Increasing access to higher education for refugees through digital learning

You may also like

With only 5 per cent of 15- to 24-year-old refugees enrolled in tertiary education globally compared with 37 per cent of non-refugee young people, UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) has set a goal “to achieve enrolment of 15 per cent of college-eligible refugees in tertiary or connected higher education” by 2030. This 5 per cent is reflected among refugee students in Lebanon, with persistent barriers including, but not limited to:

- financial destitution

- legal status

- curriculum discrepancies

- lack of psychosocial support and career guidance

- discrimination

- inadequate learning environment.

The rights of refugees to engage in wage-earning employment and labour market integration under the Lebanese law are limited to low-skilled jobs in construction, agriculture and cleaning services. More than 60 per cent of refugee youth are unemployed, according to the latest figures. Their barriers to securing dignified jobs include skills mismatch, lack of documentation, lack of knowledge of social and legal protections, and xenophobic sentiment of host communities. Between 2016 and 2021, the American University of Beirut (AUB)’s Center for Civic Engagement and Community Service collaborated with King’s College London to design and implement a college-readiness programme PADILEIA (Partnership for Digital Learning and Increased Access) to increase the pipeline of refugees towards tertiary education and provide transferable skills for employment.

- Practical ways to develop a comprehensive university ‘sanctuary’ programme

- How universities can support refugee students and academics

- Displaced workers deserve more than short-termism from universities

Despite the complex challenges facing Syrian refugees in Lebanon, 20 per cent of PADILEIA graduates transitioned into higher education. So, achieving 15 per cent of enrolment for refugees globally in tertiary education could be aided enormously by applying the lessons from PADILIEA more widely.

How PADILIEA works

PADILIEA was built around five structural strands:

1. Outreach and recruitment:

Over two months, information about the programme was disseminated using: the UNHCR database; referrals by NGOs, surrounding municipalities and school principals; announcements on social media; and by engaging selected alumni as admissions officers. Eligibility criteria included valid registration with UNHCR, financial need and a threshold of educational attainment. Shortlisted applicants were invited to the PADILEIA campus for placement exams in English and mathematics and assessed for their commitment to the eight-month programme, and a cohort of 60 were selected for the foundation programme each year. Outreach for the Moocs (massive open online courses) took four weeks, and 30 learners, with active email addresses and access to mobile devices, registered for each of the eight courses offered.

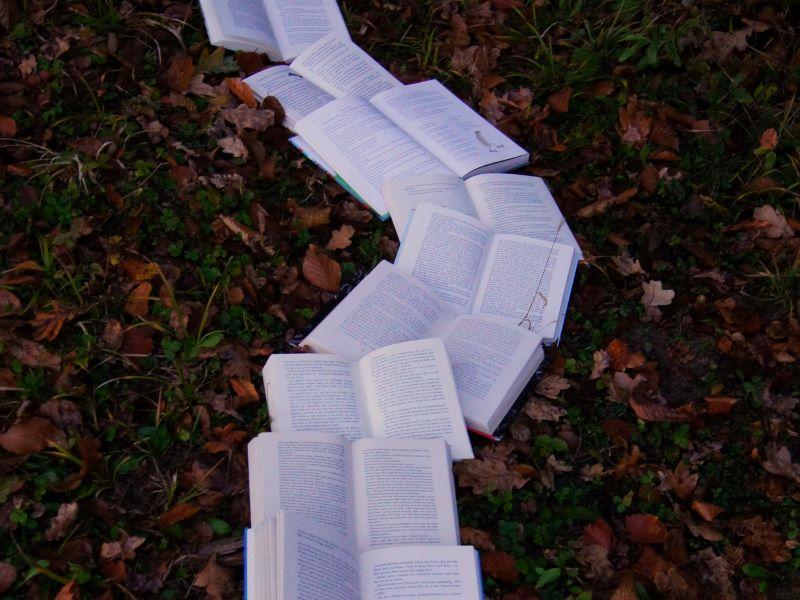

2. PADILEIA portable campus:

Classroom units were assembled by refugees themselves close to where they were staying. The structures are based on AUB’s Ghata model (using the Arabic word for shelter) that has been inspired by refugees’ shelter-building practices. Each unit is 20 square metres, scalable, cost-effective, ecologically responsive and structurally secure, and each one takes two refugees six hours to assemble and three hours to disassemble for relocation. The PADILEIA campus composed of two classrooms, made up of tripled Ghatas of 60 square metres each, an administration unit from a single Ghata, semi-dry sanitation cubicles and an outdoor space.

3. The foundation programme:

Running over two terms and lasting 32 weeks in total, this programme comprises five academic courses: English for academic purposes, digital skills, remedial maths, science, and humanities/social sciences. AUB professors developed the curriculum, revised it and updated it annually, and recruited local instructors and trained them to incorporate student-centred techniques in their teaching. Courses were offered four days per week and on a double-shift schedule (morning and afternoon) to maintain small class sizes that are conducive to project-based learning and which can accommodate students employed in part-time jobs.

4. Facilitated Moocs:

Designed by King’s College London, the online courses focused on topics that would increase student employability in fields in high demand on the local labour market, such as nursing, English language skills, programming, engineering construction and digital skills. Classrooms were equipped with computers and internet access, and two facilitators assisted learners to navigate the requirements of each topic, troubleshoot common issues with online courses, provide academic support and assess weekly progress. Each course averaged four to six weeks, with four to six hours of learning per week.

5. Students support day:

Delivered by career and major orientation advisers, the weekly group sessions addressed topics such as career planning, CV writing, interviewing techniques, and preparation for college and scholarship applications. Group sessions were also conducted by mental health experts who equipped participants with techniques to identify trauma-related disorders and handle mild to moderate referral cases under the supervision of an AUB faculty expert. Referral pathways were established for the diagnosis and treatment of severe cases. In close coordination with UNHCR, individual support was provided by legal experts on protection, documentation and resettlement.

The significant success of this five-year pilot project makes the UNHCR’S bold goal achievable. The 15 per cent enrolment target is dependent upon scaling and contextualising PADILIEA’s five strands, while also developing more advanced programmes that widen the pipeline at secondary education levels.

Rabih Shibli is director of the Center for Civic Engagement and Community Service (CCECS) at the American University of Beirut (AUB) and primary investigator on the PADILEIA project.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.

Additional Links

Find out more about the PADILEIA project on AUB-CCECS website

From crisis to hope: a short video on the PADILEIA project by BBC StoryWorks