‘Using GenAI is easier than asking my supervisor for support’

Doctoral researchers are turning to generative AI to assist in their research. How are they using it, and how can supervisors and candidates have frank discussions about using it responsibly?

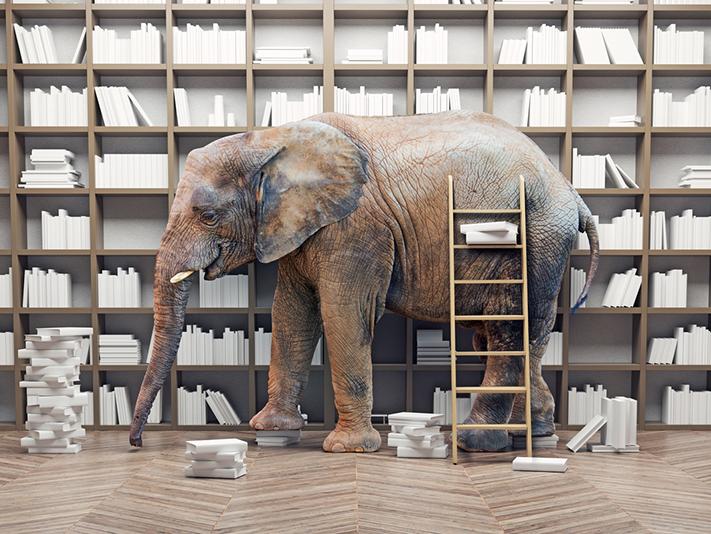

Generative AI is increasingly the proverbial elephant in the supervisory room. As supervisors, you may be concerned about whether your doctoral researchers are using GenAI. It can be a tricky topic to broach, especially when you may not feel confident in understanding the technology yourself.

While the potential impact of GenAI use among undergraduate and postgraduate taught students, especially, is well discussed (and it is increasingly accepted that students and staff need to become “AI literate”), doctoral researchers often slip through the cracks in institutional guidance and policymaking.

Anecdotally, we had heard whispers from doctoral researchers about how they were already using GenAI in their everyday doctoral research – tasks they describe range from assistance with generating research ideas and finding academic literature to editing their writing so it sounds “more academic”. We wanted to find out more.

- Resource collection: AI transformers like ChatGPT are here, so what next?

- Spotlight guide: Advice for surviving your PhD dissertation

- Campus podcast: the pros and cons of AI in higher education

So, we asked postgraduate researchers about why and how they use GenAI in research. Our survey of doctoral researchers at institutions across the UK was designed to give us a sense of their perceptions and uptake of these rapidly burgeoning technologies. In addition, we sought to more thoroughly understand how doctoral researchers articulated boundaries of (un)acceptable usage.

We received 75 responses to our survey from researchers at 19 institutions. It was a small sample, undoubtedly, but their responses provided insights into the role(s) and (dis)advantages of using GenAI in doctoral research. Several key findings, we believe, will be of significance to doctoral supervisors, as well as to those working in doctoral professional development more broadly.

Like it or (maybe) not, many doctoral researchers are using GenAI in their research, writing and assessment

More than half (52 per cent) of respondents had used GenAI within their doctoral research and/or writing, with ChatGPT being overwhelmingly the tool of choice. Some PGRs had included AI-generated text in their doctoral writing (12 per cent) and assessment (9 per cent), all without having declared they had done so (a finding that may realise supervisors’ fears).

‘If trained properly, it can be used for any purpose’: GenAI as a valuable tool or a ‘human-like’ colleague that can help speed up research progress

While the above data suggests at least some cause for concern when it comes to issues of plagiarism and originality, qualitative responses to our survey revealed a more nuanced and interesting picture about how doctoral researchers were using GenAI. Some viewed it as an exciting and advanced tool to aid in their doctoral research – for example, to test or improve code, much like any other technology that has come before it. Additionally, some viewed it as a more human-like colleague and even co-supervisor from whom they could get a second opinion or editorial support (especially those who use English as a second language).

‘A rather stupid but always available brainstorming partner’: doctoral researchers’ use of GenAI is not unequivocal

Despite some doctoral researchers’ excitement about the possibilities of GenAI, many were concerned about the acceptable usage and its limits within doctoral research. They outlined concerns about the ethics (and responsible use) of GenAI, data security and the potential for bias inherent in the data underpinning algorithms to be repeated in its outputs. Of note for supervisors, given the importance of originality to a doctorate, were concerns around how far doctoral researchers could use GenAI in their work (and for what tasks) before it compromised their ability to claim it as their own.

‘All PhD students should be supported in their engagement with AI just as they would be supported with other tools’: implications for supervisory practice

That GenAI platforms offer attractive shortcuts and perceived sounding boards to help the doctoral researcher has important implications for supervisors. As the role of supervisor is to help the development of the researcher as much as the research, this must now include guidance on the responsible use of AI.

The ethical aspects of the technology along with questions of plagiarism and attribution are obviously important. However, more nuanced questions also arise, which vary among disciplines. We call for doctoral supervisors to reflect on the following questions: what tasks are we happy for a PGR to outsource to an AI platform and which are essential for a researcher to learn by doing? Is asking an AI program to summarise a dense academic article a convenient shortcut or is it outsourcing the researcher’s judgement as to what are the important or interesting parts of a study? How may AI outputs bleed biases and assumptions into research outputs and what impact may the use of those outputs have on original thinking?

In addition to considering the above, we argue that supervisors and doctoral researchers must have open and frank discussions about use of GenAI from day one of candidature. These conversations could include discussions about the following: how doctoral researchers have used GenAI in previous studies or professional roles; institutional policies and guidance on GenAI to establish boundaries of acceptable use; the benefits and drawbacks of GenAI for different research tasks, and how the doctoral researcher should disclose use of GenAI in their work when submitted to the supervisor for feedback.

Being able to discuss the above with the doctoral researcher may require AI-upskilling of your own. As this technology becomes ubiquitous and effective in producing reliable responses, the possibility of more doctoral researchers viewing it as an alternative online colleague or supervisor grows. For supervisors, to ask and understand how their doctoral researchers are using the technology is the first step towards helping guide them in the responsible use of GenAI.

Ross English and Rebecca Nash are senior teaching fellows, and Heather Mackenzie is a principal teaching fellow, all at the University of Southampton.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Comments (2)

or in order to add a comment