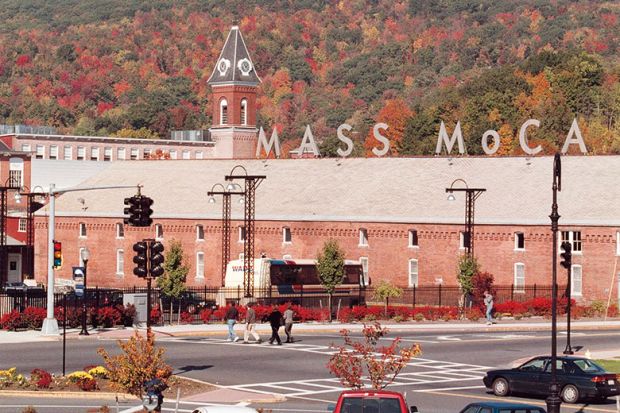

In 2007, the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art sued the Swiss artist Christoph Büchel over an artwork it had commissioned from him. Training Ground for Democracy was an installation protesting against the Iraq War. Representing a war-torn city, it occupied a gallery the size of a football pitch. The museum had spent several months and $300,000 in accumulating the materials Büchel required – such as a tank, nine shipping containers and a replica of Saddam Hussein’s “spider hole” – but the Boeing 727 fuselage he insisted on proved unobtainable. Büchel therefore declared the exhibit unfinished, refusing either to complete it or to remove its components and reimburse the museum. He countersued (several members of the public had seen the provisional exhibit without his permission), although he eventually withdrew the suit.

This case inspired K. E. Gover – philosophy professor and art critic at Bennington College, Vermont – to ask in what sense an artist owns their artwork and when this ownership ends. Not after the work has left the artist’s hands (in Büchel’s case it had never been in them). As Gover says, an artwork is more than a material object: it has and expresses “immaterial, intellectual content”. Unlike other artefacts, artworks cannot (under the 1990 American Visual Artists Rights Act) be intentionally altered, painted or destroyed. Does the artist, then, continue to own the work even after having sold it? “A poem is never finished, merely abandoned,” said the French poet Paul Valéry. This is not just rhetoric. Walt Whitman kept altering Leaves of Grass until he died. Anthony Caro repainted a sculpture he had sold, Steel Painted Orange, first in another shade of orange, then in blue. But surely an artist is not entitled to tinker with their work indefinitely?

In thinking about art, we operate with an odd mixture of intuition, precedent and theory, says Gover. The importance of artworks’ individual authorship, which only began in the Renaissance, was intensified by the Romantics’ view of there being “a kind of primal emotional and spiritual identification between the artist and work”, such that harm to the work constitutes harm to the artist. Gover rebuts this “emotivist” account of artistic authorship – and also the “responsibility” alternative, which emphasises the artist’s intended meaning, rather than the material outcome of it. She proposes a “dual-intention theory”, which “entails two moments of intention” – the artist’s initial intention and their ratification of the work as theirs.

Surely, this is unworkable, too. The processes of intending and ratifying each take more than a “moment” – and the problems of ascertaining when they occur and how they are to be identified persist.

Better at stirring up questions than at answering them, Gover is at her most interesting when discussing the paradoxes of “appropriation art”. Could Richard Prince rightfully claim that, by adding a guitar and crude colouring to photographic images “appropriated” from Patrick Cariou, he had transformed them into new works with new meanings? Could he consistently invoke “artistic freedom” to condone both his “appropriating” and his exclusive ownership of the result? As Gover points out, postmodern jargon about the death of the author – and proclamations about artists’ need to épater la bourgeoisie – are contradicted in practice, as artists clamour for their rights and their payment.

Jane O’Grady is a co-founder of the London School of Philosophy and taught philosophy of psychology at City, University of London.

Art and Authority: Moral Rights and Meaning in Contemporary Visual Art

By K. E. Gover

Oxford University Press, 208pp, £40.00

ISBN 9780198768692

Published 8 April 2018

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?