This summer two distinctive educational initiatives have been thrust into the limelight. First came the news that China’s Yiwu Industrial and Commercial College has developed a degree programme for aspiring influencers; the curriculum includes modules on “aesthetic cultivation”, “make-up modelling” and “public relations etiquette”. Then, US technology magazine The Verge profiled the LA-based SocialStar Creator Camp, a 10-day programme that promises to transform fresh-faced teens into social media stars.

Such initiatives are perhaps unsurprising at a time when we’re routinely assured that fame and success are just a few selfie uploads away. But they testify to a wider shift in tertiary education, spurred on by the demand to prime students for the so-called digital reputation economy. And, increasingly, research faculty are also prodded to engage in this same sort of online impression management.

Although academic endeavours might seem far removed from the whimsy of YouTube or the filter and curate culture of Instagram, there are striking parallels. I first began to notice these while conducting research on bloggers, vloggers and Instagrammers aspiring to “make it” in a hyper-competitive online economy. Over the course of my interviews, I learned that many of the same ideals that animate academics – independence, flexibility and the perennial quest to do what one loves – also propel the labour (much of it unpaid) of social media hopefuls.

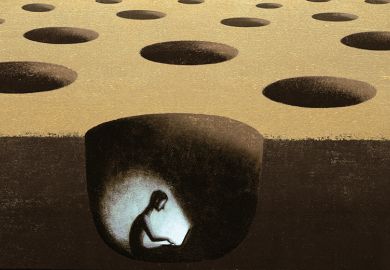

Then there are the less flattering similarities between academic work and careers in social media: the long hours, unpredictability and an over-reliance on contingent labourers. There’s a gap between the promised land of tenure and the precariat in academia, and I found a similar gulf among social media labourers. Instagram influencers may hold dream jobs, with jet-setting lifestyles and six-figure salaries, but there’s a much larger subset of digital content creators who make nary a headline. And there are similar doubts about how meritocratic the sifting is.

I also noticed that both fields issue the same get-ahead imperative, packaged as advice on personal branding. Among the social media aspirants I interviewed, self-promotional activities are pervasive: content is fashioned to be on-brand, posts are timed to coincide with spikes in platform usage and feedback from followers is monitored with vigilance. “Exposure” and “visibility” are driving commands when you’re constantly cautioned that you’re only as good as your last tweet or ’gram. The enterprising young women I spoke with (yes, nearly all were women) see themselves – to borrow business guru Tom Peters’ phrase – as the “CEO of Me, Inc”.

As a junior scholar, I am well acquainted with the need to promote my research. Online guidance about branding oneself and “How to Curate Your Digital Identity as an Academic” is rife. Hence, I feel compelled to keep my website updated and disseminate my publications across a sprawling media ecology that includes Facebook, Twitter, Academia.edu, ResearchGate and more.

Alongside the emphasis on self-branding is an effort to metricise. Social media producers cite their blog reach, Twitter followers and Instagram engagement, while scholars bolster their cases for tenure with evidence of their citations, h-index and journal acceptance rates – which, increasingly, are themselves promoted through a robust social media network.

Of course, academic self-branding occurs offline as well (just as it does for social media workers). Our research speciality is our niche, and the academic elevator pitch we diligently hone is our slogan. This pitch shapes our introductory interactions at academic conferences, post-lecture receptions and other informal hybrids of labour and leisure that scholars call “compulsory sociality”.

I’m also keenly aware of the movement of this self-branding mandate into the classroom, as part of the so-called “professionalisation of social media”. College students are counselled that strategic self promotion is instrumental for standing out amid an oversaturated talent pool, and universities across the US offer courses on personal branding.

But as the self-branding imperative becomes more pervasive in our roles as both scholars and teachers, we should pause to consider the intellectual consequences. As I learned from my interviewees, self-promotion takes a great deal of time and energy (and also economic capital). I’ve personally experienced unease about these redirected energies. Is it affecting my scholarship? And I wonder whether I should continue to prod PhD students to create websites and blog about their research. Is it really the best use of their time?

I’m reminded of an interview I conducted with a fashion blogger who offered a deft appraisal of the extent to which the culture of self-promotion had effaced the more creative aspects of her work. As she explained: “[Even if ] you’re the best, if people don’t know you’re the best, it doesn’t really matter; you just have to be good enough...and well marketed.”

As teachers we must encourage our students to think critically about the self-commodification imperative. And as scholars we must ensure that being well marketed never becomes a substitute for high-quality research.

Brooke Erin Duffy is an assistant professor of communication at Cornell University. She is the author of (Not) Getting Paid to Do What You Love: Gender, Social Media, and Aspirational Work (Yale University Press).

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Do we have to tweet?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login