Next week, the Office for Students will become fully operational, taking over in April from the Higher Education Funding Council for England. But what do we really know about this new all-powerful regulator?

So far, the OfS has consisted of little more than its board and the appointments process has already been heavily criticised over political interference by Downing Street.

As Lord Stevenson prophetically remarked in the Lords’ debates of January 2017, it is “one thing to have a series of representations and an equitable and appropriate way of appointing people, but quite another to be clear that this is done in practice”.

But let us assume for the moment that this body of 15 people, with its one student representative, is now competent to do the job in hand.

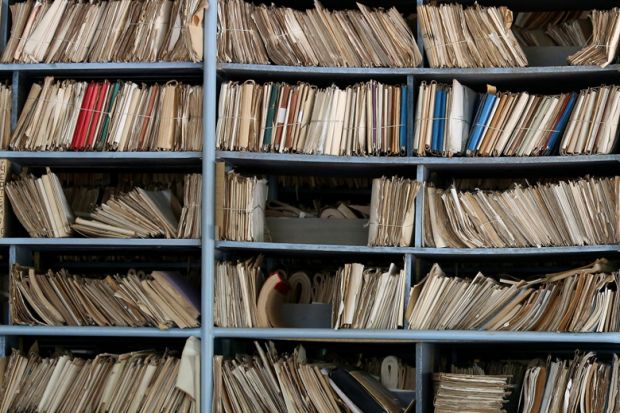

From April, when the OfS is fully in charge, it will start putting into action its plans, which were uploaded to its website at the end of February. In addition to a 166-page regulatory framework, there were about two dozen other lengthy documents made available.

But what exactly is the status of all these documents dumped on an impatient English higher education sector by the Office for Students? Call me a nerd but the question niggles.

For instance, one of them explains how the regulatory framework is being “presented to Parliament pursuant to section 75 of the Higher Education and Research Act 2017”. But this is a process that needs careful watching.

“Drafting infelicities in relation to statutory instruments, the use of Henry VIII powers and similar matters” were all pointed out by peers during the act’s second reading.

“Under the bill, the OfS will be, for practical purposes, beyond Parliament’s reach” were some of the strong words from the Lords’ debates. The Delegated Powers Committee also declared concerns about statutory instruments to be made under the act.

In one sitting, Lord Lisvane described the proposed OfS authority over the powers to grant degrees as “Henry VIII [powers] on stilts” in the debates about the act. “I do not believe it is acceptable to delegate to the OfS such significant law-making powers in the sector which it is to regulate,” he said.

There is also the question of what to make of the section headed “ministerial guidance” in the online document dump.

This includes a letter of “strategic guidance”, which it seems is the OfS-era counterpart of the annual grant letter that Hefce used to receive, which identified the block grant of public funding.

This letter was signed by Sam Gyimah, the universities minister, and not the secretary of state as the grant letter was. It includes, however, a similar listing of “priorities” and “strategic guidance”.

Below this, in the dump, is listed more guidance from the Department for Education, including guidance for the OfS on the granting of degree-awarding powers and university title. However, the OfS is supposed to produce its own “detailed guidance” for applicant providers.

“We would like the OfS to conduct a review of the operation of the effectiveness of the reformed system for applying for, and obtaining DAPs, at an appropriate point after at least three years of operation,” the guidance explains.

So, that will be self-review by the OfS, reporting on its own work to the DfE?

And which parts of all this, if any, could constitute statutory instruments? They are not made by the secretary of state or by Parliament. Are they just quasi-legislation? Who knows?

According to its framework, when wrestling with complexities in the validation of other providers by holders of degree-awarding powers, the OfS may “make use of its powers under section 50 of HERA to enter into commissioning arrangements. It may also ask the secretary of state to make regulations under section 51 of HERA to authorise the OfS to enter into validation agreements with registered higher education providers itself”.

So, the OfS would not go to the minister but to the secretary of state to make these “regulations”? And would Parliament see that the OfS was getting its own degree-awarding powers?

In addition, there is no agenda or minutes of the OfS board, so we do not know their views on these issues. However, the published OfS governance arrangements note that the board is to act “within the limits of its delegated authority agreed with” the DfE. I think that we should be told more about that.

We need much more clarity about the status of all these rules and documents huddling under the Higher Education and Research Act.

Gill R. Evans is emeritus professor of medieval theology and intellectual history at the University of Cambridge.

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?