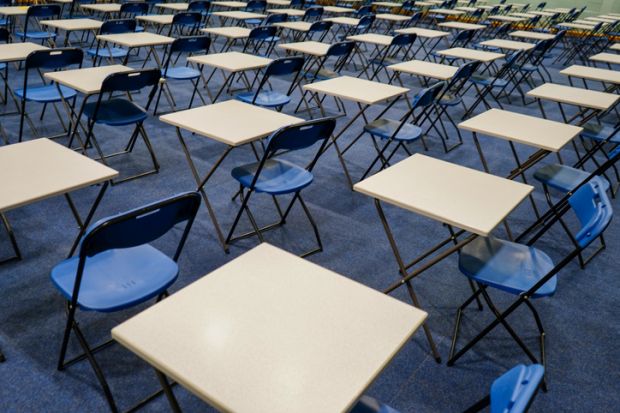

When undergraduates can turn to AI chatbots to write their essays, calls for a return to in-class testing will surely grow louder. Closed-book exams are now, some argue, the only way to guarantee academic integrity and fairness.

But it would be wrong to forget why UK universities have moved away from traditional examinations in recent years, even if they continue to be used for at least part of many degree courses.

First, there are the logistical challenges of exams – whether held in person or online. Exams require space, online or in person, that is accessible and closed so that students cannot collaborate. In a physical space, this extends to surrounding areas to make the exam conditions silent. In an online exam, students must find their own space, which is good because it means that students who don’t respond well to silence can listen to music.

But what about the students who do not have reliable internet access or a quiet space to study? These students and those taking in-person exams will often require extra time or special technology, meaning that they will have to self-declare their need to receive the appropriate resources.

Invigilation is another issue. To provide the resources to maintain integrity and to make available the required assistance for students with additional needs can be costly. Staff are required for invigilation in all exam rooms – an increasingly onerous task given the myriad ways to cheat. Access to phones, smartwatches and, in the not-too-distant future, glasses may need to be restricted.

Staff must also create questions and develop marking rubrics that can cover all the different needs outlined. These rubrics will ensure that all papers are marked to the same criteria and without bias.

For remote online examinations, the task is arguably harder. When social distancing during the pandemic meant that students were not able to congregate in a large exam hall, many questions emerged about how to maintain academic integrity while sitting an exam online. One big challenge was geographically distributed cohorts, which meant that exams were held multiple times in different time zones. That required several different papers, which in turn meant that students sat different exams, raising questions about the equity of the process.

Accommodations will also need to be made for students who cannot attend the exam at the specified time because of illness, caring commitments or financial obligations, thus requiring further resource. Of course, inclusive education is not just about students, so adjustments might also be required for the staff involved in the process.

Once all these factors are considered and supposed solutions are found, then an exam might seem to be inclusive while also maintaining academic integrity. Except it isn’t.

Those students who have asked for special circumstances are the ones who have the support or the confidence to other themselves by asking for help. It is likely that there will be others who do not, and they will be disadvantaged by the process.

Exams themselves are born from an education system that is biased towards a specific type of learning. Students who have come through certain sections of the UK education system will be better trained in this method and will therefore enjoy an advantage over students who have come from a different system.

There comes a point when you must consider if retrofitting the status quo with more accessible and inclusive overlays is the right way to go, or if you should perhaps just start again.

Furthermore, testing students’ ability to demonstrate their learning in a closed context is not preparing them for a professional future in which technology is ubiquitous. There are few, if any, contexts in professional life that require you to remember information in a specific time frame.

A truly inclusive assessment is one that allows students to use the tools available to them in a real-world scenario, one that permits them to use their own skills and to adapt in a personal way to whatever is going on around them. In such an assessment scenario, no one needs extra time, no one needs to other themselves, no rooms need to be booked and nothing needs to be banned.

Siren calls to return to old-school testing should be resisted and more sophisticated assessment considered. Exams should be scrapped.

Katie Stripe is a senior learning designer at Imperial College London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?