What would you do if one of your students asked for academic advice on a course that you didn’t teach? For most, it seems, offering up some words of wisdom doesn’t seem too much of a strain. What if it was a question about your own course but it was 8pm on a Saturday? What if the student demanded an immediate reply? What if they wanted you to map out their essay plan? Or what if they wanted you to advise them on deeply personal issues but you had no mental health first aid training?

Quandaries like this are confronting academics in the UK, US and elsewhere with increasing frequency in an era of high fee-paying, digitally native students who expect instant responses to their problems. This attitude is also being encouraged by politicians who regard students as akin to consumers. In the UK, the universities minister, Sam Gyimah, has called for universities to be in loco parentis to ensure that they are offering students “all the support they need to get the most from their time on campus”. In response, critics have said that this infantilises students when they should be learning to be independent adults.

They also question the burden that it places on academics, and fear a collapse of the boundaries between professional and private life.

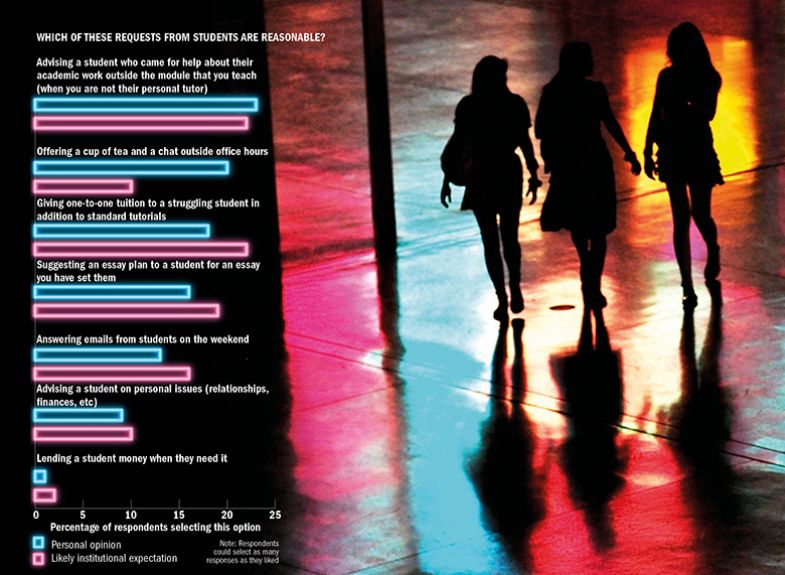

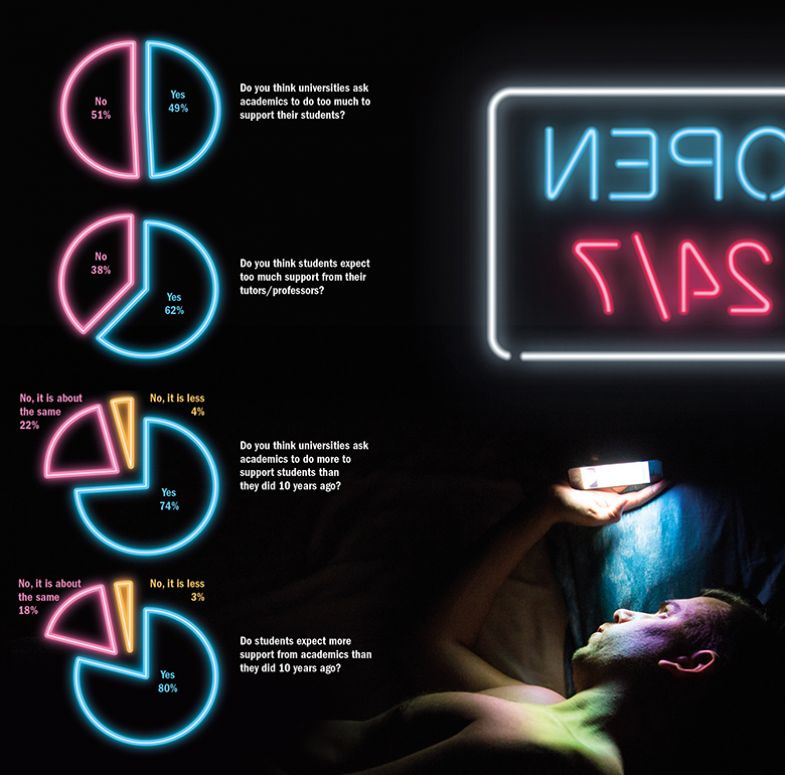

The scenarios sketched above are taken from a survey conducted by Times Higher Education on the subject of academic support for students. It finds that 74 per cent of the 152 respondents feel that universities expect academics to do more to support their students than they did 10 years ago, while 80 per cent report that students also expect more support than they did a decade ago.

