How can developing countries pay for infrastructure development?

How can developing countries pay for infrastructure development?

Alberto Asquer

Alberto Asquer is director of MSc Public Policy & Management (on campus and distance learning) and MSc Public Financial Management (on campus and distance learning) programmes at the School of Finance and Management at SOAS. In this blog post, he introduces ideas that can be studied in more in detail within the core and optional programme modules, including: public debt, infrastructure development, taxation, and market exchange.

One of the issues that was discussed at last week’s G20 summit in Buenos Aires referred to the worrisome increase of public debt that developing countries have made to finance infrastructure development.

According to data from the China-Africa Research Initiative of the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, China extended about $143 billion to African governments and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) over the period 2007-2017.

China’s funds have supported several infrastructure development projects in the continent. However, they have also raised concerns from the side of international organisations like the IMF and African countries alike about the sustainability of African governments’ finances and their dependency on Chinese creditors, which might reverberate into geo-political effects.

Why have African countries made such debts?

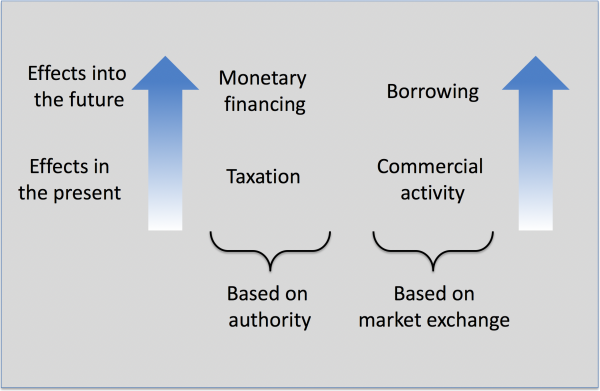

Public debt is just one among various ways in which governments may raise up revenue. A simple way to map out the options available to raise up finance for a government is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 draws a distinction between ways to raise up finance through means of authority (such as levying taxes) and of market exchange (such as commercialising public services).

Another distinction made in Figure 1 is between ways to raise finance that produce effects into the present or also into the future – possibly, for a number of decades. Raising finance through loans, for example, is a way of funding the public sector by market exchange means (the loan is serviced and returned) and with effects into the future (depending on the number of years over which the loan is serviced and repaid).

How can developing countries pursue alternative options to fund the development of their infrastructure?

On the authoritative means side, they may rely on taxation – although in practice tax revenue is typically too low (for many reasons) to allow governments to pay for investments.

Another venue is monetary financing, that is, to print money to pay for the development work – although this venue is typically barred because of the fragile conditions of developing countries’ monetary system that make them prone to risk of hyperinflation.

It is on the market exchange means side, then, that developing countries look at. Borrowing provides financial resources that can be invested into development work. Alternatively, forms of commercialisation of public services – possibly combined with forms of capital financing like in the public-private partnerships (PPPs) – can also help attract capital while servicing it through the revenue from infrastructure services, like for example highway tolls and airport fees.

Making debts is one main tool to kick-start the expansion and upgrade of transport, energy, water and communication infrastructure. Concerns with debt overhang should not be easily dismissed, however. Infrastructure development that stimulates economic growth would result in greater fiscal capacity to service and return borrowed capital. Debt gets harder to be repaid, instead, when money is invested in assets that are not needed, or are poorly designed, or whose construction costs escalate with detrimental effects to the financial sustainability of development projects. African countries should be concerned with the growing debt as much as with the choices that are made about how the money is spent.