Lessons learned from building a new university premises

Rick Trainor reflects on the trials and tribulations of constructing a new, multipurpose building from scratch at the University of Oxford

Higher education communities have changed considerably in recent years. In terms of staff and students, institutions are increasingly diverse, and this population has varying preferences but also needs to interact in a variety of ways. Meanwhile, those fulfilling different functions – academics, administrators, other employees, undergraduates, postgraduates, alumni and visitors – are decreasingly content to spend their time in distinct, separate spaces.

Encouraged by ever more digitised ways of working and relaxing, and boosted by post-pandemic changes in how people spend their time, informality and flexibility are the order of the day. Likewise, higher education institutions increasingly desire interaction with their localities and regions – and the world beyond. Meanwhile, virtually all the inhabitants of these institutions are much more environmentally conscious than they were even a few years ago. There is also an increasing appetite for institutions to provide pleasing physical spaces conducive to community – mere functionalism is not enough.

- What should universities think about when redesigning their campuses?

- Creating ‘third spaces’ will revolutionise your campus

- How campus layout influences social ties and research exchange

These changes in higher education institutions and the people who spend time in them have major implications for the buildings at universities and colleges. The typical post-1945 university building, with its rigidly separate spaces for functions such as study, teaching, research, administration and recreation – and its resulting de facto separation of functional groups – is no longer adequate.

Likewise, buildings oblivious of environmental effects, or structures designed in styles alien to local neighbourhoods, are decreasingly acceptable not only to planners but to students and staff. Indeed, the notion of a university building remote from its surrounding community now seems outmoded. Yet higher education, suffering from major resource constraints, often has to make the best use of its existing building stock while periodically building afresh.

These complex considerations confronted Exeter College, the fourth oldest of the University of Oxford’s colleges, in the early 2010s when it faced an acute shortage of space on its physically constrained historic site. Purchase of a property within walking distance provided a possible solution but raised many issues. Discussions within the college quickly established functional priorities – more student accommodation, additional teaching and learning spaces and room for the storage and consultation of the college’s large stock of manuscripts and pre-1800 books.

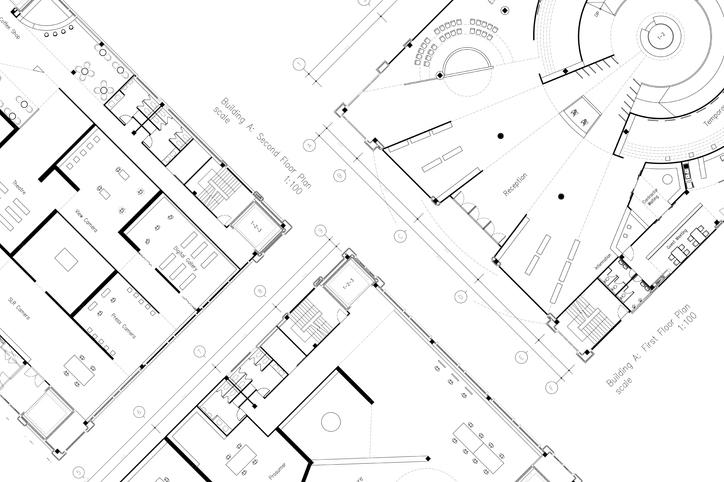

A transcending concept that emerged was that of a “third quadrangle”, combining functions as on the historic site but with the “collegiate ideal” adapted to 21st-century needs. Alison Brooks Architects (ABA), which won the architectural competition, produced an ingenious S-shaped design with many innovative internal features. This held out the promise of meeting Exeter’s practical needs in ways adapted to the changing demands of higher education.

For those contending with a similar predicament, it has become clear that having such a clear vision, and engaging in detailed discussions with architects about how to achieve it, were prerequisite to the eventual, award-winning, multipurpose building (now known as Cohen Quad). Particularly important for inclusivity and informality was opting for a large, central “learning commons” with an adjacent café, and for “family kitchens” within the residential areas, with individual faculty offices and particular support functions located around the periphery of the building.

Meanwhile, self-regulating temperature mechanisms help with sustainability, while a division of labour between the new building and the historic site (reserving the latter for, for example, traditional dining, a formal library and a bar) preserved the coherence of the college as a whole. Similarly useful was the deployment by ABA of both cloister arches and plate glass, thereby blending the old and the new.

But of course there were many crucial intermediate steps, which any HE institution contemplating a major building project will have to negotiate, especially if (as in this case) the site contains an existing building in a densely built-up neighbourhood.

Be prepared for investigations to determine that the inherited building/s cannot be adapted to the vision. In the case of Cohen Quad, the existing building’s multiple levels and staircases conflicted with the college’s inclusive aim of physical access throughout. Our dialogue with local planners also reinforced the historic value of the oldest part (circa 1910) of the existing structure, the façade of which therefore had to be retained.

Also, the site was not large, so architectural ingenuity was required to fit the various functions into the space while preserving the light and outdoor circulation space inherent in the notion of a “quadrangle”. In addition, the sensitivities of neighbours necessitated particular attention to the height and appearance of the design, reinforcing our existing preference that the building incorporate traditional elements.

Also crucial to be aware of, such increasingly complex requirements had implications for the building’s financing, which had to draw on multiple sources. A further challenge – particularly for relatively small institutions with few administrators – is choosing a contractor and interacting frequently with that company, the architects and cost consultants concerning the intricacies of construction.

In retrospect, the project might have been usefully different in some respects. For example, it would have been highly advantageous to avoid the term’s delay in completing the building, which required Exeter to pay for substitute accommodation for affected students. In addition, post-completion practical issues occupied more attention than anticipated.

But at least as important as these cautionary aspects were positive lessons, notably the value of close attention to how a building’s design is implemented in practice. From its opening in 2017, the college and its users have encouraged, in the learning commons and café, the mixing of people performing various functions within the institution, while the family kitchens quickly became centres of socialising as well as cooking and eating.

Likewise, consider informal booking arrangements that allow students to use classrooms outside normal teaching hours for coveted informal group study sessions. We also rapidly opened the space to meetings and conferences, both within the broader University of Oxford and beyond; the wider public’s enthusiastic response to the building’s attractive design and functionality helped break down the barriers that new buildings can sometimes create with their surroundings.

Some of the features of Cohen Quad are, of course, particular to Oxford and its collegiate structure. Yet the project’s overall approach – its inclusive vision, continuing dialogue with architects, blend of tradition and innovation, complementarity to existing buildings, outward orientation, emphasis on sustainability, informality and flexibility – may have relevance to a variety of higher education institutions as they face decisions concerning their physical environment.

Sir Rick Trainor is rector of Exeter College, University of Oxford.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.