Leadership is not the same as personal power and wise leadership is far removed from grandstanding and bossiness

Are there any lessons from the study of political leadership that are transferable to education? Leadership depends greatly on context, yet there are illusions that are quite widespread among both political and educational selectorates. One such fancy involves overcompensating for the failings of the previous leader.

It is only a rare vice-chancellor or college head who combines all the attributes desirable in the holder of that office. The same applies even more strongly to the leader of a government or a political party where the problems – or “challenges”, to use the now firmly established euphemism for problems – are more varied and less predictable. As a result, selectorates, whether within universities, Oxbridge colleges or political parties, tend to focus on avoiding the more negative attributes of the outgoing leader when choosing the successor. They likewise hope to replace the departing head with one who appears to have the particular strengths his or her predecessor lacked.

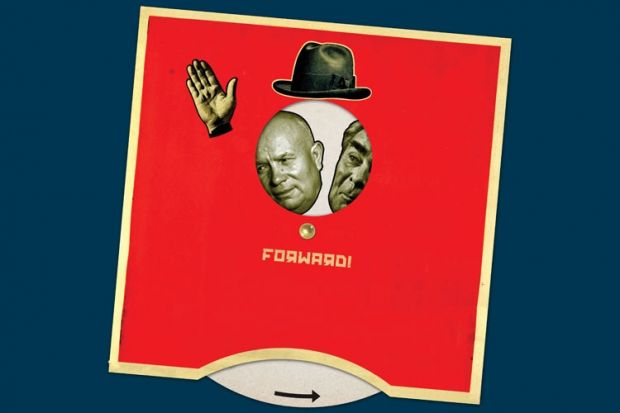

Even the Soviet Politburo did this. The domineering, ebullient, radical but unpredictable Nikita Khrushchev was succeeded by the consensual, cautious and conservative Leonid Brezhnev who, at least within the political and military elite, operated collegially. In reaction against the stagnation of the Brezhnev years and the security of tenure it provided for ageing and even corrupt officials, his successor Yury Andropov shook up the establishment during his brief tenure of the highest office, making extensive personnel changes, before dying after only 15 months in the post. Alarmed by the speed of turnover under Andropov, the Politburo chose as his successor the ailing and colourless bureaucrat, Konstantin Chernenko, who survived for only 13 months before he, too, departed “to join Marx and Lenin”. During his time as Soviet leader, not a single new face appeared in the top leadership team and the only departure from the Politburo came with the death of the veteran defence minister, Dmitry Ustinov.

What immediately followed was a reaction against the stultifying conservatism of Chernenko’s reign and an attempt to get away from the embarrassing consequence of gerontocracy – state funerals of Communist Party General Secretaries as an annual ritual. In Moscow at the time of Andropov’s death it was joked that Margaret Thatcher phoned President Reagan and said: “You should have come for the funeral, Ron. They did it very well. I’m definitely coming back next year.” And so she did – for Chernenko’s obsequies. She had the additional incentive of renewing her acquaintanceship with the newly installed intelligent, energetic and (by the standards of the late Soviet period) young leader of the world’s largest state, 54-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev. Three months earlier, Gorbachev had paid a successful visit to Britain and had even managed to charm the Iron Lady. After their lengthy discussions at Chequers, she famously remarked: “I like Mr Gorbachev. We can do business together.”

John Major, as successor to Thatcher, was yet another example of the successor offering a sharp contrast with his or her predecessor, at least in leadership style. Paradoxically, though, he was also Thatcher’s own choice to succeed her, even though the doubts that she harboured at the time were to intensify in the years ahead. This particular change may well have benefited the Conservatives in the 1992 general election, especially as it paved the way for a retreat from the highly unpopular community charge, commonly known as the poll tax, to which Thatcher had been unwaveringly committed. Labour, however, would have required an 8 per cent swing to win that election and this was always going to be a tall order.

While leaders count for something in every election, it is rare for the prime minister or leader of the opposition to make the difference between a party’s victory and defeat. For parliamentarians in fear of losing their seat, the fond belief that such a change might make a crucial electoral impact can, nevertheless, be a major motive for them seeking a different face at the top. When, in an epic of Australian politics, Kevin Rudd gained revenge for being ousted by Julia Gillard in 2010 by defeating her in an intra-party struggle in 2013, regaining the premiership in June of last year, the opinion poll boost to the Labor Party’s fortunes was exceedingly short-lived. The party was comprehensively defeated in the federal election of September last year. Rudd resigned from the party leadership, and a change that he had instituted earlier – appointment of Cabinet members and (when the party was in opposition) Shadow Cabinet members by the leader – was reversed, with a return to the old system of the top team being elected by the parliamentary party caucus.

