White privilege doesn’t exist for working-class men in higher education

In 2004, when I first arrived on campus, almost immediately I noticed a lack of working-class students like me. The giveaway was the lack of Yorkshire accents or, indeed, many regional accents at all. This came as a surprise to me because I had travelled just 12 miles from my home in the Calder Valley, an area popularised by Sally Wainwright’s Happy Valley.

As my time at the University of Leeds went on, almost everyone I met seemed to be from privileged backgrounds. Some had parents who owned businesses, some enjoyed rowing, others spoke fondly about their time at Cheltenham Ladies’ College and other private schools. None had grown up in a single-parent household and waited in a bank after school while their mother cleaned it. That experience was all mine.

Imposters

Fast forward 20 years and I’m back at the University of Leeds. But this time I’m a lecturer teaching the subject that I studied two decades earlier. After a successful corporate career as a human capital consultant, I had hoped mine was the kind of social mobility success story that would now be commonplace. Except it isn’t. In fact, the opposite is true. Examples of working-class students seem even harder to identify than before.

White privilege?

The notion of “white privilege” is lazily tossed around within higher education. But this crude term of reference is extremely problematic. While there are, of course, white people who enjoy considerable privileges, there are many, many more who benefit from none, but who nonetheless find themselves incorrectly labelled.

The reality of “white privilege" for working-class students is that it doesn’t exist. “White working class pupils have been badly let down by decades of neglect and muddled policy thinking,” concluded a report by the Education Committee in 2021, with its chair, Robert Halfon, adding: “We also desperately need to move away from dealing with racial disparity by using divisive concepts like white privilege that pits one group against another.” A report by King’s College London went further, concluding that “white working class boys with good school grades are still less likely to progress to higher education than their high-attaining peers from other ethnic groups and social classes” and that “the problem is more pronounced in elite institutions, where barriers exist at both application and admission”.

Something is going badly wrong. There are also potentially serious consequences. The Financial Times rightly stated that “teaching poor white kids about ‘white privilege’ might be at best inappropriate, and at worst stoke resentment.”

Lack of action

The obstacles faced by white working-class men at elite universities are nothing new. But the rate of progress in relation to this issue remains painfully slow. The underlying consideration, of course, relates first and foremost to social class. There is also a clear reluctance among elite universities to acknowledge the issue and take assertive actions to address it. It is hardly the behaviour of organisations that claim to promote meaningful commitments to equity, diversity and inclusion.

There is, however, some cause for optimism. The University of Bradford recently announced the launch of scholarships for white working-class males. It identified that just 1.7 per cent of its students were white working-class males versus an equally pitiful 4.6 per cent average across the higher education sector. The inaction of elite universities is concerning.

- Resources on equity, diversity and inclusion in higher education

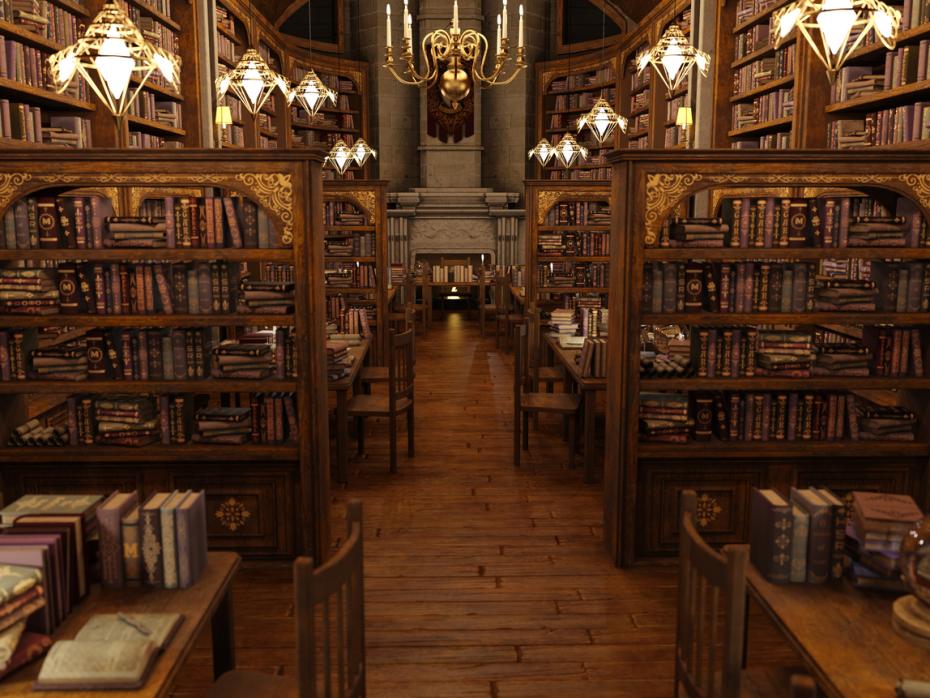

- Building a university library service where everyone feels welcome

- How to embed inclusion into the curriculum

The forgotten ‘ism’: classism

Elite universities urgently need to start focusing their diversity and inclusion activities on social class, with a clear focus on white, working-class men in particular. Social class must be considered a protected characteristic. An abundance of socio-economic data can be used to support this, including data in relation to household wealth provided by the Office for National Statistics.

Target setting

Universities need to work with the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa) to set clear targets for the recruitment of white working-class men. Positive action must be taken to ensure that university populations reflect wider society.

Financial barriers

Support must include grants to help with rising living costs, yet another barrier for white working-class males. Many elite universities are cash-rich and have large endowments, so money is therefore not the problem. The issue is whether leaders have an appetite to use it in a way that drives change.

Universities, particularly those in the Russell Group, need to offer meaningful funding to white working-class men to encourage them to apply and study. My own postgraduate course cost about £3,000 when I completed it in 2004. It now costs in excess of £15,000. For international students, this rises to more than £30,000. That’s before even factoring in living expenses. The inevitable outcome is that rather than education driving social mobility, the diametric opposite is now true.

Role models

Universities must also provide relatable examples of role models who demonstrate what can be achieved by white working-class men with the right support and encouragement. At the University of Leeds, we have Prime Minister Keir Starmer as a compelling example of how effective education can drive social mobility. But we need many more. Without them, and without putting the above strategies in action, elite universities cannot in good conscience say that they are delivering a core purpose of their social mission.

Mark Butterick is lecturer in human resource management and management consulting at the University of Leeds.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.