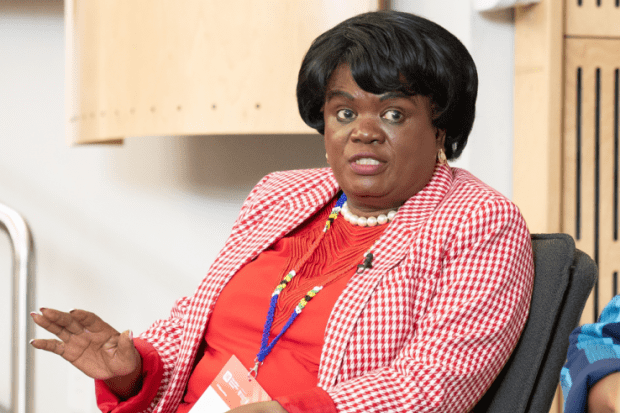

“People were celebrating – not only in higher education but across the whole nation,” recalled Address Mauakowa Malata, vice-chancellor of Malawi University of Science and Technology (MUST), on her becoming the country’s first female university leader.

Public celebrations for a university executive appointment, however historic, are difficult to imagine for many. To understand the reaction, one must consider the incredible odds that Malawi’s women must overcome just to get an education: only 27 per cent of girls are enrolled in secondary education and just 5 per cent finish school, according to a 2022 United Nations report. With only about 8,000 places available each year across Malawi’s six public universities – the country’s population is 20 million – making it to undergraduate level is itself an achievement.

Professor Malata knows about these struggles. No one in her village went to secondary school, except her and her siblings. “I went to school without shoes – I also had to repeat my second year as my grades were poor,” said Professor Malata.

“I travel all over Malawi telling my story and encouraging girls to apply to us – it’s not easy, because we’re a science and technology university, but some students say those talks helped them to keep going, and they’re now studying.”

Campus resource collection: Wisdom from women leaders in higher education

Professor Malata trained as a nurse before taking a PhD at Edith Cowan University in Australia and later returned to teach at the University of Malawi, where she served as principal of its Kamuzu College of Nursing from 2008 to 2015. She joined MUST as deputy vice-chancellor in early 2016 but within a few months was given the top job, vowing to enact radical change and grow the institution, which had been created just four years earlier.

Abolishing the election of deans and heads of department – a legacy from its time within the University of Malawi – proved controversial, explained Professor Malata.

“People who were not committed [to their department] were being elected – not because they were the best candidates, but because they bought drinks for their friends,” said Professor Malata. “I was told people wouldn’t accept this, but it’s now the standard in all of Malawi’s universities.

“We were also the first university to embed entrepreneurship in the curriculum, with students spending at least six to eight weeks in industry. That’s had a huge impact – on graduation day, I’ll often ask students about their plans and many will say they’ve already got jobs lined up,” she continued, adding that one recent graduate had established an agricultural technology company now employing 1,000 graduates. “That kind of thing makes a real difference in Malawi,” she said.

Upending established norms is difficult for any university leader but Professor Malata believes, as a female leader, it might have been beyond her in an older university. “If I’d been appointed to an existing university [with more history] it might not have been so easy – you’d have the faculty, researchers and students to contend with. As it was, I could push through things with this opposition,” she reflected.

With a tertiary education enrolment rate of 2 per cent for men and 1 per cent for women, Malawi’s big challenge is growing its university sector, and doing so quickly. To reach its goal of becoming a lower-middle-income country by 2030, a category whose tertiary enrolment rate is 25 per cent, it will need to have 1.2 million people aged 18 to 24 in higher education, the Malawian academic Steve Sharra has said. At present, only about 81,000 students are enrolled in universities, both public and private.

Professor Malata was, however, optimistic that Malawi’s universities could grow if given the right resources. “We’ve created many programmes that didn’t exist here before I arrived – there was no programme for manufacturing engineering. Now we have one, plus degrees in biomedical and chemical engineering, and in computer systems. In fact, our cybersecurity students have won a competition held in Cape Town, which shows we can build courses to rival the best in Africa,” she said.

Unusually for a science-focused institution, MUST has its own cultural studies department. “At our School of Culture and Heritage, you can study African music,” said Professor Malata, namechecking the east African state’s most widely known export, aside from tobacco, sugar and coffee.

Encouraging more female students into STEM subjects will be one of many challenges that Malawi’s sector faces. “I was the only woman at my university with a PhD, and now we have eight, but it’s still not enough. I know how hard it is to have an academic career and have children – and one of my children was very sick – so I have done a lot of mentoring to help faculty to keep going,”

In March, Malawi appointed another female vice-chancellor – University of Warwick graduate Ngeyi Ruth Kanyongolo, who will run the Catholic University of Malawi – but Professor Malata worried if many more would follow. “I look at the pipeline and do not see many women – my department is mainly men. I do wonder whether another woman will be leading a university in Malawi soon.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?