this’ and we don’t give them an answer very often.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login