The world’s research universities are incredible engines of discovery and innovation. Yet as the world’s problems grow ever more complex, interconnected and urgent, academic researchers won’t be able to solve them alone.

Challenges such as climate change, food insecurity and the rapid emergence of AI demand that universities reach beyond their own walls and engage in new levels of collaboration with more varied and even unexpected partners.

At Vanderbilt, the research university in Nashville, Tennessee that I oversee, we have built a culture of what we call radical collaboration – a way of working in which problem-solvers readily partner with experts outside their disciplines, silos and sectors to bring a richer mix of capabilities and viewpoints to bear on challenges and arrive at solutions faster. This week, we showcased this approach at Times Higher Education’s World Academic Summit in Manchester because we believe radical collaboration can create new possibilities around the world.

Universities have long partnered with corporations. But these partnerships can be slow-going or episodic. And even when they’re working together, universities and companies often miss areas of overlap that can be rich with mutual opportunity.

At Vanderbilt, we’ve worked closely with corporate partners to develop what we call the “Collaboration Accelerator” model. It begins with a half-day meeting designed to get experts from our university and our partner organisation in the same room – researchers, innovators, practitioners, even top leaders – to learn about one another’s work, to brainstorm and to identify opportunities for working together.

Project management and other structures then support teams as they work together towards their objectives. Regular showcase events highlight successful projects and foster new opportunities for collaboration, keeping the cycle going.

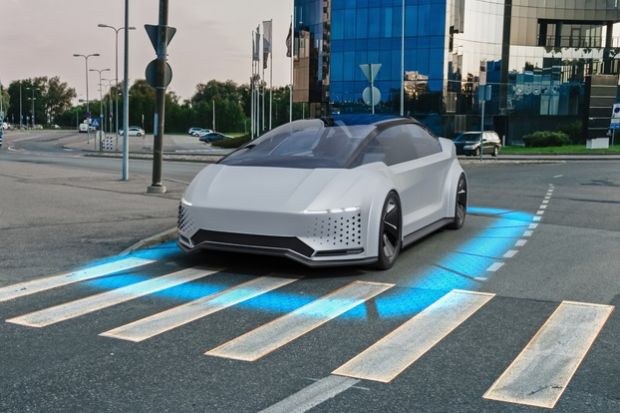

It’s an approach that cuts through barriers, builds trust and leads to results. With our partners at Nissan Americas, for example, we’ve embarked on more than a dozen research and business-optimisation projects, encompassing AI and autonomous vehicles, charging and electrification, product development, finance and more. With tyre-maker Bridgestone Americas, we’ve identified opportunities to jointly advance mobility innovation and sustainability – and that partnership is just getting started.

Of course, collaboration should not be restricted to the private sector. Universities also have a long history of working with local governments to improve communities. We recently joined Nashville’s mayor in launching the Nashville Innovation Alliance, which brings together public, private, civic and education institutions to enhance the region’s innovation ecosystem – the sectors of the economy driven by technology and entrepreneurship – and to ensure the city remains economically competitive, with prosperity that includes everyone.

To that end, we’ve worked with our partners to hold an Innovation Ecosystem Forum, where developers of innovation districts from several global cities shared their experience in creating innovation districts. And the Alliance will soon launch its Urban Innovation Lab, which will leverage the expertise of local institutions to deploy solutions addressing some of the city’s most pressing challenges.

Radical collaboration isn’t an either/or proposition – partnering with either business or government. It invites as many perspectives as possible, especially for significant, multidimensional challenges.

Vanderbilt recently worked with the Tennessee Department of Transportation to implement a unique, real-time traffic “testbed” on a four-mile stretch of local highway. Then we collaborated with a large consortium of automakers, federal agencies and other universities to test, with 100 specially equipped vehicles in peak-hour traffic, an AI-powered cruise control system designed to increase fuel savings and ease congestion. The result was some of the most important mobility research done to date – only made possible by the mix of minds, capabilities and resources at the table.

Academic collaboration isn’t new. More than a decade ago, for instance, the host of the World Academic Summit, the University of Manchester, began a partnership with EDF focused on clean energy, innovation and nurturing future talent. The University of Warwick is working with Jaguar Land Rover and Tata Motors to develop the cars of tomorrow. And, famously, the University of Oxford successfully collaborated with AstraZeneca to research, create and manufacture a Covid-19 vaccine.

But as the recent Labour Party conference repeatedly heard, there is a clear need for greater innovation in the UK, as elsewhere. The chancellor, Rachel Reeves, spoke of “potential held back” at the UK’s “world-leading universities, creative industries, life sciences, tech companies and professional services”. And Peter Kyle, secretary of state for science, innovation and technology, said that his party’s “number one mission is to be the partner scientists need to tackle disease, climate change and economic growth”, from AI and life sciences to addressing digital exclusion to widening full-fibre internet connectivity.

This calls for deeper and more radical collaboration between universities, governments, business and the rest of civil society. The benefits go both ways. Companies, governments and other partners gain new insights without the full costs and risks of undertaking the research themselves. They also get a ready pipeline of qualified potential employees in university graduates.

University researchers, in turn, can increase the impact of their discoveries and innovations by accessing real-world problems and data. And they can facilitate the commercialisation of new products and services based on basic research, bringing needed solutions to scale.

The challenges facing humanity won’t be met by people isolated in ivory towers or research labs, cubicles or conference rooms. We need more cooperation, ideation and inspiration across boundaries real and imagined. Only such radical collaboration will deliver the solutions our world so urgently needs.

Daniel Diermeier is chancellor of Vanderbilt University.