A (very) simple solution to cheating

I teach at a university in Hong Kong and have just received the final exam timetable for this semester. It is a stark reminder that I need to start crafting the exam papers and thinking of ways to minimise cheating.

I recall an interesting conversation with a colleague who has decades of teaching experience. He viewed cheating as one of life’s necessary evils. In his words: “If all the top minds from the most prestigious institutions were not able to eliminate this problem over the past many centuries, maybe it’s more meaningful to find a way to embrace it.”

This conversation got me interested enough to look up the history of cheating. From a simple search on Google Scholar, I found an article by Andy Kuo of Stanford University, entitled A (very) brief history of cheating, in which he wrote, “In the history of mankind, for as long as there have been social structures, there have been cheaters.”

- Online exams are growing in popularity: how can they be fair and robust?

- Democratic assessment: why, what, and how

- Assessment design that supports authentic learning (and discourages cheating)

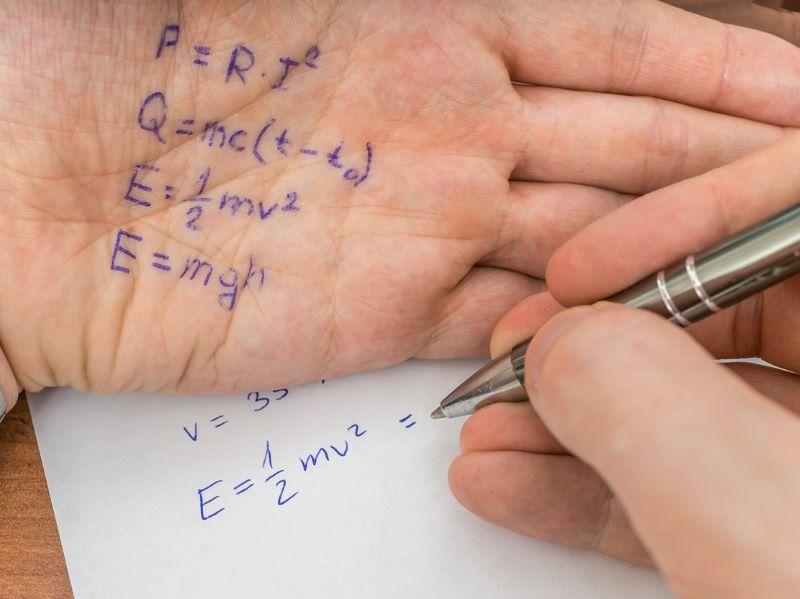

I thought back to the days when I was a student. Although I was never involved in attempts to cheat, I witnessed all kinds of commonly used cheating techniques, which included smuggling notes into exam venues and having information written on water bottles, pens and even on the inside of jackets. Fast forward to today, these traditional techniques are still commonly used. It is therefore not a surprise to see exam policies stipulating what items can or cannot be carried into the venue. With new technology, students are now using mobile phones to cheat, so the list simply got longer to include all electronic devices. The problem of academic dishonesty, however, never went away.

“Legalise” cheating to encourage deeper study

Instead of trying to achieve the mission impossible, my colleague suggested a very simple change to the exam policy: to “legalise” cheating, but in a regulated manner. His “legalised cheating” idea is simple: allow students to bring one sheet of prepared notes into the exam venue.

This is not the same as an open-book exam. If students know that they can bring all their textbooks, teaching notes and reference papers into the exam, the tendency is to rely on these materials instead of spending time reviewing the critical content as part of their exam preparation. This mentality may sometimes be counterproductive given the pressure of multiple exams towards the end of the semester. However, if they are only allowed to bring one sheet of paper, there is a good chance they will make an effort to produce their own unique “cheat sheet” with as much key information on it as possible. This is exactly the kind of outcome we as teachers are looking for – active participation in exam preparation.

As module leaders, we have the authority to make changes to exam policies that will facilitate study.

Encouraging honesty in online exams

Until last semester, students were able to come back to campus for in-person exams. This semester, students will be completing exams online. Even regulated “legalised” cheating becomes a challenge when the exam venue is the students’ home, or wherever they may be, with zero invigilation. The use of online proctoring has been widely discussed, as the technology can reduce academic misconduct using webcams and other tools, studies show. However, online proctoring technology also raises ethical concerns. Hundreds of thousands of students from multiple institutions across the world have signed petitions against the use of automated proctoring tools. Their main concern is that their personal privacy is being violated.

My institution, Hang Seng University of Hong Kong, has opted to not use remote proctoring services, unless it is a requirement from the industry governing body. I welcome this approach because current students are already stressed from dealing with the challenges of the pandemic. Remote proctoring simply creates an additional layer of anxiety. In lieu of such technology, my colleagues and I are doing our best in promulgating the importance of academic honesty through personal appeals and storytelling.

In online exams, the most common way to cheat is through ghostwriting. I admit that it can be difficult to detect if the ghostwriter is careful in imitating the student’s use of language and is not too ambitious in trying to achieve a top mark.

What I explain to all students is that ghostwriting is a business aimed at making money. The ghostwriters carry no risk – they are not subject to any punishment or penalty from the university. But students who engage their services and pay them are taking on a huge risk. Three key concerns are:

- They do not know whether the ghostwriter is good enough to achieve a high grade in the exam.

- They do not know whether the ghostwriter’s submission will raise red flags through online portals such as VeriGuide or Turnitin leading to severe consequences for the student.

- There is nothing to prevent the ghostwriter from blackmailing the student for additional compensation in the future.

In the last lecture of any module, I always include the following quote as an appeal to students to refrain from engaging ghostwriters for exams or assignments.

“Even if your cheating attempt is successful in getting you a good grade without being detected, you are never at ease for the rest of your life because you know someone out there is holding evidence and it can be used against you anytime in the future. It is not worth the risk. Not even close!”

Roy Ying is a senior lecturer in the Department of Marketing at the Hang Seng University of Hong Kong.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.