When US education secretary Betsy DeVos announced in August that she would rewrite the Title IX rules on campus sexual assault, former education secretary Arne Duncan called foul. “Instead of building on important work to pursue justice,” he rebutted, “they are once again choosing politics over students, and students will pay the price.”

Duncan was disingenuous, however, to claim that his Obama-era team did not choose politics over students. Under that administration, the effort to reduce sexual assault on college campuses was so politicised that it became difficult to address the actual cases of alleged misconduct. In its January 2014 “Renewed Call to Action”, the White House Council on Women and Girls declared that sexual assault happens on college campuses because the “culture still allows it to persist”. Colleges had already been put on notice, by 2011’s “Dear Colleague Letter”, that their reputations would suffer if they didn’t strain every sinew to change their “rape culture”.

As with other anti-crime campaigns that serve larger political demands, such as the War on Drugs, colleges’ need to prove themselves tough on crime corrupted due process and overshadowed the facts. Individual cases, which should have been handled with sensitivity and fairness, were made to serve greater institutional needs.

Not surprisingly, the accused suffered under this political pressure, but they weren’t the only victims. In a 2016 article in the Kansas Law Review, titled “Anti-Rape Culture”, feminist law professor Aya Gruber described how “women students, months after an incident, decide[d] to file a report because they talked to a counselor, professor, administrator, or activist who help[ed] them determine an ambiguous or barely remembered sexual situation was actually a traumatic rape”. Under pressure to change the culture, employees pushed students to report incidents that in previous times might only have encouraged self-reflection.

Fortunately, DeVos’ rewrite of the rules, published in late September, provides more flexibility in how institutions handle Title IX complaints. Rather than mandate the lowest burden of proof, “preponderance of the evidence”, the new regulations permit colleges to return to the mid-level standard of “clear and convincing evidence”. Mediation, which had been prohibited under Duncan, is allowed when all parties agree. And, finally, no longer must each teacher be a mandatory reporter of sexual assault. Where the Duncan guidelines said “must”, DeVos’ say “may”.

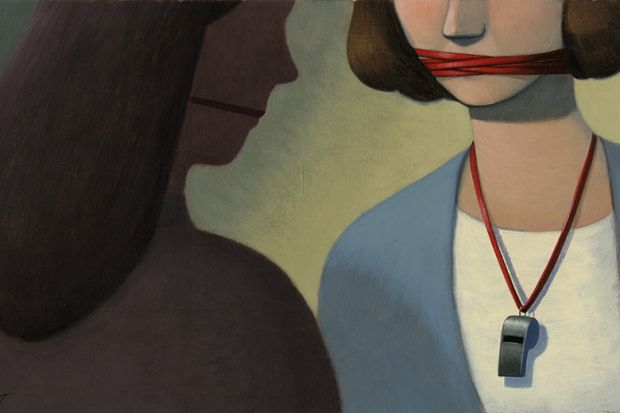

However, it may take a while for campus employees to break the habit of defensiveness. Each September since 2011 we have been indoctrinated as “responsible employees”, and trained to see criminality in the most ambiguous situations. We have been told that teacher-student conversations are not confidential and that, by law, we are required to report anything that smacks of sexual impropriety. For six years, this was the rule and we obeyed.

As a teacher, I was required to police first-year papers for evidence of non-consensual sexual encounters. If an advisee attempted to share her confusion after a dorm party, I was compelled to interrupt her before she said anything incriminating. If she wanted to speak without pursuing a complaint, I had to refer her to one of the few confidential sources on campus: a mental health counsellor or a “survivor advocate”. She and I could not talk openly since I was obliged to share any damning details with the authorities.

One could argue that it is better that a professional counsellor should address students’ distress about sex than a political theorist. But political theory, like other disciplines in the humanities and social sciences, asks students to think about the hidden forces that compel their actions. Some of those are erotic, and political theorists investigate how sexual desires further political interests.

Before the old guidelines, I might have asked students to grapple with the ambiguities of sexual encounters. For instance, if we were reading Simone de Beauvoir’s chapter on sexual initiation, we might have considered the many confusing and contradictory thoughts and feelings involved. Once I became a mandatory reporter, however, I needed to change the syllabus, since any hint of trauma would trigger an investigation.

While the new guidelines now permit colleges to reduce the number of responsible employees, these improvements won’t be embraced as long as the Obama administration’s original charge hangs in the air. As long as campus activists convince the public that any relaxation is evidence that colleges do promote a rape culture, few institutions will take advantage of these liberties. It certainly serves activists’ interests to make that assertion, but it hasn’t served the interests of students.

Contrary to Duncan’s claim, the new guidelines do not play politics with students. Colleges are not pre-judged for condoning a culture that promotes sexual assault. Fairness and impartiality are given greater attention than they were in the older guidelines. We’ve been given greater latitude to address the real problem of sexual assault on college campuses, one case at a time. But will we be courageous enough to try out these new liberties – or will we stay crouched in defence?

Meg Mott is professor of political theory at Marlboro College, Vermont.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?