Using film to prompt discussion in legal studies

You may also like

Films and TV shows can be invaluable for engaging law students. Most will have limited prior personal experience of legal systems, so these forms of media might initially inform students’ opinions of the law and the legal system. Films and television might also have influenced their desire to study law in the first place.

Of course, the idea of using film as a teaching tool is not new. However, the tendency can be to use films in passing (for example, including science-fiction concepts in jurisprudence modules). Modules that fully embrace these media in their entirety, however, have significant potential to introduce innovative teaching methods, as well as setting elective modules apart from the core curriculum.

Classes that present cases, legislation and legal theories can lead to whole modules being a fact-driven memory exercise. Module leaders are also looking to diversify and decolonise the curriculum, presenting materials that challenge students’ perceptions, develop a contemporary understanding and application of legal principles, and facilitate critical discussion among students.

How film can introduce diverse experiences and cultures

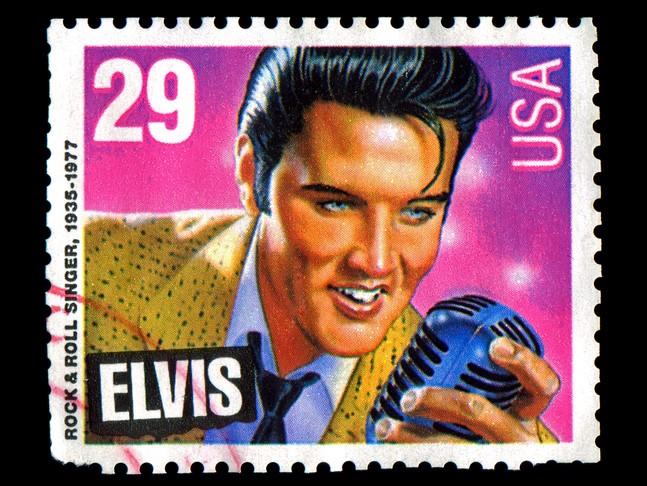

At the Strathclyde Law School, the Law, Film and Popular Culture module uses films to discuss the sociology of law, with a focus on representation of different groups in the legal system and the consequences. Students watch a film before a lecture, with the film providing the theme for discussion – for example, Chicago is used to discuss both negative stereotypes of lawyers and the representation of women in the justice system. This enables students to apply their preconceived legal analysis to a set of given facts and scenarios in an alternative manner.

- How can students learn to be innovative?

- Co-creation as a liberating activity

- Playful learning: how to get started

Such a module can present content that tackles legal issues and critique via a different medium (and so may suit visual learners more than “chalk and talk” lectures, for example). The selection of films can also give an opportunity to include materials that present a wider range of views and legal cultures. World cinema offers a plethora of potential discussions around the interaction between law and culture, as well as representations of the experiences of indigenous, BAME or LGBTQ+ communities, for example, and their interactions and representations in the legal system.

The 2012 film Wadjda tells the story of a 10-year-old girl who enters a Koran recital competition at her school because she wants to use the prize money to buy a bicycle. It is the first feature film entirely shot in Saudi Arabia. This film can be used to challenge students’ perceptions of family units and children’s rights (specifically around education – in form as well as access). Students can then discuss how the law might operate accordingly and reflect on a different legal culture (for example, in definitions of a family).

Classes such as these can reflect the personality of the class coordinator. If, for example, the coordinator has a background in professional advocacy, the selection of materials could focus on cross-examination biases and inaccuracies as a form of training. However, if they have a more theoretical background, they could apply feminist or anti-racism theories to challenge students’ initial thoughts. Furthermore, as students bring their own examples to the discussion, the class coordinator’s own perceptions are challenged.

Challenges in creating film-based legal modules

Challenges remain, though. Although the class coordinator will have their own background and interests, awareness of potential materials and their availability is one part of the equation. Online searches and word of mouth can unearth relevant titles, but a research or personal interest in specific areas might also prove useful. I discovered Wadjda because I am a cycling fan. Finding a book about Arabic cinema in a charity shop brought Moumen Smihi’s 2005 semi-autobiographical film, A Muslim Childhood (El Ayel), to my attention. Set in 1950s Tangier, it is about a young boy’s experience of secular education and could form an interesting comparative discussion with Wadjda and a more Western film.

Once you have identified films you’d like to use, copyright and licensing may also need to be addressed. On the one hand, streaming services mean that more films than ever are accessible to students. Yet it can be difficult to make films available to the class without expecting students to pay for access (while setting a high standard on copyright compliance). For example, A Muslim Childhood is not available on our university’s standard licensing platforms and databases (Kanopy, Box of Broadcasts and Planet eStream). One solution would be to organise an institutional screening; some streaming services allow for educational use (see for example Netflix’s policy) or a physical screening may be possible with certain restrictions.

One of the films we use on the module is the 2018 film The Meeting, an independent production that depicts a restorative justice meeting between the victim of a sexual assault and the perpetrator. It is not available on DVD and the film’s official website directs to renting the film. We contacted the production company and bought a licence for an MP4 version, which can be embedded on the class page.

As a possible long-term solution to these challenges, to complement the Law and Film class, we are introducing a fourth-year honours module called Law in the Context of Contemporary Culture. This will be a seminar-led class, allowing for a greater range of material to be set, while also giving a structure for students and staff to contribute to the discourse. Class coordinators can use examples from music, gaming, art, photography and literature.

Ultimately, film- and culture-based modules present unconventional options for students and staff. In applying legal principles and analysis in contemporary settings, they can build critical discussion and engagement and challenge biases in a way other modules can’t.

Michael Randall is a teaching fellow in the Strathclyde Law School at the University of Strathclyde.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.