Adaptability is different from resilience – and here’s how to nurture it

Disruption has always been part and parcel of life, but there is increasing recognition that the nature and pace of disruption today are unprecedented. Shifts to and from remote learning and work, evolving technology, the rise of artificial intelligence, climate change and periodic surges in Covid-19 are just some of the disruptions making headlines. Then there are the normative life-course changes to navigate, such as starting and finishing school, university or college, beginning working life, moving out of home, changing jobs, marriage/partnership, child-rearing/caregiving and retiring from work.

Adaptability has been identified as a vital attribute for successfully navigating disruption, and our research team has pioneered theory and assessment of adaptability in educational settings. We recently expanded our research programme to investigate adaptability among university students during Covid-19, and in this piece we aim to unpack the concept of adaptability (including how it is different from resilience), share findings from our adaptability research in the university sector and identify practical strategies to boost university students’ adaptability.

The difference between adaptability and resilience/disruption and adversity

Whereas a lot of research has – quite rightly – been focused on understanding how to deal with adversity, far less attention has been given to how to deal with disruption. Researchers have too often confused (a) adversity, threat and challenge with (b) change, novelty and uncertainty. But it’s crucial to remember that not all change is adverse, not all novelty is a threat and not all uncertainty is a challenge. Given this, we emphasise the importance of disentangling adaptability (the attribute for responding to disruption) from resilience (the attribute for responding to adversity).

What is adaptability?

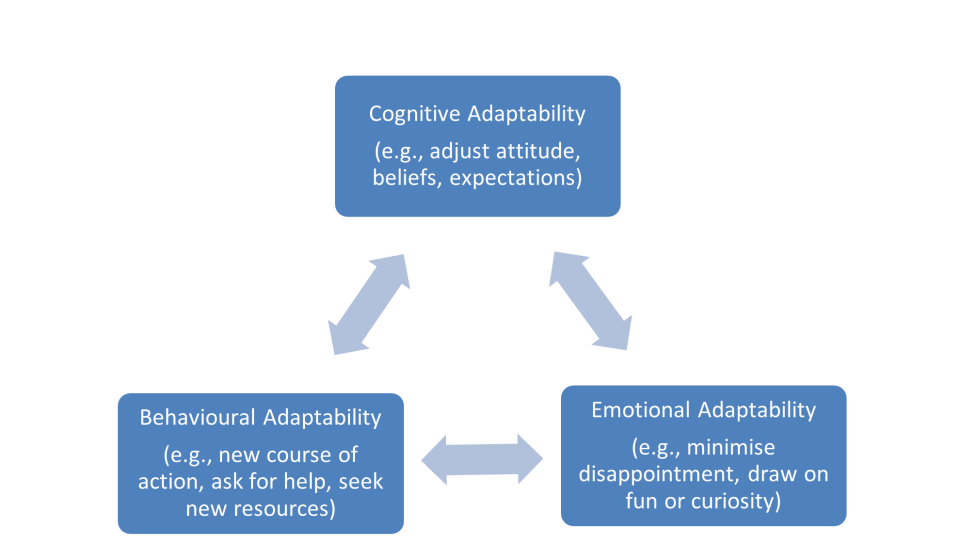

The American Psychological Association defines adaptability as “the capacity to make appropriate responses to changed or changing situations; the ability to modify or adjust one’s behaviour in meeting different circumstances or different people”. We would extend this definition to include not only behavioural regulation but also cognitive and emotional regulation. This is known as the “tripartite” perspective on adaptability.

Cognitive adaptability refers to the capacity to adjust thoughts and thinking to deal with disruption. Behavioural adaptability is the capacity to adjust the nature, level and degree of behaviour or action to successfully navigate disruption. Emotional adaptability refers to the capacity to adjust emotional responses to successfully deal with disruption.

Having defined the components of adaptability, we went on to develop and validate the adaptability scale to assess each of the three dimensions. It is this scale that we have used in our research among university students in the UK, as well as our most recent study of university students in Australia (described below).

Adaptability among university students

This recent study involved a survey of Australian university students to examine, among other things, the role of adaptability in their learning during a period of Covid-19 that entailed mandatory lockdown. A representative sample of 500 full-time undergraduates from 41 Australian universities completed the survey. Of these, 70 per cent of students reported being in mandated lockdown at some time in the two weeks before the survey. Students responded to the adaptability scale, which asked them to rate items on a continuum of one (strongly disagree) to seven (strongly agree) for how much they are able to respond to disruption in their lives (for example, “to assist me in a new situation, I am able to change the way I do things”). They also answered questions about their confidence as learners and their university participation, aspirations, enjoyment and disengagement.

We found that students’ adaptability was significantly associated with higher levels of academic confidence and greater academic participation, aspirations and enjoyment. In fact, these positive effects were found even after controlling for the influence of lockdown, students’ background attributes (such as gender and socio-economic status) and problem-solving ability. We concluded that adaptability is an important factor in how university students navigate learning during Covid-19 and, potentially, other disruptions that may affect learning. We further concluded that because adaptability is modifiable, the research offers fruitful direction for helping students during periods of academic and other disruption.

Boosting adaptability

Here, we suggest two approaches for boosting students’ adaptability. The first approach comes at a general level, where students are taught about the cycle of adaptability. The second is at a more granular level, where students are taught how to adjust specific thoughts, behaviours and emotions in the face of disruption.

At the general level, it can be helpful for students to know about the cycle of adaptability and what they can do in each part of it. This can involve university staff (such as lecturers or counsellors):

- teaching students how to recognise disruption in their life, especially as disruption approaches or occurs in real time (sometimes we can leave it too late before we realise disruption is happening)

- explaining to students the three areas of their life they can adjust: thought, behaviour and emotion (more details are in the granular approach, below)

- encouraging students to adjust one or more of their thoughts, behaviours and emotions in response to disruption

- helping students recognise the benefits of these adjustments when they are made

- helping students continue to apply and refine these adjustments as they navigate future disruption

At the granular level, students are supported by university staff to understand the three adaptability dimensions more deeply – including specific ways they can attend to each facet to navigate disruption.

Cognitive adjustments include:

- thinking about a new or uncertain situation in a different way (for example, encourage students to think about the opportunities that become possible in the new situation)

- adjusting assumptions or expectations during times of transition (for example, encourage students to see the positives in change rather than seeing change as a “bad” thing)

Behavioural adjustments include:

- seeking out new or more information, help or resources to deal with a new situation or activity (such as encouraging students to ask a lecturer for additional reading or websites for a new topic)

- taking a different course of action (talk to students about reorganising their study schedule or study strategy following the announcement of a change in assessment task)

Emotional adjustments include:

- minimising disappointment, fear, frustration or anger when a situation changes (help students minimise disappointment if circumstances mean an enjoyable activity has been cancelled or deferred)

- drawing on or maximising fun, curiosity and enjoyment when circumstances shift (encourage students to focus on the stimulating and engaging aspects of a new task or activity)

Conclusion

In the face of disruptions caused by Covid-19 – and other changes and uncertainties that are part of life – frequent advice has been to adjust to a “new normal”. Our research demonstrates that adaptability is an important personal attribute that can help students make the appropriate adjustments and optimise their academic well-being through university – and beyond.

Andrew J. Martin is scientia professor of educational psychology in the School of Education at UNSW Sydney, Australia.

Paul Ginns is associate professor of educational psychology in the School of Education and Social Work at the University of Sydney, Australia.

Rebecca J. Collie is scientia associate professor of educational psychology in the School of Education at UNSW Sydney.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.