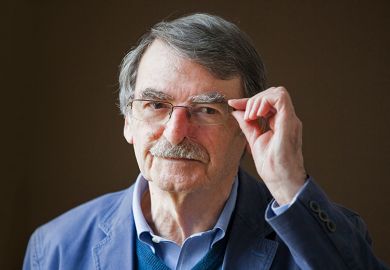

David Lodge was, in his own words, a “cradle Catholic” who lost his Catholicism and a serious writer who became a comic one.

The latter shift came partly at the urging of fellow author, Malcolm Bradbury, who would become a friend. One of his best-known novels, Changing Places, was turned down by three publishers but made its way into print in part because of Bradbury, only for it to go up against Bradbury’s The History Man for the Yorkshire Post Book of the Year Prize. Lodge won and used the £150 prize money to buy an automatic dishwasher. The prize was presented by Lord Longford, who had only read the novel on the train and was so shocked by it that Lodge recalled an ungracious speech and having to tear the cheque from Longford’s hands.

He and Bradbury were so close that a fellow writer invented a place called Bradbury Lodge, although there was also certain rivalry. Once, a power cut meant that Malcolm lost several pages of his new novel on his computer, at which David’s wife, Mary, whispered: “Don’t gloat.” Mary could be sharp and was a practised ironist.

Born in 1935, at five Lodge found himself sent to a convent boarding school, his mother only returning to collect him after 10 days. He later suggested that this was the cause of the fact that in later life he got “anxious about everything”, the writing of fiction a kind of therapy. Though his father was a mostly self-taught musician who had left school at 15, he was also an enthusiastic reader, directing his son to Dickens. Later, Lodge would adapt Martin Chuzzlewit for television.

Following grammar school, he went to university at a time when fewer than 4 per cent of school leavers did so. On his first day at University College London, he met Mary, who thereafter would become the first reader of his novels, he taking her objections seriously, she not hesitating to offer them. At UCL he read Ulysses, which he later regarded as one of the crucial intellectual experiences of his life: that and Lucky Jim. Scarcely out of the same box, these two books were equally relevant to his later career.

Two years of National Service seemed to serve no military purpose, Lodge’s hatred of tanks and cavalry officers making him a poor fit for the Royal Armoured Corps, but it did result in a novel, Ginger, You’re Barmy (1962). Arriving at the University of Birmingham (which would become Rummidge in his novels), he met Bradbury, whom he credited with urging him to develop comedy in his work following their collaboration on a revue featuring Julie Christie, not then a star.

A spell at Berkeley in 1969 led to Changing Places (1975) and Small World (1984). The Catholic writer had become a campus novelist. These were followed by Nice Work (1988). Lodge was a serious man who wrote comic novels, a somewhat staid individual whose books tended to be full of sex to the point that his wife said she was loath to visit the local butcher, who seemed a fan for the wrong reasons. Admittedly, they lived across the road from someone in Birmingham who styled herself as Miss Whiplash.

In other ways, though, Lodge’s own experiences fed into his novels. His time in therapy led to Therapy (1995). The deafness, which forced him to retire from his Birmingham professorship and from giving readings (until a hearing aid resulted in his return to literary festivals), gave us Deaf Sentence (2009), which also reflected his father’s early-stage dementia.

In time, he felt he had used up his own experiences and wrote Author, Author, based on the life of Henry James. Unfortunately, another writer, Colm Tóibín, chose this moment (2004) to publish his own novel about James. Asked why they were both drawn to the émigré American, Tóibín thought that it was because both he and Lodge had suffered the trauma of being sent away as children, so that perhaps James’s sense of exile and solitariness in moving to England struck a chord. The success of Tóibín’s novel, which Lodge felt had scooped his own, made Lodge at first hesitate to publish A Man of Parts (2011), based on the life of H. G. Wells, in case he was scooped again.

As a writer, Lodge would keep copious notes and print out every page 15 or more times until he was satisfied, needing to see his text on the page rather than on the screen. This was the kind of attention he brought to his critical work, publishing The Art of Fiction in 1992, one of a series of books about writing. The critic Lorna Sage may have said that literary theory is where common sense dies, a conspiracy disseminating ignorance, but for Lodge it was fascinating, and he wrote about it lucidly even as his enthusiasm for it declined.

Lodge wrote for television and the stage, was a shrewd critic and compelling novelist. He wrote three autobiographies and picked up awards in this country and abroad. Eventually, though, like Iris Murdoch, Doris Lessing, Terry Pratchett and, indeed, Malcolm Bradbury’s wife, Elizabeth, he succumbed to Alzheimer’s, that frightening spiritual cul-de-sac.

Is dementia worse for writers? Plainly not. Yet their loss of words, the loss of their skill at inventing identities as their own thins to transparency, has an added irony even though their voices can still be heard in their books, as can David Lodge’s.

Christopher Bigsby is a novelist, biographer and emeritus professor in American studies at the University of East Anglia.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?