Some of the student requests that they report range from the faintly ridiculous – such as urgent queries made on deadline days and demands for responses to emails within 24 hours during the holidays – to the outrageous – including demands to amend a grade “because they got A grades at school” or to “go over all the lecture and seminar content they had missed while off on a ski trip”. One senior lecturer in the UK writes that a student insisted that “I read a book he had written, to ‘understand him’, before looking at his work for assessment. When I said it was not relevant, he then refused to speak to me directly.”

More often, students make requests for help outside office hours. One senior lecturer reports having received an email from a student “at 3am demanding an answer to a past exam question, followed by an aggressive complaint at 7.30am that I hadn’t responded”, while another relates that “my students email me all the time, at all hours of day and night, often about things they could answer for themselves”.

Technology means that emails – and messages posted on social media – are always accessible via smartphones. They can arrive from students at any time of the day, and a rapid response is often expected, academics tell THE.

“It’s undoubtedly true that students now have higher expectations of the sort of support that they might expect than they had in the past,” says Helen O’Sullivan, pro vice-chancellor (education) at Keele University. “There’s this feeling of being constantly available, the blending of professional and private life. A lot of colleagues are on Facebook and Twitter, so how students access academics has really changed.

“The barriers [to accessing academics] are so much lower than when I was a student,” O’Sullivan adds. “If I wanted to talk to an academic, I had to find them in their room.”

A report by the charity Student Minds into student mental health and the role of academics, published in January, found that academics feel that they have “little ability to protect their time and limit student engagement to fixed hours”.

“Emails present a particular challenge,” it says. “Students can send emails at any time of the day or week and often seem to expect a reply outside of working hours.”

So is today’s generation of students less independent than previous ones? They are often portrayed in the media as delicate snowflakes unable to cope with the pressures of adulthood or the stress of a demanding higher education, and some of the answers to THE’s survey lend credence to this view, with 62 per cent of respondents stating that students expect too much support from their tutors.

“Students arrive with the expectation that they will be told what to write in the exam,” says one male senior lecturer from the UK. “They are only concerned about passing the assessment with the highest mark, but seem unwilling to put in even minimal work.”

“Students are less able to manage their own learning,” writes a female senior lecturer. “I think the school system has contributed to this ‘only the right answer will do’ culture. It impedes learning and teaching in higher education.”

O’Sullivan agrees. “There is this perception that students are coming to us less well formed as independent learners, and I suppose that’s probably true,” she says.

“But I’m not sure there was a golden age where students rocked up as fully formed independent learners. It’s just that it was a lot less obvious, because of the way society has changed, the way family dynamics have changed and the way parental involvement is more common now,” she explains.

“You’re more likely to get a parent saying to their child ‘why don’t you go and see your tutor about that?’, whereas, 10 to 15 years ago, students just had to make their own way.”

Early in their courses, universities must instil in undergraduates the concept of developing as independent learners, O’Sullivan says. “We need to make things explicit that perhaps were previously implicit. That’s where the biggest change is going to come in the next few years. Today, there is much more of a sense from the student that ‘I’ve paid my fees, therefore it’s reasonable to ask certain things from my university’ – though, of course, that’s not the whole picture.”

However, the phenomenon is not apparent everywhere. Bret Stephenson, senior research fellow at the Centre for Higher Education Equity and Diversity Research in Australia’s La Trobe University, observes that expectations around student support in the UK and the US are markedly different from those in Australia. “Unlike our English-speaking cousins, Australia does not have a tradition of personal tutoring or academic advising,” he says. Hence, “there are fewer opportunities, relatively speaking, for Australian students to feel that they are being nurtured or over-nurtured by their institutions.”

In the past 10 years, a number of studies and reports have highlighted the very low levels of student-staff interaction in Australian universities when compared with the US and Canada, in particular, he explains.

Instead of a robust and formalised system of personal tutoring, there is a “hodgepodge of often short-lived trial projects aimed at offering more targeted support to students in need”, he says. Some universities will build intervention programmes aimed at particular demographic cohorts – such as first-in-family students, Stephenson explains, whereas others use learning analytics to identify when academic intervention is needed, such as failure in an assessment. “But very few, if any, of these programmes are anything like what students in the UK would recognise as personal tutoring,” he says.

Some respondents to THE’s survey believe that the pressure on academics in the US is higher than in the UK. “I have taught in the US, and students there expect much more from their lecturers – too much, in my opinion,” says Megan Davies Wykes, a lecturer in engineering at the University of Cambridge.

One American male professor in the social sciences writes that “students have increasingly become less independent. Rather than struggle with intellectual questions for a while, they more quickly seek an answer from the professor.”

Darren Linvill, associate professor at Clemson University in South Carolina, says that it is “certainly true” that student expectations around pastoral and academic support are higher now than when his father was a college professor. “Just because a student has an expectation, however, doesn’t mean we are required to honour it. It is up to faculty to establish clear rules of the road with their students,” he says.

