Creating artificial lakes in water-stressed countries

Sponsored by

Sponsored by

Researchers at UAEU are collaborating with Abu Dhabi Municipality to develop sustainable solutions for rising groundwater

For up to 10 months of the year, the lowlands of Abu Dhabi are under water. The fast-expanding capital of the United Arab Emirates is not the only city in the region that struggles with rising groundwater levels. The ponds that develop can be several square kilometres in area and up to 7m in depth.

“This is a common problem in many cities, such as Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait City, and other cities in the Gulf,” explains Mohsen Sherif, a professor in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department and Director of the National Water Center (NWC) at the United Arab Emirates University (UAEU). “It depends on the geological conditions of the area and whether they allow irrigation water to penetrate into the aquifer.”

This is the problem that the researchers of the NWC and experts from Abu Dhabi Municipality have been investigating to resolve. The NWC is part of the UAEU and specialises in groundwater, surface water, desalinated water, treated waste water, and environmental issues. It conducts multidisciplinary research and offers consultancy services to government and industry.

Water is one of the UAE’s priority areas because, even though it struggles with rising groundwater levels, it is a water-stressed country. Groundwater accounts for the majority of its water supply, with the rest coming from desalination plants or treated waste water.

However, the rising groundwater that is the source of Gulf cities’ pooling water is caused by irrigation and possible leakage from water networks. These accumulate above some impermeable soil layers so are not reaching the aquifer. In addition, the problem is aggravated in the coastal areas where the shallow aquifer is noticeably thin and the bedrock is shallow and impermeable, says Abdel Azim Ebraheem, a water resources adviser at the NWC and a former consultant with the Ministry of Environment and Water. “This is mainly happening in the coastal areas.”

Water used to irrigate neighbouring agricultural land or green areas in the city percolates down through the topsoil but hits an impermeable layer of clay. The excess water accumulates on top of this layer over time – helped by sporadic and often heavy rainfall – until it begins to form large ponds above the surface.

In some areas, this is a simple matter of pumping this excess water into the storm water system. “But in some locations, these drainage systems are not available and to construct a new system would be very expensive,” says Professor Sherif, who has spent more than 30 years of his career working on the hydrology of groundwater. He joined UAEU in 2001, having previously worked in Kuwait, Egypt and the United States. He is also an associate editor of the Journal of Hydrology and the Journal of Hydrogeologic Engineering.

The experts of the NWC at UAEU have developed two solutions for the Abu Dhabi Municipality.

The first one, Professor Sherif says, involves drilling a number of shallow wells around the affected areas, pumping out the trapped water and reinjecting the collected water, under gravity, to the deep aquifers. This sort of technology is common in oil explorations, an area in which the country has extensive expertise in academia and industry. The shallow wells for pumping the water would have depths of less than 25m, while the deep wells to inject the water may reach 1,200m below the surface. Depending on the area, this solution would cost about 5 million Emirati dirhams (nearly USD 1.4 million), he says.

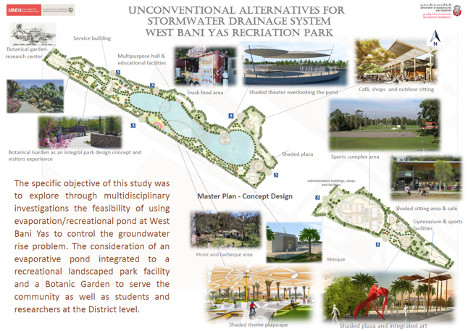

However, the second solution is the one that excites Professor Sherif: use the excess water to form artificial lakes in newly built recreational parks and botanical gardens. “This would allow the excess water to become a source of recreation rather than a problem,” he says. In order to maintain the lake, the water would have to be pumped and circulated so that it does not become stagnant and foul. This solution has a price tag of about 9 million Emirati dirhams (about USD 2.45 million).

None of this research and neither solution would have been possible without collaboration, he says. While Abu Dhabi Municipality is leading the project, other government departments – such as the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company and Environmental Agency of Abu Dhabi provided information on the characteristics of the aquifer. “Without them, how would we know that we have to drill to 1,200m to discharge the collected water?” asks Professor Sherif. “The oil industry has a good understanding of the subsurface geology of the country up to about 10km.”

These are the types of collaborations that the UAE government is pushing. “The government is now really putting a lot of emphasis on collaboration with universities in the country in order to utilise the available expertise and resources, especially in areas of national priorities,” Professor Sherif says. These include water, energy, health science, space science, biotechnology, big data and education.

However, the UAE is not the only country with groundwater issues, and this technology may be able to assist others struggling with similar concerns. But first, the civil engineers need to pilot their solutions and they are in the process of selecting sites – one to inject water directly into a deep aquifer, and another to create a recreational park and/or a botanical garden. “We prefer, of course, to have an artificial lake that is sustainable, that would attract people to come and visit,” Professor Sherif says.

Read “New system for the assessment of annual groundwater recharge from rainfall in the United Arab Emirates”, published in Environmental Earth Sciences, to find out more about UAEU’s work in ground water research.

Find out more about UAEU.