How the idea of ‘excellence’ can be misleading in higher education

You may also like

When is a C good enough?

This question might be a strange one for a top university to ask, but it strikes me as critical. To give it some context, in March the University of California, Irvine hosted the Waypoints Symposium. This meeting brought together representatives from more than 30 institutions to discuss questions in higher education, especially around equity and inclusion. Among the exciting ideas and themes, two stood out to me in particular: the challenge of time for both students and faculty, and the concept of “excellence”.

These themes reminded me of several key learning moments in my career.

The first was when I started working as a faculty member and my father gave me some advice: “It is important to know when good is good enough.” Despite the constant mantra in higher education of “excellence in everything”, it is not possible to be excellent in everything. If you are going to be excellent in some things, you need time. And to have time, you need to let some things be good enough.

- Scales, stars and numbers: the question of evaluation

- Reframing feedback as a valuable learning tool

- Five common misconceptions on writing feedback

Later in my career, this concept was reaffirmed at a leadership training event where we learned about research that showed even the best leaders were excellent in just a few leadership traits and OK in others. This again reinforced the reality that one cannot be excellent in everything.

As I thought more about this question of when good is good enough, I realised that it applies to research really well. Thinking specifically about my own area of experimental physics, it is critical to know the required resolution of any given measurement or design element. If particular parts only need to be accurate to millimetres, it is not worth your time, and is even counterproductive, to get them accurate to nanometres. A common mistake that many young experimentalists make is to strive for maximum accuracy in everything, which usually just ends up as wasted time and effort.

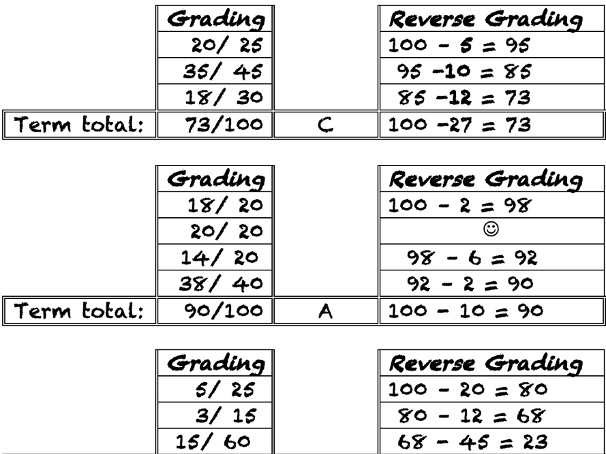

Thinking about the design of experiments helped me to better understand how the idea of “excellence” can be misleading in education. The question I found myself asking applies both to students and faculty: why do we have a range of passing grades (A through C) if we do not seem to take them all seriously? From the student side, it seems safe to assume that students generally want As in their courses, but the reality is that most students do not need As in all their courses. Given this, it seems imperative that faculty embrace Bs and Cs as valid grades.

This means two things: 1) adopting grading approaches that clearly communicate the learning goals that correspond to each grade level (A, B or C); and 2) ensuring our language and presentation support the value of these grades where appropriate.

The first point on communicating learning goals is a critical element of this. Even though I am using the language of “getting a grade”, excellence is really connected with mastery of material or the learning that occurs in the course. The better students understand the level of mastery or learning that each grade corresponds to, the more control they have over their learning outcomes. This really allows them to develop the suite of mastery that meets their needs.

This new perspective on excellence also made me realise that excellence in teaching does not mean “getting an A” in every aspect of our teaching. Just as with experimental design, providing students with an excellent experience in a course does not require every element of the faculty effort to be “A level”. A truly excellent course, as with excellence in leadership, involves excellence in some areas while being good enough in others (assuming there are no holes in the course design).

A challenge with this new perspective on excellence is really understanding and believing that the goal of excellence is rarely to be equally excellent at everything. The challenge is that, for many of us, our undergraduate experience was perhaps the last time we achieved mostly As (and sometimes all As). Certainly, if you look at their transcripts, most of our students are coming from high school with, in effect, all As and perhaps unrealistic expectations in this space.

Taking the time to think about the right mix of As, Bs and Cs that truly meets our expectations of excellence will be a critical exercise moving forward, especially as we consider the other challenge I mentioned at the beginning of this article: time.

Ultimately, we have to understand and embrace the time limitations that both students and faculty face. Having a reasonable and intentional understanding of excellence will help us set more rational goals and standards for our time commitment to teaching as well as our students’ time commitment to individual courses. Absolutely critical in this exercise is that it will not be lowering any standards of excellence. Instead, we will be able to provide better clarity to students as to what those standards are, allow students to choose the balance of As, Bs and Cs that meet their needs, and help faculty maintain their balance of excellence in research and teaching.

Michael Dennin is a professor of physics and astronomy, dean of undergraduate education and vice-provost for teaching and learning at the University of California, Irvine.

This is an edited version of episode 42, “When is a C good enough?”, of Michael Dennin’s blog.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.