“There is certainly a perception among many faculty that the commoditisation of higher education has changed the faculty-student dynamic and…not necessarily for the better,” Linvill adds. However, student expectations in the US vary hugely depending on the type of institution – private or public, research- or teaching-focused, large or small, he adds.

In the UK, the near-trebling of most undergraduate tuition fees in 2012 was a watershed moment for student expectations, according to several of our survey respondents. Asked why modern students expect more from academics, one respondent sums it up in a single word: “Fees.” “Expectations are mismatched with the reality of higher education learning,” he continues. “As consumers, students expect a ‘service’ without really knowing what that ‘service’ should look like.”

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, believes that the UK’s “boarding school model” of “higher education away from home” – which differs from that in countries where students attend their local institution – contributes to the sense that universities must offer more support. “Academics were up in arms about Gyimah’s comment about in loco parentis, but it has some truth to it – even if not perhaps in the way that he meant it,” Hillman says.

“Technically, we say that people are adults at 18; but in terms of student finance, we don’t treat them as adults until they are 25,” Hillman says, referring to the age at which parental income often ceases to be relevant for student support. “It certainly adds to the confusion about how independent they are.”

Understanding that university is, for many undergraduates, a period of transition before adult life proper begins is helpful for everyone, he continues. “Institutions have a duty of care to people who do not feel that they are fully formed adults – it’s not about mollycoddling, it’s about helping them make that jump to independence.”

Some scholars, however, believe that the pressure on academics to fulfil outsized expectations comes from above, not below. Roger Seifert, professor of human resource management and industrial relations at Wolverhampton Business School, says that it comes “from senior managers, rather than students”.

Although academic support for students has not changed in its nature, it has changed in its intensity, Seifert says. “Pastoral care has become more embedded in all activities, and administrative burden – such as uploading essays, marking reviews, tutorial times – has grown rapidly and to our detriment.”

Academics are also keenly aware of their universities’ desire for good results in comparative sector-wide exercises such as the teaching excellence framework and the National Student Survey, one female UK lecturer says in her survey response. The NSS, which feeds into the TEF, puts the emphasis on student satisfaction, and the pressure to do well is high among UK institutions. “There are a bunch of additional duties of a pastoral nature being demanded of the academics despite institutions’ having dedicated professional student services available,” she says.

Gregor Gall, a former professor of industrial relations at the University of Bradford who is now an affiliate research associate at the University of Glasgow, agrees that “the demands on academics are now greater than at any time before”.

“The trajectory of increased student demands on staff as a result of students’ being consumers of higher education – as a result of paying fees – has been added to by technological developments. It is leading to intolerable pressure on staff, because they are almost inherently predisposed to want to help students, but often without seeking increased resources to do so,” says Gall, who believes that universities must make clear to students what they can rightly expect in terms of response times, so they do not unwittingly besiege staff.

O’Sullivan agrees. “[Universities] have a duty of care towards our students but also a significant duty of care to our staff. If you are an academic answering loads of emails from students at the weekend, that’s going to be incredibly stressful and put a lot of pressure on you.”

And while it is “not unreasonable for today’s students to expect that instant response”, universities need to “help academic colleagues understand different ways of working and how to put barriers in place. We probably don’t do that as well as we should across the sector,” O’Sullivan reflects.

Eunice Simmons, deputy vice-chancellor of Nottingham Trent University, agrees that staff feeling that they have to reply instantaneously to student requests is “counterproductive for the staff member’s well-being, but also for the student’s preparedness for the world of work”.

“Just because we have instant communication does not always mean that an instant response is appropriate or necessary – that’s the same in the workplace. It makes everything feel as if it needs to be solved and resolved now, but that’s really unhealthy.”

Immediate replies might also be less considered and constructive, argues Simmons, with messages taking on an “exasperated, last-minute” tone rather than the more reflective and thought-through nature expected from academics.

“Tutors have to plan when they are going to be available for responding – they should be actively working that out in their week, because otherwise everything becomes very rushed,” she says. “We’ve got some very fine tutors here, but I need them to be able to focus predominantly on the academic support to students to ensure that [the students] achieve their best.”

With this in mind, she says, Nottingham Trent is developing a programme to encourage effective personal tutoring. “But we do not agree that staff should be on hand 24/7,” Simmons says. Indeed, knowing “when to step back and let the student do things for themselves is a huge part of [tutoring]”.

According to Ron Iphofen, a former director of postgraduate studies at Bangor University, “you have to begin with a kind of nurturing attitude, but then gradually students need to learn to be independent.” This approach is much easier at a postgraduate level, however, because at undergraduate level “you simply don’t have the time” to do this for each individual student.

