It’s the year 2036, the end of the first cycle of 10-year R&D budgets in the UK. The incoming science minister has the task of assessing whether they have delivered on their promised benefits.

Did they help deliver on the government’s missions, such as growing the economy and making the UK a clean energy superpower? Has industry investment been leveraged at scale? Is bureaucracy lower? Has career precarity for researchers decreased?

It is already clear that 10-year budgets – Labour’s flagship election pledge on science – will not be adopted across the whole public R&D portfolio.

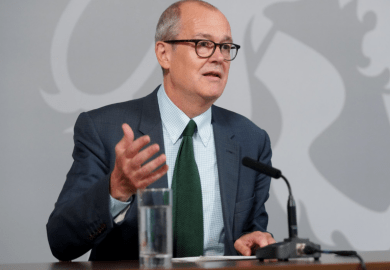

“We have done extensive consultation on which areas would most benefit from 10-year funding. It is not every area,” the current science minister, Patrick Vallance, told the House of Commons Science, Innovation and Technology Committee last month. Only areas where 10-year budgets would make “a big difference”, he explained, would receive such funding.

The identity of those areas is just one of many unanswered questions about Labour’s science funding policy. Others include: Can a funding commitment exceed a parliamentary term? How can long-term funding ensure both agility and stability? How will accountability and inflation be considered?

Various precedents provide some hints, however. On the time frame question, the research councils already make funding commitments well beyond the time frame of their three-year budgets – and across parliamentary terms.

A good example is the National Quantum Technologies Programme, a 10-year, £1 billion programme established in 2014 in partnership with the National Physical Laboratory and Ministry of Defence, among others. The public investment in it leveraged substantial private sector investment, such that by 2023, only the US had more quantum companies and more private investment in them.

Both Vallance and science secretary Peter Kyle believe that this kind of joint public and private long-term investment in R&D is key for delivering against Labour’s R&D missions, to which an initial £25 million was pledged in the chancellor’s autumn budget.

One of those missions is advancing healthcare – and a key related challenge is to tackle antimicrobial resistance. The required advances include developing novel materials, therapies and diagnostic and surveillance techniques. But those breakthroughs won’t happen without a community of trained scientists.

UCL’s centre for doctoral training in engineering solutions for antimicrobial resistance aims to support the development of that community. It has extensive connections to national and international partners, boosting pathways to impact and post-PhD career opportunities. Such targeted investments in skills could feature as part of a coordinated collection of investments within an overarching research programme with a 10-year budget.

The national quantum programme is an exemplar. It has trained almost 500 PhD students, generated 49 start-ups and led to the establishment of the National Quantum Computing Centre near Oxford. Several countries have copied its model.

Longer-term grants come with a welcome side effect: reducing research bureaucracy. The trade-off, recognised in the Tickell Review published in 2022, is that these grants are subject to less accountability.

So how can we get the balance right? Some UKRI programmes involve “stage-gating”, whereby continued funding is awarded subject to review at defined time points in the programme. For example, the Medical Research Council’s new suite of Centres of Research Excellence will be funded for 14 years, with a midway renewal point.

Stage-gating also mitigates another challenge of long-term funding: the increase in research costs over time, driven by inflation and other unforeseen changes. Vallance has indicated that a “10-year funding [budget] would in a sense be a floor, not a ceiling, because otherwise there would be a real problem there”. The renewal point could be used to increase the budget by more than inflation if the political and economic climate permits.

And researcher precarity? We know short-term contracts for researchers can negatively affect researchers’ well-being and prompt talented people to seek better job security outside the sector. That perverse incentive could be minimised by 10-year investments in hubs, programmes and centres, allowing universities and funders to offer longer positions to early career staff. An example is the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council’s future manufacturing hubs, established through seven-year investments.

Although stage-gating would mean research career stability (or industry co-investment) would not be guaranteed beyond the renewal point, 10-year funding frameworks must retain a level of accountability and a balance between committed and agile funding. There must be room for responsiveness to new ideas and opportunities, reducing the risk of funders’ appetite for “risky” research areas diminishing. Trade-offs would be inevitable.

But while 10-year budgets are not a panacea, we have enough evidence from current policy to show that longer-term funding settlements can make a positive difference. Vallance’s successor in a decade’s time is likely to thank him for seeking to end the short-termism that has held back so many parts of the UK’s research sector.

Grace Gottlieb is head of research policy at UCL, where Matt Davis is director of research facilitation and coordination.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?