Since the lifting of the cap on student recruitment in 2015-16, UK higher education has shifted from being a sellers’ market, in which students worried about getting into their desired degree programme, to a buyers’ market, in which students are seen as consumers with an increasing amount of choice.

Statistics suggest that a higher number of 18-year-olds are applying to university as a percentage of total applicants: they account for 53.5 per cent of all applicants in 2018, compared with 49.8 per cent in 2015. And the number of 18-year-olds participating in higher education is increasing despite the fact that the total size of this demographic group has decreased by 3.2 per cent over the past decade, according to the Office for National Statistics.

Students are increasingly free to “trade up” to higher tariff institutions in this new market, in which institutional brand trumps programme choice. If we take the top 10 highest-tariff institutions, we see that they took almost two and a half times as many 18-year-olds as the 10 lowest-tariff institutions in 2017. In terms of raw numbers, the gap has widened by another 1,400 since 2015 because of a 15.4 per cent drop in student numbers at the lower-tariff institutions.

Such institutions have also seen a decline in the number of students over 21 years of age that they enrol. But that total dropped by only a comparatively modest 3.4 per cent between 2015 and 2017. The total number of students over 21 at the 10 lowest-tariff institutions stands at 10,730: more than three times the 3,005 at the 10 highest-tariff institutions – and, just as significantly, 40 per cent more than the 7,605 18-year-olds that lower-tariff institutions have recruited.

A number of lower-tariff institutions are reaching such low levels of traditional applicants that they are being sustained by the over-21 market. Indeed, some – such as the University of Bedfordshire – have adopted a deliberate strategy to move away from targeting 18-year-olds.

Although there is a recognition of this situation in the sector, what is less understood is the effect it will have on such institutions in the longer term.

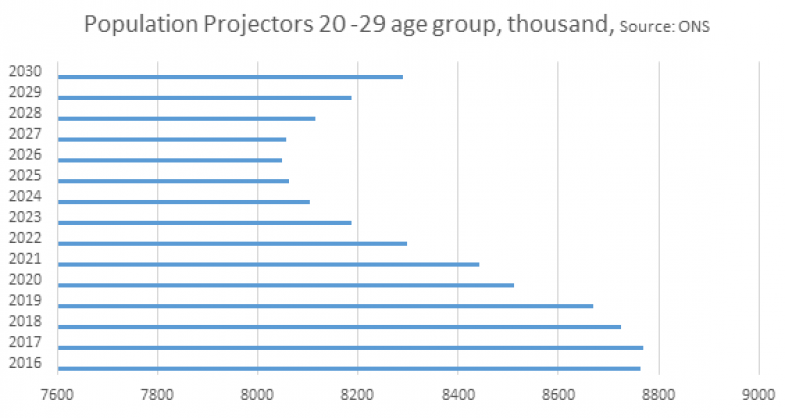

The declining number of 18-year-olds in the UK will, over the coming years, translate into shrinking numbers of 19-, 20- and 21-year-olds. The number of 15- to 19-year-olds will begin to rise again around 2020, but the cohort of 20- to 24-year-olds will not bottom out until 2026, while 25- to 29-year-olds will take until 2030. This means that between now and 2026, we will see a progressive decline in the total number of students between the ages of 20 and 29.

To add to low-tariff institutions’ woes, the supply of alternative post-secondary options is growing: examples include alternative providers, shorter academic boot camps, apprenticeships and a disruptive digital learning ecosystem via education technology. These could be particularly attractive to mature students, who are often unable to commit to higher education full time.

Moreover, if universities allow themselves to be branded as institutions primarily for mature students, they will struggle to tap into the market for 18-year-olds when it returns to peak numbers in 2022. And while mature students may appear less likely to trade up than younger students, lower-tariff institutions would be unwise to rely on this trend given that the tariff is widely seen as a proxy variable for value. As a larger proportion of the population receives higher education, there may be an ambition among the first-generation graduates who were low-tariff institutions’ typical market for their children to acquire degrees from institutions seen as high value.

If lower-tariff providers really want to continue to remain strong, they would be better off reinventing themselves. One idea would be to focus on digitally native Generation Z students or on the emerging cohort of lifelong learners who are not pursuing a first degree but, rather, seeking a technologically convenient way to keep up with an evolving employment market, as machine learning begins to take over some graduate careers.

A change of direction now might eventually put lower-tariff institutions in the front of the pack, rather than struggling to manage decline.

Nora Ann Colton is director of education at UCL’s Institute of Ophthalmology and Moorfields Eye Hospital.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Demographic deficit ahead!

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login