Encouraging traditional independent learning has become “increasingly complicated” now that the internet affords such easy access to information, Iphofen adds. Independent learning is no longer about spending hours in the library searching for the right text because now the desired information is at students’ fingertips. “They expect different things, and that is why it is challenging to be a good educator these days; you have to move with the times otherwise you miss understanding how your students learn.”

Supporting the learning of students working unsocial hours presents a particular challenge for academics. As many universities’ libraries are now open 24/7 and are packed late into the evening, the solution could be user-friendly digital resources. Indeed, O’Sullivan says, Keele is now looking at 24-hour support that is less heavily reliant on academics “because obviously there’s a limit to what you can provide around the clock, so it’s important to set expectations of students”.

Replies to frequently asked questions should, for instance, be placed online because “it’s not reasonable for an academic to be answering the same question from 70 students individually”, O’Sullivan says.

Keele is keen to help “our academics to wean themselves off that sort of personal support, where it could be better provided in another way, and then saving our academics for where their intervention is really valuable is important”, she adds.

The importance of drawing boundaries regarding student support is a key theme among responses to our survey. On the question of what is reasonable to offer students, many academics state that the scenarios cited (from offering extra one-to-one tuition to lending a student some money if they were desperate) are unacceptable. “I maintain a very firm boundary,” writes one female engineering lecturer.

However, most survey respondents admit that extending extra support to students is an inevitable and often positive part of the job. The problem for many is that the additional work it involves is poorly recognised by their employers.

Many survey respondents indicate that they regularly go beyond what their institutions expect of them, with offers of cups of tea and biscuits whenever students want them, phone calls if they are unable to attend campus and even extra tutorials.

Those staff who are perceived as approachable, often women, are most likely to find themselves with bigger workloads related to pastoral care, says the Student Minds report. But such work also exacts an emotional toll, and that should be recognised by institutions as well, it adds.

“This emotional labour may be asked of all staff, but it’s usually expected as a given for women, particularly junior ones,” says Hannah Murray, a teaching fellow in early American studies at King’s College London.

The blurring of the line between academic and pastoral care is clearly a huge part of the issue. One interviewee in the Student Minds report explained that they had “started getting way over-involved, I had a student who had lost housing and I said I’d be her guardian”.

The paper adds that there is a lack of clarity about the exact meaning of the term “pastoral”. “Our participants expressed the view that academic and pastoral responsibilities cannot be easily separated as academic problems almost always have a non-academic cause,” the report says. It explains that the confusion around role boundaries was felt to be structural and maintained at an institutional level. Many academics feel that they are being asked to perform tasks that are beyond their remit and for which they are not equipped, Student Minds adds.

The report recommends that academics receive active support to “understand, maintain and communicate appropriate boundaries to their students”, online and on campus. “Communications to students from their university should reaffirm these boundaries,” it concludes.

Boundaries and support are especially difficult issues when it comes to student mental health. Many respondents to THE’s survey feel that they are the “front line” when it comes to students’ psychological well-being, and while, overwhelmingly, they wish to help, they have no expertise to deliver mental health advice.

“There can be an expectation that we offer pastoral support that goes beyond academic mentoring, and we are not trained to carry out this role,” explains Charlotte Burns, a professorial fellow in politics at the University of Sheffield.

That is not to say that students in need should be turned away, but rather that academics should direct them to the appropriate university support services, says Simmons at Nottingham Trent, who adds that it is imperative that institutional signposting is kept up to date. “Some of the help that students need is more than just the common-sense answer, so the correct action by the tutor is to help the student track down the expert advice they need.”

Academics need to know their university and the services on offer so that they can steer students to the right place quickly and accurately, she says.

“I get the sense that some tutors feel that they have to be everything and do everything…but they can’t give [so much],” Simmons adds.

However, guiding students to the correct service is useful only if the support is actually available. The number of first-year undergraduates reporting a mental health concern has increased fivefold in the UK in the past decade, according to a report last year from the IPPR thinktank. However, universities have reported growing waiting lists and overwhelmed support facilities. Student services need to be well resourced, and the communication between the services and academics improved, Student Minds says in its report.

“Mental health services within and outside higher education are woefully underfunded, so there is often nowhere for the students to go beyond your immediate support,” Murray of King’s explains. “I have counselling training, but I am not a mental health professional.”

Another female lecturer “once had a suicidal person ring me daily, but my institution could offer me no support in coping with being a helper other than an outsourced phone line. I was fine in myself, but I need to talk, share and get reassurance, and there was nothing to help me help them.”

Her experience echoes that faced by thousands of academics across the world, who feel an urge to assist students seeking help but also recognise that an element of self-preservation is critical.

“Academic staff need support to support students,” she says. “We don’t mind being the voice of help, but we need time and space to help properly and to take care of ourselves in the process.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The on-call academy

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login