There are qualities much to be preferred in the head of any institution than imperious rule or an obsession with projecting an image of strength

There is another, more profound illusion that is often found among those in the business of selecting leaders, apart from seeking to avoid the predecessor’s negative points and sometimes acquiring alternative shortcomings. And that is the search – whether in politics, business or education – for a strong leader, a power maximiser who will confidently take the big decisions and be the overwhelmingly dominant personality within the institution. That, too, may provoke a backlash. And in this case it should. Leadership is not the same as personal power and wise leadership is far removed from grandstanding and bossiness. The American political scientist Hugh Heclo, in a refreshing break with current fashion, has commended the words of the ancient Chinese philosopher Lao-Tzu who said that “a leader is best when people barely know that he exists, not so good when people obey and acclaim him”.

Leaders should not be chosen for their desire and ability to dominate. Those who concentrate decision-making in their own hands, bypassing colleagues and taking credit for the ideas and achievements of others, are not the most admirable of leaders and only rarely the most successful. There are qualities much to be preferred in the head of any institution, or leader of a political party, than imperious rule or an obsession with projecting an image of strength. They include integrity, intelligence, articulateness, collegiality, shrewd judgement, a questioning mind, willingness to seek disparate views, being a good listener, ability to absorb information, good memory, adaptability and vision.

Looking through my file of correspondence with Isaiah Berlin, I recently came across an interesting letter he wrote to me in 1986 about the qualities one should look for in a head of college. Berlin observed that “the most needed qualities in a head of house are justice, kindness, imagination and intellectual power”. To the extent that they do not overlap with the desiderata I have proposed, they should certainly be added.

Educational institutions, like political parties, do tend to look for someone who will be different from (and in certain respects better than) the previous leader. In the case of Oxbridge colleges, this can mean alternating between choosing an academic as the college head and a prominent figure from the greater world outside. At a time when fundraising looms ever larger among the duties that fall to the person who presides over the college’s proceedings, there can be a temptation to think that someone who has made a career outside academia and has widespread influential contacts will be more effective than a mere academic. Often it does not work out like that, since a scholar who really understands and believes in the value of academic work, and can convey a genuine enthusiasm for supporting it, may be more successful in touching the hearts and purse strings of potential philanthropists.

Important though it has increasingly become, fundraising is, of course, only a part of the wide range of tasks confronting a college head or vice-chancellor. In that same letter (not yet published in the volumes of his collected correspondence), Berlin went on to generalise about the appointment of people who were not academics to headships of colleges when he wrote: “I do not believe that outsiders, no matter how eminent, who have been made heads of houses, have proved an unqualified success either at Oxford or at Cambridge.” He made two exceptions – Lord Goodman (“who is an exception to all rules”) at University College, Oxford, and Rab Butler at Trinity College, Cambridge. Goodman was the trusted legal adviser of the great and the good and relied upon by prime minister Harold Wilson, among others. Butler, who had been a student of distinction at Cambridge, had in the course of his long career in Conservative politics held the three greatest offices of state (other than the prime ministership) in British governments – chancellor of the exchequer, home secretary and foreign secretary.

The particular letter from Berlin I have cited was prompted by the fact that the Oxford college of which I was a fellow, St Antony’s, was about to choose a new warden. The college went on to elect at that time someone who ticked a remarkable array of boxes – who came, indeed, with Berlin’s very strong recommendation – and who had made a distinguished mark in both the academic and political worlds. This was Ralf Dahrendorf, who had been researcher, professor of sociology in three different German universities, deputy foreign minister of Germany, European commissioner, and director of the London School of Economics for a decade, while somehow (owing to one, in particular, of Berlin’s “most needed qualities”, that of “intellectual power”) managing to write more than 20 books.

In the period of almost 30 years since then, there have been exceptions other than Goodman and Butler to Berlin’s generalisation about the undesirability of putting non-academics in charge of academic institutions. Yet there is much to be said for this, his broad conclusion: “I feel convinced that unless one has had academic experience for a reasonable period of time, as a teacher or researcher, unless one can function easily and freely as a natural member of the academic world, and in particular as someone involved in college life, then the post of the head of a college is bound to prove, after a short while, tedious, and what seem to be the trivial issues which occupy governing bodies, irritating, to inhabitants of wider worlds.”

Top traits: what are the most important qualities in a vice-chancellor?

We asked a panel of academics and higher education experts which qualities they believe are most important in a university vice-chancellor. Here are their responses.

Amanda Goodall

Senior lecturer in management at City University London and author of Socrates in the Boardroom: Why Research Universities Should Be Led by Top Scholars (2009):

“A leader should be an expert in the core business of the organisation they are to lead. If it is a university then the vice-chancellor should be a top scholar (as a back- of-an-envelope calculation, the vice-chancellor should probably be at least as good a researcher as the top 10-15 per cent in the institution). They should know what good teaching looks like and, of course, any vice-chancellor must have leadership skills and management experience.

“People who have proved themselves in one field (top scholars, for example) may be more likely to suffer from hubris. Therefore vice-chancellors must have humility about the things they do not know. Consult where possible; it makes academics and professional staff feel involved, which cements their commitment to the organisation. Vice-chancellors also need to be strong because they have to be prepared to not be liked by everyone all the time.

