Which specific Covid disruptions impacted motivation and engagement?

Swathes of university and college students the world over have been impacted by Covid-19 and the disruptions associated with it, including lockdown, isolation/quarantine, remote learning and hybrid learning. Although the World Health Organization (WHO) has advised that Covid no longer constitutes a public health emergency, it also recognised that the global assessment risk remains high, with Covid-19 and its variants continuing well into the foreseeable future. This being the case, it is important for educators to know what specific Covid-related disruptions have been impacting different aspects of students’ academic lives. Knowing this, educators are in a better position to support students when these disruptions occur.

Covid-related disruptions to student experience

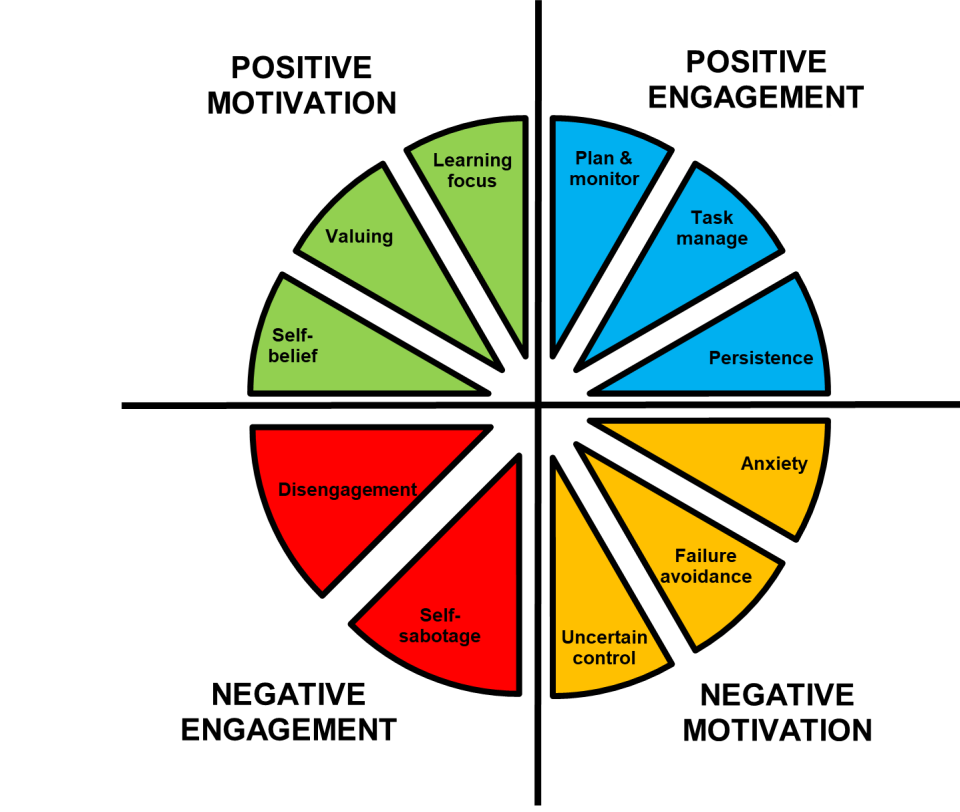

In a recent study, 500 university students in Australia were surveyed about the various Covid-related disruptions they were experiencing at the time of the survey (mid-pandemic in 2022) – including whether they were in mandated lockdown, mandated isolation/quarantine, in fully remote learning mode or in hybrid learning mode. In the survey, they also completed the motivation and engagement scale (MES), a self-report tool assessing each part of the motivation and engagement wheel (see picture below). In addition, the study compared the motivation and engagement of students in this mid-pandemic sample with the motivation and engagement of pre-pandemic university samples that had also completed the MES.

