With nearly every university set to introduce some form of top-up fees from 2006, THES reporters take a look at who is planning to charge what and why

The competition created by the white paper proposals to introduce fees of up to £3,000 a year will not be between institutions, as envisaged by ministers, but between courses and subjects, according to a survey by The THES .

Nearly all universities plan to charge the full £3,000 annual tuition fee from 2006, if the necessary legislation is passed. But a handful of institutions said they would not be charging full fees for all courses and subjects.

The findings indicate that at some universities variations in tuition fees will depend on the cost of providing a course. Classroom-based subjects will be cheaper than laboratory-based subjects.

Peter Cotgreave, director of pressure group Save British Science, said: "This would be a disaster for science. It is already bad enough, but for people to want to charge more for science would be a retrograde step.

"At a national level, we have to think about what we need in the future. I don't understand how the prime minister can stand up and talk about the importance of science and the knowledge economy and all the money that the government is putting into science - and then ask universities to be more business-like and therefore close their chemistry departments. "The reason is not only to do with student demand but funding mechanisms.

The funding we get for chemistry is insufficient and then to bring in a system of top-up fees that makes science more expensive seems barking mad."

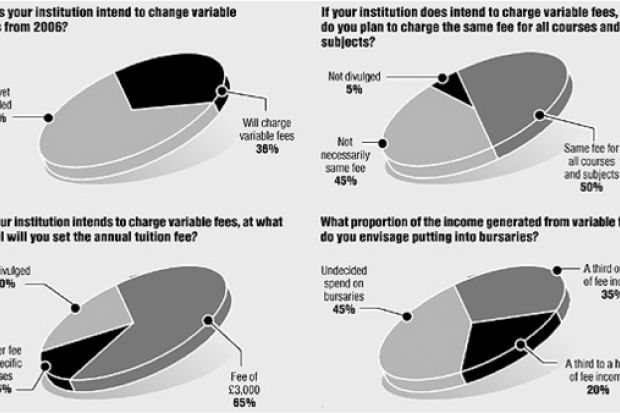

Some 55 universities and colleges representing all types of provision responded to the survey. More than a third answered direct questions on the level of fees they proposed to charge. The remainder mostly made general statements on their current thinking.

All 20 of the detailed responses cited plans to charge variable fees.

Respondents came from across the sector and included Imperial College London, Nottingham, Exeter, Leeds Metropolitan and Bournemouth universities, Roehampton University of Surrey and Writtle College.

Half said it was too early to estimate the scale of bursaries they would be able to provide. Some 35 per cent were planning to spend up to a third of their fee income on bursaries, while the rest planned to spend between a third and a half of this money.

All respondents confirmed that they intended to charge the maximum £3,000 fee for at least some of their courses.

But more than a third said they would not necessarily charge the same for all courses, with three giving specific instances where a lower fee would be appropriate. For example, Roehampton University of Surrey plans to charge £3,000 for lab-based courses while classroom-based courses will set students back £2,000 a year.

The system of charging according to the cost of provision is well-established for fees charged students from outside the European Union, for which the market is unregulated.

For example, the University of Cambridge charges non-EU students one of three different prices that depend on the cost of the course. Last year, it charged an annual fee of £7,400 for degrees in languages, classics, economics and maths; £9,700 for degrees in engineering, natural science and music; and £18,000 for the clinical training years of medical degrees.

This system is likely to come under pressure as the basis on which the government seeks to introduce increased tuition fees is the earnings premium for graduates rather than the cost of the course itself. For example, it has suggested that, for EU students, foundation degrees should be cheaper than full degrees while acknowledging they cost 10 per cent more to provide.

Imperial College, which charges non-EU students £9,800 a year to study mathematics and £12,600 for most lab-based subjects, said it would consider whether a single fee reflecting the earnings premium rather than the cost of a course would be more appropriate in future.

Many respondents acknowledged that they would charge variable fees while remaining opposed to them.

Mike Goldstein, vice-chancellor of Coventry University, said: "I am personally opposed to the rush into different fees set by different universities as it will increase disparity in educational provision rather than improve equality.

He added: "Universities that attract better-off students will be able substantially to enhance their provision - more and better-paid teaching staff, better library and computing facilities, better social spaces and, perversely, more and higher bursaries - compared with universities whose students will not be inclined to pay higher fees.

"So less well-off students will have a lesser educational environment than the better-off."

Peter Scott, vice-chancellor of Kingston University, said he was opposed to variable fees.

The university would charge £3,000 a year for most courses, he added, but special deals could be offered to students from partner further education colleges and local schools.

Where institutions stand on variable charges

Source: THES . Base: 20 institutions

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login