Automata – self-moving mechanical figures – come to us from a deep past. Plato and Aristotle described cunningly designed artefacts that mimicked the movements of human bodies. Like us, yet not like us, a well-crafted automaton can dance and sing, smoke a pipe or play a musical instrument. In the 18th century, there were androids so technologically accomplished that they could defeat human opponents in games of chess, draw pictures and handwrite thought-provoking little notes stating: “I think therefore I am.” There were even automata that defecated and engaged in sexual acts. The chess player was a fraud – a very smart, very small human was wedged inside. The defecating duck, however, really did excrete from internal bowels. Less is known about the copulating automata, as none seems to have survived. (We can imagine them melting in the fires of Victorian furnaces.) Indeed, there is something about the automaton – a lively thing that is always already dead – that makes it both potent and vulnerable. Goethe saw the decrepit featherless remains of the no-longer-defecating-duck in 1805 and wittily observed that it had lost its powers and was “utterly paralyzed”.

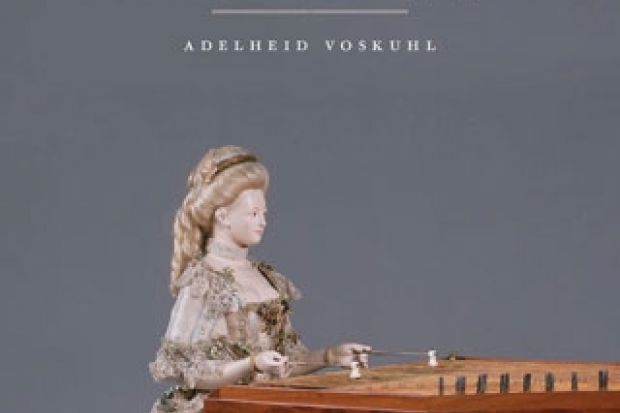

But just what were the powers of automata? They have long moved at the edges of artistic and scientific practices, but their historical functions have proved difficult to pin down. It is tempting to situate them as anxiety-provoking ancestors of the cyborg and the computer, harbingers of artificial life, artificial intelligence and human/machine amalgams such as the factory production line. But automata are more elusive than this. They rarely move along expected trajectories, but tend to dart off in other directions. Plato, at least, saw them in this way, writing: “If no one ties them down, they run away and escape. If you have one untethered, it gives you the slip like a runaway slave.” It is the slipperiness of automata – especially their refusal to be tied to predictable historical narratives – that Adelheid Voskuhl confronts in Androids in the Enlightenment. Squarely addressing the question of the automaton’s powers, Voskuhl examines the production and reception of two keyboard-playing female androids. She forcefully argues that these works disrupt assumptions about the android’s potential to arouse fears about the animated machine.

In an effort to strip the automaton of its harbinger status, the book seems to start from the advice of René Descartes, who claimed that when the automaton is exposed as a work of human devising, it loses its strange powers. Combing through details of economic conditions, business and workshop practices, mechanical designs and printed textual descriptions, Voskuhl finds no evidence of fear. This occurs later, she argues, and the final part of the book turns to modern literary sources that do frame automata as uncanny threats to the human. This line of the argument, which circles the absence of historical evidence, risks delineating a void, and at times it seemed to me that the androids themselves gave us the slip by disappearing into it. Chapter titles register this slippage: “The harpsichord-playing android; or, clock-making in Switzerland” and “The dulcimer-playing android; or furniture-making in Rhineland” are mainly about what comes after the “or”. But androids do differ significantly from finely crafted clocks and furniture. At the heart of the book, the argument takes a fresh turn and demonstrates how the expressiveness of music-making androids aroused the sentiments of their 18th-century audiences. Instead of turning humans into unfeeling machines, these affectless machines stirred human passions. Ultimately, this is why the automaton matters: it has the power to make people feel, and in so doing, to think – whether with fear, pleasure or uncertainty – about what it means to be alive.

Androids in the Enlightenment: Mechanics, Artisans, and Cultures of the Self

By Adelheid Voskuhl

University of Chicago Press, 296pp, £31.50

ISBN 97802260340 and 34331 (e-book)

Published 8 July 2013