- Spotlight guide: Soft skills for hard times

- Resource collection: The post-pandemic university: how to serve the Covid generation

- The power of failure: a case study to foster resilience in students

Key parts of motivation and engagement assessed in the study

As the figure below shows, the motivation and engagement wheel has four overarching themes, each comprising specific motivation and engagement facets: positive motivation (self-belief, valuing, learning focus); negative motivation (anxiety, failure avoidance, uncertain control); positive engagement (planning and monitoring, task management, persistence); negative engagement (self-sabotage, disengagement).

What did the research show?

The first major finding was that compared with pre-pandemic university samples, the study’s mid-pandemic sample scored significantly lower on positive motivation and engagement factors and significantly higher on negative motivation and engagement factors. Moreover, of all the factors in the wheel, the greatest differences were on the negative engagement factors (self-sabotage and disengagement), with the study’s mid-pandemic sample scoring much higher on these than the pre-pandemic samples.

The second major finding was that being in lockdown or isolation/quarantine was uniquely associated with higher self-sabotage and higher disengagement. That is, over and above any influence of isolation/quarantine and remote/hybrid learning, lockdown was associated with problematic engagement. Meanwhile, over and above any influence of lockdown and remote/hybrid learning, isolation/quarantine was also associated with problematic engagement.

Notably, after controlling for the influence of lockdown and isolation/quarantine, remote and hybrid learning were not significantly associated with university students’ motivation and engagement. It can thus be concluded that lockdown and isolation/quarantine (but not remote or hybrid learning) seemed to be linked to problematic engagement among university students.

So, what does this mean in practice?

Although mandated lockdown and isolation/quarantine are now seen as somewhat historical, the reality is that many students do still stay at home if they, those they live with, or their instructors have Covid-19. It is also the case that the virus continues to mutate, and we do not know what variants (and associated mandated responses to them) lie ahead. It is therefore important to know what aspects of students’ academic lives are impacted in such cases. This study found that the factors most affected seemed to be self-sabotage and disengagement – and so it is these factors that could be targeted by practitioners to assist students through Covid-19 and any other similar disruptions.

How can practitioners help?

Self-sabotage occurs when students place obstacles in their path to academic success. Typical obstacles include procrastination, getting distracted, wasting time, “goofing off” the night before an exam, etc. Disengagement takes this a step further such that students give up, detach or withdraw their participation from some or all of their university activities and tasks. Research suggests that a fear of failure underpins both of these problematic engagement patterns. Fear of failure triggers self-protective behaviour such as self-sabotage (where students use the obstacle as an excuse for their poor performance) or disengagement (where students self-protect by abandoning the race altogether). It seems there is something about lockdown and isolation/quarantine that instil academic apprehension along these lines.

To reduce fear of failure, it can be helpful for students to develop constructive and courageous views of mistakes. For example, educators can make it clear to students that poor performance or mistakes provide important information about how to improve. When students are not so fearful of making mistakes or performing poorly, they are less inclined to adopt problematic and self-protective engagement strategies.

On a related note, educators might also look to better frame students’ perceptions of success so that success is seen as more accessible and achievable. For example, defining success as topping the class limits a student’s access to success (only one student can top the class) and can trigger problematic motivational dynamics, including self-sabotage and disengagement. On the other hand, seeing success more in terms of personal improvement gives all students access to success (as all students can strive to improve in some way) and reduces the inclination towards problematic failure dynamics in the forms of self-sabotage and disengagement.

Another reason students may self-sabotage or disengage is because they feel little or no control over how well they do at university. This uncertainty elevates their fear of failure, which can prompt an inclination towards self-protection strategies such as self-sabotage and disengagement. To help with this, educators can direct students’ attention to three parts of their academic lives that they do control: effort (how hard they try); strategy (the way they try); and attitude (what they think about themselves, their instructor, etc).

To sum up

There are Covid-19 disruptions that have affected major aspects of university students’ engagement. Pinpointing these helps educators better understand the educational landscape that students have had to navigate these past few years – and what disruptions and engagement factors to be attentive to going forward.

Andrew J. Martin is Scientia professor and professor of educational psychology in the School of Education at the University of New South Wales, Australia.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.