In the summer of 1968, when I was living in Portland, Oregon, I responded to an advertisement recruiting English teachers for historically black colleges in the American South. As a result, I was offered a lectureship at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, founded by Booker T. Washington in 1881, and one of the most prestigious of such colleges.

Loading my books, old lecture notes and German Shepherd dog into my Volkswagen Beetle, I set off on the 2,500-mile journey from Oregon. As I crossed from Mississippi’s black macadam to Alabama’s pale concrete highway, a large sign greeted me: “Welcome to the George C. Wallace White Way. 873,000 Alabama Baptists welcome you.” I drove on south through Montgomery, Alabama’s capital, where the Confederate flag flew beside the state house.

Tuskegee was a small town with just over 11,000 residents, of whom more than 90 per cent were African American. Thanks to gerrymandering and the refusal of votes to its black residents, it was governed and policed by its small white minority. In 1966, Sammy Younge, a student activist at the Tuskegee Institute, had been shot for attempting to use the “whites only” bathroom in a local gas station. His murderer was acquitted by an all-white jury and continued to run his business.

Most of the students came from the southern states and many had witnessed or borne the brunt of the violent response to demonstrations for civil rights and the integration of schools. They had chosen to come to Tuskegee because of its high status but also because they had often been made to feel like outsiders in newly integrated secondary schools still dominated by white teachers and pupils.

Those experiences, and the assassination of Martin Luther King, led many of them to embrace the ideologies of Black Power and Malcolm X. The prevailing mood was a mixture of anger, pride and determination to move forward. The young men and women were beginning to wear Afros (despite the disapproval of their parents and teachers). James Brown’s Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud echoed in the student halls, along with the music of Aretha Franklin and Otis Redding.

I was a white teacher in a college where 98 per cent of the students and staff were black. Yet this was not my first experience of being part of a minority defined by others. My Indian grandfather had been described in Australia, where I grew up, as “black”. In the context of the “white Australia” immigration policy, my family kept silent about this ancestry, which was well concealed by my Scottish father’s dominant genes. Nevertheless, I remained preoccupied by questions concerning assumptions about national, cultural and racial identities and how they affected my own identity.

Now, however, I found that I was regarded as a spokesperson for white people. One student told me how, on her journey to Tuskegee, she had asked for a cup of coffee at a recently desegregated cafe and the waitress had spat in the coffee before pushing it towards her. “Why do white people behave like that?” she asked me.

Students would give fiery speeches about the need to send all “honkies” (whites) away, and then come to my flat to eat with me and argue about whether Tom Jones or any white singer could be said to have “soul”. We would consider whether, despite being built on the profits of slave labour, southern mansion houses could be considered beautiful, and whether it was absurd for young black women to sympathise with Scarlett O’Hara’s plight in Gone with the Wind (as some did). We discussed Frantz Fanon, Negritude, the Black Panthers, non-violence, Malcolm X and racial categories, including the absurdity of the 1/32 rule that classified anyone with just one black great-great-great-grandparent as “Negro”. What intrigued me was the double awareness that such categories had to be affirmed rather than denied in the face of white racism, even though they were constructed and ridiculous. These students felt a profound need to build a strong black racial identity in their own terms.

I was sometimes reminded of the categories laid down in the Irish Catholic convent school I had attended in Australia, where it was taken for granted that English Protestants were cold, materialistic and lacking in spirituality – in contrast to the warmth, sympathy and depth of religious feeling that supposedly characterised the Irish. Such comparisons between Irish and English, black and white, African and European, helped me understand how racial categories were political constructs rather than biological givens. I also learned that a number of Irish writers, especially J.M. Synge, James Joyce and W.B. Yeats, had profoundly influenced black writers during the Harlem Renaissance, and later in Nigeria and the Caribbean.

The issues I discussed with the students who came to my house were also raised in the classroom.

