Human destruction of nature is rapidly eroding the world’s capacity to provide food, water and security to billions of people. That is the dismal conclusion of the most comprehensive study of biodiversity ever conducted, involving more than 550 experts from more than 100 countries.

The research, published in March, was carried out under the auspices of the United Nations-sponsored Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. The name of that organisation suggests that the solutions to environmental destruction are in the hands of scientists and governments – but it is not nearly as simple as that.

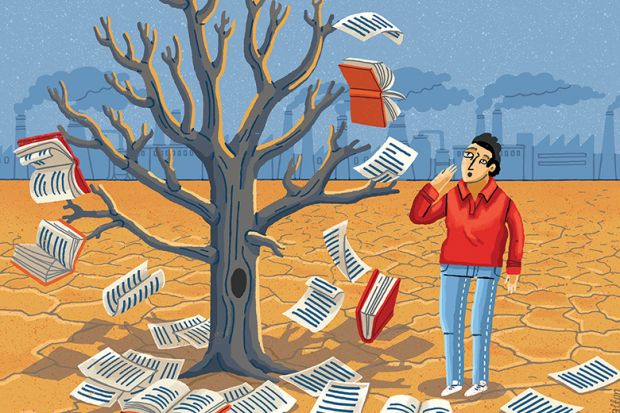

Environmental degradation is, above all, a moral failure. It is a dereliction of our duty towards our fellow living creatures and, at the human level, it usually does most harm to the most vulnerable. Only when humanity as a whole – and governments in particular, working effectively together – accept responsibility for action will the tide of this ongoing man-made catastrophe be turned.

Poets, novelists and dramatists often portray this ethical crisis more powerfully than scientists. It is not just that creative writing communicates, as science does not, the sheer beauty and awe of the natural world: its unspoiled wildness an essential source of health, creativity and freedom. Long before most universities were established, writers also had much to say on what we would now call environmental policy.

In pre-industrial England, Daniel Defoe and Edmund Burke warned of the adverse environmental effects of mining. Subsequently, William Wordsworth expressed outrage at the adverse effects of industry; Fyodor Dostoevsky at the environmental blight caused by urbanisation; Elizabeth Gaskell at the health crisis precipitated by environmental pollution; Henrik Ibsen at the cover-ups that protect vested interests; Émile Zola at the environmental and economic damage done by industry; Anton Chekhov at deforestation as a consequence of poverty and ignorance; Ignazio Silone at the diversion of water sources to serve the interests of rich landowners; and John Steinbeck on the disaster of the Dust Bowl in the American Midwest, largely caused by poor planning and greed.

Works such as Hard Times, Germinal, Uncle Vanya, Fontamara and The Grapes of Wrath raise moral issues that remain painfully live in many parts of the world. These include the need to balance capitalist enterprise with due consideration for sustainability and quality of life; the question of governmental responsibility towards the vulnerable; and the mutual dependence of human societies, resulting in the need to cooperate internationally to halt and reverse environmental destruction.

Some of these writers drew on a training in science: Chekhov as a doctor, for instance; Steinbeck as a marine biologist. And their writing was often a major force in public education. It helped give voice to increasing alarm and anger over environmental issues, and in incalculable ways affected both popular opinion and legislation.

As a fellow at the Center for International Development at Harvard University, I once gave a talk on poverty and environmental damage as reflected in Western literature from 1789 to 1939. Its director introduced me as the first person there to put the case for literature as a source of insight for those who deal with environmental issues in government and scientific bodies – and that is how I got into environmental studies.

This subject – in most universities no more than 20 to 30 years old – nominally welcomes cross-disciplinary approaches. After all, we all have a stake in the future of the environment, so there is an uncommonly strong argument for the avoidance here of intellectual territorialism and interest-driven preoccupations: the bane of government policy. Yet, in practice, the humanities are mostly excluded from environmental studies. The sciences and social sciences focus on scientific solutions to environmental issues, and neglect the human factor.

Scientists are often surprised to learn that the same issues that preoccupy them have long been central to poetry, fiction and drama. Even when they are made aware of it, they are often indifferent. Some seekers of dispassionate truth may even be irritated by the moral passion of literature. For some environmentalists, however, the language of literature rings true. Its outrage is the only honest response to what is happening – and, in any case, moral passion is a much stronger influence on public opinion than dispassionate truth.

Scientists need to learn some of this language, and more people in general need to hear it. For this reason, I believe that environmental literature should figure more prominently in the curriculum, in both schools and universities. England has a profound culture of love and concern for the countryside, particularly in its poetry, yet that hasn’t prevented a steady depletion of most species of birds, bees, wildlife and plants. That literature needs to be read more widely, and its warnings heeded.

But it is not just local or recent literature that is relevant. Although conditions have changed since Gaskell wrote about 1840s Manchester, or Zola about 1880s Normandy, or Silone about the southern Italy of the 1920s, such historical literary attacks on man-made environmental disasters remain powerful wherever you live.

Indeed, some of them already have a permanent place in global culture. But they must be put to better use. They must be taught, accepted and acted on more widely, both within and beyond environmental studies. That way, they could help power a new industrial revolution that, unlike the last one, does not desecrate and destroy but, instead, reveres, guards and sustains the environment.

David Aberbach is professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at McGill University, and is currently a senior research fellow at the London School of Economics.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Leaves of a different kind

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login