“The monsoons are heavy and cause the flooding of the river, which is when the lack of sanitation is most evident. All of the human waste, animal waste and goodness knows what else literally floods out across the streets, which leads to a lot of disease and illness.”

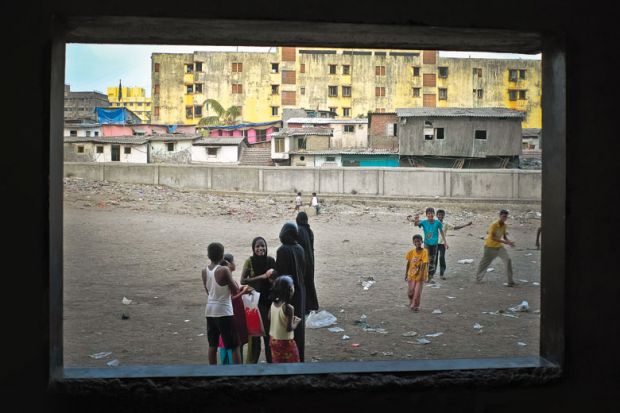

The sprawling shanty town of Dharavi, in the heart of Mumbai, might sound like the least conducive place on earth to set up a series of theatre workshops. But that has not put off Selina Busby, senior lecturer and course leader of the master’s in applied theatre at the Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, University of London. Over the past seven years, more than 50 students have travelled with her to the slum – home to somewhere between 500,000 and a million people – to run a community theatre programme for young people there.

Dharavi gained international prominence in 2008 when it featured in the Oscar-winning film Slumdog Millionaire. Its gritty portrayal by director Danny Boyle was not far from reality: it contains 15 people per 200 square feet, but, according to Busby, it has only “something like one toilet for every 1,440 people” and it loses 13,000 of its children to preventable illnesses every year. However, there is another side to it as well – a “strange but uplifting kind of community spirit, [such that] people genuinely seem to get on with each other”.

Busby’s interest in the area pre-dates the film. About a decade ago, she was talking with Divya Bhatia, an artist and theatre practitioner in India who was already doing a lot of community theatre work, about the possibility of taking a group from the Royal Central School to Mumbai. They had run into each other, in the UK and also in India, while participating in a project that partnered teachers and theatre artists.

Bhatia was “lamenting the lack of applied theatre work and the [lack of] funds for this work in India”, Busby recalls. “He and I work in a very similar way. We use theatre as a means of exploring young people’s identity and community spirit, and as a means of education. The original idea for the project was just to produce a bit of theatre and see how it goes.”

Bhatia’s work with the Society for Nutrition Education and Health Action, a Mumbai-based non-profit organisation that campaigns on behalf of women and children and has drop-in centres in Dharavi, allowed him to reach young people and encourage them to take part in Busby’s programme. About 50 turned up for the inaugural course in 2008, which was run with the help of six undergraduate and master’s students from the London school.

“I was surprised by how many [locals] consistently came every night,” Busby admits. “Lives in Dharavi are quite chaotic – getting a group of young people together at the same place at the same time for two to three days every week is really quite difficult.” Of those initial 50, more than 40 completed the four-week course, and about a dozen return each time Busby comes back. Some have even taken to staging their own theatre productions, and also help to run the “Dharavi Biennale” celebration of the arts. One of the young people who helped out on the first programme, working as a general assistant to Busby, is heavily involved in running the Royal Central School programme. “Now his CV most definitely says he is a theatre practitioner, educator and deviser in his own right,” Busby notes.

Such commitment despite all the hurdles is “one of the most extraordinary things about the project”, Busby says. “It is an aspect of the work that I would not have thought possible when we started, and much of my research is into why this is the case, and why [the youngsters] value participating enough to make the space for it each June.”

Busby’s research currently focuses on theatre that “invites the possibility of change through participatory performance”, and she presented her Dharavi work at the International Federation for Theatre Research conference at the University of Warwick in 2014.

“I am particularly interested in how sustained involvement with theatre can disrupt internalised negative identities, and I am [also] exploring this through research projects with prison populations in the UK and Malta, and homeless youth in New York,” Busby says.

The Dharavi students – who are typically aged between 13 and 18 – often come and tell her what they enjoyed about the project the previous year, and what has captured their imagination this time around. “It is in those one-to-one moments where you see that somebody who is living in very difficult circumstances values the opportunity to play,” she says. “I think that is one of the most important moments of success for me – watching young people who don’t have the time or the space to play, or to be playful, doing just that.”

There are benefits for the UK students as well. “They are training to be drama facilitators, to work in situations with marginalised communities or as drama teachers,” Busby explains. “So they are very much honing their skills and learning what it’s like to work in community settings by actually doing it, not just reading about it.” But it’s not just professional skills that are built up: there is personal growth, too. “Most say it is a life-changing experience. They come back with a stronger sense of humility and of their own privilege.”

Typically, the students arrive a week before the start of the four-week workshop to acclimatise themselves. When it’s in full swing, they facilitate workshops of three to four hours for several days a week, incorporating a range of techniques from storytelling and improvisation to scriptwriting and puppetry. Gradually, a play emerges, which the participants then perform for invited members of the community.

Some years the participants opt for “Bollywood-style performances with romance and action”. But more often than not, they choose to explore an issue that they want their community to think about. This is because drama offers them a “safe space” to discuss contentious issues: they “feel that they can talk about anything”. Among issues they have tackled are homophobia, religious intolerance, sexual inequality and sexual violence against women.

According to the BBC’s 100 Women campaign, an incident of domestic violence is reported every five minutes in India, and more than 300,000 crimes against women were reported in 2013. “The interesting thing for me to watch, as those conversations unfold, is that it is quite often the boys who address that as a concern, and raise it as an issue they want to tackle,” Busby notes.

Despite the worrying crime statistics, Busby says that she and her students feel safe in Dharavi. They stay together in rented accommodation that is only five minutes’ walk from the slum, but is in a “safe and secure” area. However, Busby does recount one particularly hair-raising incident, in the second year of the programme, when students were rehearsing in a multi-purpose building.

“Dharavi works on a 24-hour cycle. Whatever time of day it is, there is always somebody working; there is always a lot of hustle and bustle,” Busby says. “It was about 5 o’clock in the afternoon and there were people sleeping above us because of their particular shift patterns. Drama workshops tend to be quite noisy…and we got some gentle complaints about the noise.”

Much more concerning, however, was the realisation that “a crowd of about maybe 200 people” had gathered outside the building. They “could hear what was going on inside but didn’t understand what it was, and were confused and upset that there was so much noise. They were attempting to come in to stop whatever was happening.”

Busby recalls vividly the moment one of her co-workers opened the shutter to try to calm the situation. “I had a glimpse of what felt like a mob of people coming in to invade our space.”

At that moment, the space “didn’t feel particularly safe, and yes, the Slumdog Millionaire air of violence was in my head”. In reality, however, “it wasn’t anywhere near as dramatic as that” and was merely a symptom of Dharavi’s “problems involving space, more than anything else”.

Despite the huge success of Busby’s programme, she remains modest about its importance. She is “sure there are things we could export to Dharavi that would be more useful on a practical, day-to-day basis”, such as “finding a way to immunise more children against diphtheria or typhoid” or “finding a way to bring in clean water, light and ventilation. But I can’t do any of those things. That’s not what I do. I create theatre.”

The only people who can drive real progress in Dharavi, she adds, are the people who live there. “Theatre won’t make those changes for them,” she says. “But it might create a space for them to talk about things, create things – and think.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: More than just a stage

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?