Soon after my arrival at Tuskegee, I discovered that the head of the English department, although herself of mixed race, regarded writing by African Americans as inferior. She had deliberately recruited young white northern teachers to offer the students a traditional Anglo-American curriculum and to encourage them to speak with northern accents and idioms. Yet it was clear that this was not at all what most students wanted. So I garnered reading lists of African and African American writers from black professors and I sat in on special seminars they offered the senior students. In addition to discussing works by Sophocles, Shakespeare and T.S. Eliot, I discovered, with my students, Ralph Ellison’s tale of a Tuskegee-educated man’s search for identity in Invisible Man, the precolonial African world depicted by Chinua Achebe, and the passionate eloquence of James Baldwin.

Because of its prestige in the African American community, Tuskegee hosted an extraordinary variety of artists and celebrities. They included Muhammad Ali, opera star Leontyne Price, Chinua Achebe (speaking about Biafra), the Modern Jazz Quartet and Nina Simone. Never before or since have I witnessed such ardent appreciation among young audiences for contemporary poets, who drew on the idioms and rhythms of African American speech. Students were inspired to write and recite their own often powerful and witty poetry, some of which was published in the plethora of small African American magazines that had suddenly appeared or by Broadside Press, a radical publisher based in Detroit.

My original plan had been to teach at Tuskegee for a year and save enough money to take up a doctoral fellowship at the University of California, Berkeley – to write about medieval Icelandic sagas. But the discovery of African American and African literature, and its impact on the students at Tuskegee, made me completely change direction – and shaped my whole subsequent career. I stayed for two years and then wrote to 25 universities proposing to study for a PhD in such literature. Twenty-four of them replied that this was not a substantial enough topic. Fortunately, Cornell University not only encouraged my choice but also offered a three-year fellowship.

By the time I had completed my doctoral dissertation – a comparative study of African, African American, Caribbean and Irish cultural nationalist movements – in 1973, there had been a dramatic change in attitudes. I was offered numerous interviews, many on the assumption that my specialty and teaching experience meant I was a black woman and therefore eligible for double affirmative action points for the universities concerned. As I entered the interview room, I would see mingled surprise and dismay on the faces of the interviewers. Eventually I was appointed an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts, one of the first northern universities to set up a black studies department, and where Achebe was a visiting professor.

Although I taught Irish literature at Massachusetts, I also sat in on and sometimes co-taught Achebe’s courses in African literature. Almost all the students were white, and from the contrast between their responses and those of the Tuskegee students to novels such as Achebe’s own Things Fall Apart, I realised the importance of acknowledging differing readerships and audiences. At Tuskegee, students identified with and admired the warrior protagonist, and also noticed the play on the connotations of different languages. The white students tended to read the novel as an anthropological document and would ask for more information about Igbo customs and rituals.

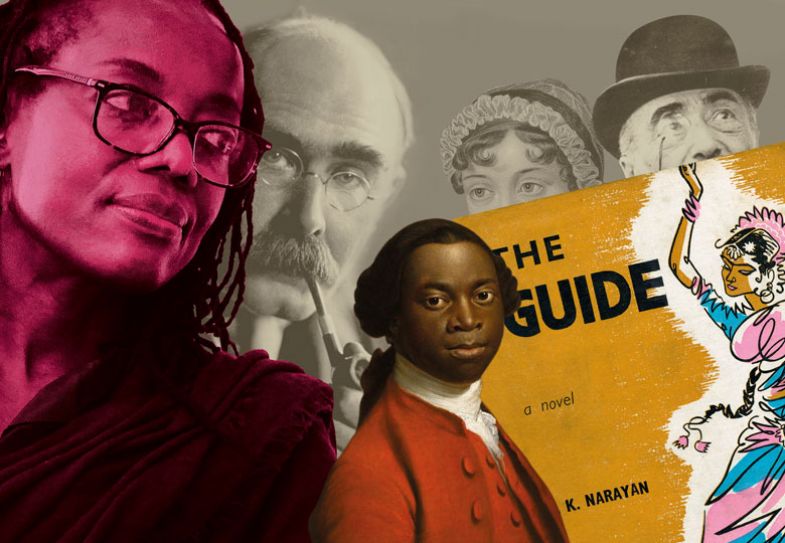

In 1974, Achebe gave a landmark public lecture, whose arguments still echo through today’s debates, where he denounced as racist Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (one of the most commonly taught novels in American English departments). Many of my colleagues were outraged, although Achebe later stressed that censorship was not the answer. His assertion that works such as Conrad’s needed to be taught in the context of African as well as European history and read from a variety of points of view led me and other colleagues to create courses that placed novels by writers such as Jane Austen, Rudyard Kipling, E.M. Forster and Conrad alongside works by Olaudah Equiano, Salman Rushdie, R.K. Narayan, Achebe, Tsitsi Dangarembga and Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

