I have tried not to write about Brexit recently. Really tried.

It often feels as though a brain-sucking parasite has descended on post-referendum Britain (its name is Boris Johnson, I hear the wags cry). If Brexit means Brexit, it also means everything else that the country should be getting on with being cast aside, or commandeered for a proxy Brexit war.

But as the prospect of a disorderly exit from the European Union looms (trade secretary Liam Fox now says a “no deal” departure is likely), it is worth reflecting again on how crucial close alliances with the rest of the EU have been to the astonishing success of Britain’s universities.

Writing in the Independent last week, Venki Ramakrishnan, the Nobel prizewinning president of the Royal Society, pointed out that one in six academics in the UK is from elsewhere in the EU and that 60 per cent of the country’s internationally co-authored papers are with EU partners.

Without a deal, we could lose about £1 billion a year in EU research funding, or about a tenth of the UK’s yearly public spending on research, he added.

This scientific embrace – and the exposure of UK science to any future disruption – is further illustrated by the most recent grants awarded by the European Research Council.

For early career, starter grants, as reported by Times Higher Education last week, the UK is in second place behind Germany, measured by the total number awarded (67 compared with Germany’s 76).

Look at the nationality of the grantees, however, and the UK falls to sixth place (with 22 British grant-winners – fewer than Germany, Italy, France, the Netherlands and the Republic of Ireland).

Of those 67 bringing ERC starter grants into the UK, 50 were from elsewhere in Europe or the world.

This cosmopolitan picture is not quite as pronounced for advanced grants: here, the UK led the pack, with 66 grantees, compared with 42 for Germany and 34 for France. Of those 66, about a third were international researchers (whether from continental Europe or further afield).

In summary, the UK’s university system is highly internationalised – far more so than most of the rest of the world – and this is a major contributor to the outstanding quality of its research output.

Universities, of course, understand this well, and have been ardent proponents of retaining close association with Europe, as well as the rest of the world.

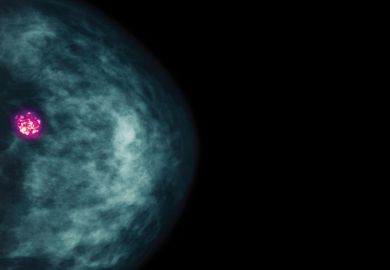

This is not just about international outlook and values, important as they are. It is also about helping to cure cancer, if we are to put it in the populist terms that are so fashionable these days.

There are examples of universities taking steps that may help to limit the damage if the scholarly allure of Britain declines in the coming years.

In our news pages this week, we report on a plan being considered by the University of Oxford to create a new college with a largely postgraduate focus – which could bolster the flow of fledgling researchers in a post-Brexit future.

In our cover story, meanwhile, we consider the state of one of the most high-profile areas of science – cancer research – with perspectives from six leading scholars from the US, Australia and the UK.

The complexity of tackling what is not one disease but 100 different diseases is clear in their reports from the front line.

What is equally plain is that, like most of the world’s major challenges, the key to significant progress is science unshackled by political interference and interruption.

Back in 2013, when he was mayor of London, Boris Johnson gave a speech in which he called on the UK’s capital city to forge a future as a pre-eminent world centre for higher education and research.

It should strive, he said, to be “a cyclotron of human beings…a critical mass of talent”. If that version of Boris had stuck, perhaps Britain would not be in its current mess. But research transcends politics. It is vital that science isn’t thrown under the Brexit bus.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Keep Britain great

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login