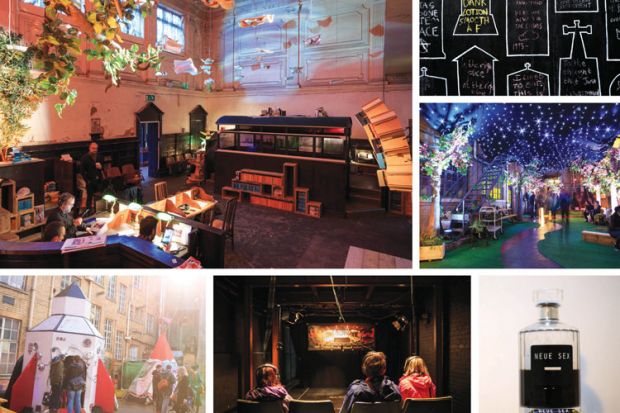

There were many strange things to be seen when “a three-day festival of arts, humanities and new ideas” took over the complex consisting of Bristol’s old fire station, magistrates’ court and police station earlier this month.

In a pop-up cemetery, people chalked up their preferred epitaphs: “She got shit done”, “A plot at last” or “Here be maggot food”. A specially created library featured initiatives exploring the future of the book, while a bedroom gave people an opportunity to design their own “intimate objects”.

Outside in a playground and enchanted garden one could find a rocket, a wonky Wendy house and a swing that put on a dramatic lighting display as soon as one sat down on it. Inside the buildings, one could visit a little theatre to listen to recorded memories of actors, audiences and staff at the Bristol Old Vic.

Meanwhile, far more harrowing was the makeshift clinic where one could hear the testimonies of women and men who had been forcibly sterilised in Peru during the 1990s.

The Rooms festival showcased a total of about 50 projects. All were created by academics and creative businesses, usually working in digital technologies, and nurtured and supported by REACT (Research and Enterprise in Arts and Creative Technology).

Covering the South West and Wales, this is one of four Knowledge Exchange Hubs for the Creative Economy that received £16 million in funding from the Arts and Humanities Research Council for the period 2012-16. The partner organisations which compose REACT are the Watershed media centre and the universities of the West of England (UWE), Bath, Bristol, Cardiff and Exeter.

The projects may have proved very entertaining for those who went to see their interactive installations in Bristol, but how do they serve the goals of the academy and creative economy?

“Technology, academics and creative businesses are an interesting mix and may not be doing the kind of things you expect them to be doing,” says REACT director Jon Dovey, professor of screen media at UWE.

“The whole point was to create a new network of relationships. There are a whole lot of academics across the five universities and a whole lot of people in creative businesses who now know how to talk to each other, have interesting ideas in common, and can create projects or bids to make an impact in the world.”

As an example, Dovey cites a project titled Ghosts in the Garden. Steve Poole, associate professor of social and cultural history at UWE, joined forces with the Holburne Museum in Bath and the team at a company called Splash & Ripple (who describe themselves as “architects of extraordinary adventures”) to create “an audio geo-locative game”. The game summons up the characters who once haunted the Sydney Pleasure Gardens, which occupied the site where the museum gardens are now.

“[Steve] hadn’t done research on those gardens,” explains Dovey, “but he knew how to get to the assizes records and the kinds of archive that would allow the project to turn up some excellent material they could use for narrative content. He also had a really exciting approach for thinking about heritage, exploring what contemporary historians have to offer the heritage industry.”

“We were very conscious of moving away from a model of knowledge transfer,” adds Dovey, “to something even beyond knowledge exchange, a much richer sense of creative collaboration.”

Memory boxes and listening projects

The process can lead to a number of positive outcomes, he says. “A product might get commercialised and start earning money for people. A tiny start-up with two people out of a master's programme might find themselves stabilised enough to be able to continue into a business future. Academics writing new research bids or new teaching programmes often come away from us saying: ‘I teach differently now, because this has been such an interesting experience. It turns out I’ve enhanced my promotion prospects.’”

The projects to be seen in Bristol covered themes ranging from teleportation to risk-taking, fabulous beasts to the future of cemeteries. Two of the most striking involved reaching out to disadvantaged groups.

Debbie Watson, reader in childhood studies at the University of Bristol, has been researching the “life story books” that social workers are required to create for children who have been adopted, explaining how they ended up in the care system.

Since these books are written by professionals, they often contain huge gaps, even when children still have memories of their birth families, and they obviously cannot incorporate any objects. For the “trove” project, Watson, a colleague and designer Chloe Meineck have been developing “a digitally enhanced memory box” where children can store their precious toys and trinkets tagged with audios where they describe the memories attached to them.

The boxes themselves are being co-designed, says Watson, by a group of children who want them to seem like “treasure chests from the future which have been sent back to look after their objects”. The current versions are “precious and futuristic and bespoke” and non-gender-specific. Once the development process is complete, the team hope to launch the boxes as a commercial product, perhaps initially aimed at adoptive parents and adoption agencies.

Meanwhile, the Quipu Project represents a collaboration between academics at the University of Bristol, a technologist and Chaka Studio, an independent production company based in London.

They set out to create “a transmedia documentary telling the story of forced sterilisations in Peru in the 1990s”, says director Rosemarie Lerner. These were targeted largely at indigenous rural women, about 300,000 in all, as well as 20,000 men, and often carried out in insanitary conditions owing to the high quotas set.

“We began working with some of the women who have been fighting for justice for almost 20 years,” says Lerner. “They want an apology from the state, reparations and medical help. Since they have no access to the internet or mainstream media, we decided to create a simple interactive phone line automatically connected to a website: ‘Press 1 to record a testimony or 2 to listen to others.’ We used that device to create a collective story and allow people finally to hear what happened.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: An Aladdin’s cave of wonders

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?