At the University of Kent, where I moved in 1975, I was able to teach Irish literature as well as African and Caribbean studies. The latter degree, which included interdisciplinary courses in history and literature, attracted many students whose parents had emigrated to the UK from Africa or the Caribbean, but also many white students. Indian literature and history became an additional element in the 1980s.

So what lessons would I draw from all this in addressing the fresh calls to decolonise the curriculum, sparked by the impact of the Black Lives Matter movement in the wake of George Floyd’s killing earlier this year?

I believe there is a crucial need for all students, both black and white, to engage with the writings of black and Asian authors. Tuskegee showed me the remarkable impact that the encounter with African and African American writers had on black students: the importance of reading works in which their own worlds, colour, cultures, stories and speech were the norm rather than an exception. Moreover, these writers create a range of characters who are both individual and representative, eschewing the stereotypes and limited roles that are common in works by white authors. Their works encourage the creativity and confidence of younger writers to see themselves as part of a growing community speaking to more diverse audiences.

Yet this is only one side of the coin. It is equally crucial for white students to encounter other worlds and other perspectives, and to see how creatively the English language and traditional literary genres can be transformed to represent those worlds.

Curricula must now acknowledge that there is a very substantial body of literature, going back to the 18th century and beyond, written in English and other languages by African, African American, Caribbean, black British, Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan and Asian British writers. In the 20th and 21st centuries, these writers include many winners of the Nobel literature, Pulitzer and Booker prizes. Fortunately, there are now a number of scholarly studies that provide surveys and discussions of the relevant writers. The excellent Cambridge History of Black and Asian British Writing, edited by Susheila Nasta and Mark Stein, is a recent example.

What is equally important, however, is to integrate black and Asian writing and perspectives into more general literary anthologies and histories. This occurs to some extent in the vast collections produced in the US, but, in the UK, poetry, drama and short fiction by black and Asian British writers still tend to be confined to separate anthologies. Most histories of English (or French or German) literature published during the past 50 years tend to ignore writers who are not of English (or French or German) descent, or at best provide a brief paragraph on Salman Rushdie or a chapter on “immigrant writers”. Ignatius Sancho (c.1729-80) corresponded with and commented on the works of Laurence Sterne. Oloudah Equiano (c.1745-97) was just one of many ex-slaves who wrote powerful autobiographies. Yet they are absent from most literary histories and from genre studies of autobiography and biography. Similarly, surveys of 19th- and early 20th-century British writing generally ignore the perspectives of African and Asian authors on imperial assumptions and culture.

There is also an important element that distinguishes black and Asian writers from their white counterparts. They generally bring to their works what the pioneering black sociologist W.E.B. DuBois and British academic Paul Gilroy have both spoken of as a double consciousness – the capacity to see oneself through the eyes of others, as well as from the perspective of one’s own community. This capacity is akin to what the Ghanaian-British philosopher Kwame Appiah describes as cosmopolitanism – a wide-ranging awareness of more than one cultural perspective and a creative interplay between those perspectives. For Gilroy and Appiah, cosmopolitanism implies not just appreciation of other cultures and peoples, but must embody an understanding of the political relationships and historical factors that influence our assumptions about those cultures and peoples.

This cosmopolitanism is surely something that teachers and scholars should nourish in their students, together with a fuller understanding of Western nations’ complex cultural history.

Lyn Innes is emeritus professor of postcolonial literatures at the University of Kent, Canterbury and the author of A History of Black and Asian Writing in Britain (2008).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Making the curriculum more cosmopolitan

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login