“Finally, headhunters often put vice-chancellors into a university post and then chase them to move again, sometimes as soon as two years into the job. University boards must ensure that vice-chancellors are doing what is best for their university, not what is best for their next job.”

Peter Scott

Professor of higher education studies at the Institute of Education, University of London, and former vice-chancellor of Kingston University:

“Napoleon is said only to have wanted lucky generals. This may be apocryphal, but nevertheless this is a good quality for a vice-chancellor. Napoleon certainly did say that you make your own circumstances, and this is also something vice-chancellors should try to do. So you need both great luck and creative vision.

“More specifically, a successful vice-chancellor should see leading a university as an intellectual project not just a management one, although of course universities need to be well run (especially when it comes to money). Most ‘re-engineering’ projects and ‘change agendas’ end, first, in tears and, eventually, in little or no change. Above all, a vice-chancellor should see the academic community as an ally not, as it sometimes seems today, the ‘problem’.”

Stephanie Marshall

Chief executive of the Higher Education Academy and editor of Strategic Leadership of Change in Higher Education: What’s New? (2007):

“For me, jazz is a really useful metaphor for academic leadership, and therefore apposite in considering the most important qualities of a vice-chancellor. An inspirational jazz conductor has the ability to share their vision of what a successful performance outcome and impact should be with all players. They set an appropriate rhythm and pace that allows space for individuals, or a collection of individuals, to take centre stage and demonstrate their own unique expertise.

“At the same time, great insights into the conductor’s unique signature are gleaned as they keep the performance balanced, inclusive and moving forward. Such an approach ensures that everyone stays engaged, and all are ambitious to deliver an outstanding performance. Such ‘leadership’ qualities enable everyone – players and spectators alike – to feel the energy, enjoyment and sense of collective achievement.”

Peter McCaffery

Deputy vice-chancellor of London Metropolitan University and author of The Higher Education Manager’s Handbook: Effective Leadership and Management in Universities and Colleges (2010):

“It is less about an idealised leadership model than the ability to adopt the right approach for the context in which their institution is placed. It is about teams and team behaviour as much as it is about any single individual. It is about the leadership they foster in others. Vice-chancellors come in many shapes and sizes: academic icons, fundraisers, energising visionaries and institutional healers. The perfect model would have strategic vision, expertise in resource management and credibility with the academic community combined with first-rate ambassadorial skills.

“Political and commercial savvy and a stronger client focus are more recent emphases. Humility is an underrated leadership virtue, too.”

Mike Shattock

Visiting professor at the Centre for Higher Education Studies, Institute of Education, University of London, and author of Managing Successful Universities (2003):

“A good university will be full of leaders – leaders in their disciplines and in university affairs. Vice-chancellors must be good listeners, must select from the ideas buzzing around them, put their own gloss on them and articulate them so that they constitute a strategy that their university staffs can stand behind. A vice-chancellor is the conductor of an orchestra, not a tank commander.”

Vernon Bogdanor

Research professor at the Institute for Contemporary British History at King’s College London:

“A good vice-chancellor should be a role model for academics and students. That means that he or she must be someone of high academic achievement. Anyone with a business background, or expertise in ‘management’ or ‘leadership’ should be automatically disqualified.

“A good vice-chancellor will appreciate that the strength of the university lies in its creative talent, the academics, rather than in the quality of the administration. Therefore, he or she should ensure that the top professors are paid more than the top administrators. This can be done either by lowering their own salary below that of the professors, or – preferably – raising the salaries of the academics, so that they are paid more than the vice-chancellor.

“But where is such a paragon to be found?”

Fred Inglis

Honorary professor of cultural history, University of Warwick:

“Answering this question is like rewriting Kipling’s If for the corporate age. Vice-chancellors should first of all be men or women of some intellectual distinction, that is, should have shown in their lives some strong understanding of the highest intellectual principles and dedication. They should also be in themselves clearly men and women of straightness of character, and imaginatively capacious with it.

“They should be accessible and naturally egalitarian, obviously, but also creatures of presence (damned hard to find), entirely their own person and certain not to toady to the more powerful nor ever to accept a knighthood. They should be confidently able to distinguish in their own decision-making between mere impulsiveness and courageous resolution.

“They should be plain and public in their defence of the best idea of a university, and well able to oppose and criticise the transient and trivial ministers briefly appointed to ruin that noble and necessary ideal. If only…”

Mark Pegg

Chief executive of the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education:

“Here are my top 10 tips on the leadership qualities of a good vice-chancellor:

- Wake up every morning knowing how lucky you are to have one of the best jobs in the world.

- Be wise, not just clever – while brilliance is good, experience and common sense are also important.

- Prepare to wrestle with paradoxes – to drive change, but also to conserve the best of the old.

- Know your own mind, but be able to listen and take advice from others.

- Aim to see the value in things, not just the price.

- Reflect and reflect again, but also know when to act.

- Be resilient and very patient but be able to up the pace when needed.

- Know what the university is for, as well as what it is good at.

- Think global but care about local.

- Have a sense of humour, or develop one fast if you don’t have one – you are going to need it.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login